Few mysteries from the ancient world have captured the human imagination quite like that of the Lost Tribes of Israel. Rooted in biblical history and carried forward by centuries of legend, folklore, and scholarship, their story is at once historical, spiritual, and deeply human. Who were these tribes? Where did they go? And can archaeology—the science of uncovering humanity’s past—help us find them?

The tale begins nearly three thousand years ago, in the fractured kingdom of ancient Israel. It is a story shaped by conquest and exile, by the collapse of empires and the persistence of faith. The disappearance of these tribes has left behind an alluring enigma: one part historical record, one part theological question, and one part archaeological treasure hunt. To trace their story is to walk the boundary between myth and evidence, between scripture and soil.

The Biblical Backdrop

The narrative of the tribes is anchored in the Hebrew Bible. After the death of King Solomon around 930 BCE, his united kingdom split into two: the southern kingdom of Judah, ruled from Jerusalem, and the northern kingdom of Israel, centered around Samaria.

The northern kingdom was home to ten of the twelve tribes of Israel—Reuben, Simeon, Dan, Naphtali, Gad, Asher, Issachar, Zebulun, Ephraim, and Manasseh. Judah and Benjamin remained in the south, preserving the Davidic line and the city of Jerusalem as their center.

The fate of the northern kingdom would prove disastrous. In 722 BCE, the Assyrian Empire swept through the land, conquering Samaria after a brutal siege. Biblical texts such as 2 Kings describe the aftermath: the Israelites of the north were deported, scattered throughout the Assyrian territories, and strangers were resettled in their place. From this moment, the ten tribes effectively vanish from history.

Exile or Assimilation?

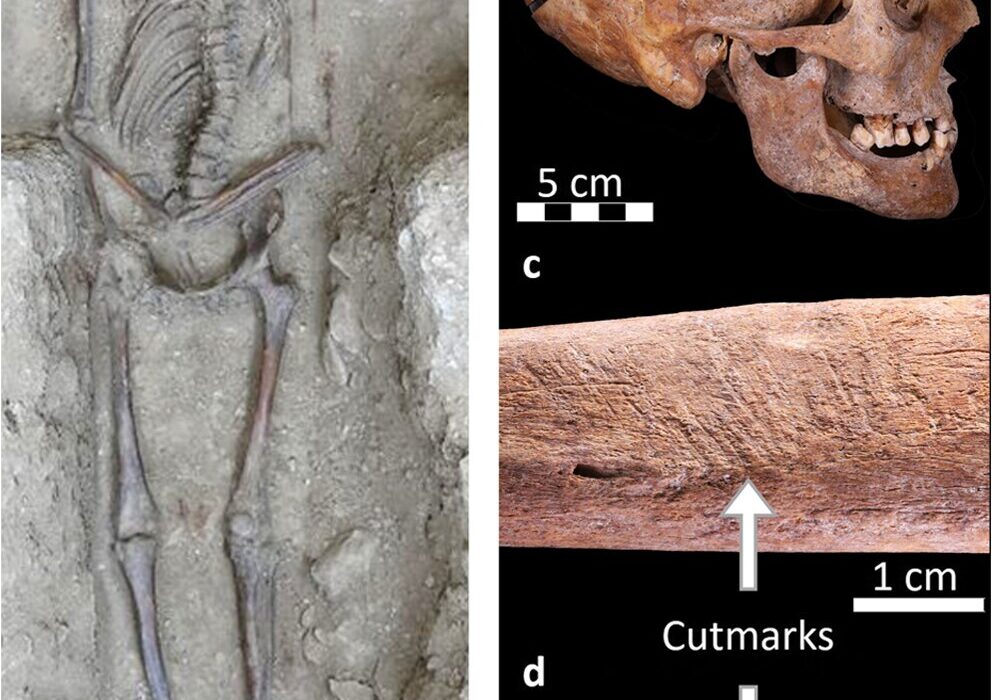

The Assyrian policy of forced deportation was not unique to Israel. To prevent rebellion, Assyria uprooted conquered populations, dispersing them across its vast empire, from Mesopotamia to the fringes of Persia. Archaeological evidence supports this policy: inscriptions, stelae, and administrative records detail the relocations of entire peoples.

But what of the Israelites? Did they vanish entirely, or were they absorbed into the societies around them? This question has shaped centuries of debate. Archaeology suggests a spectrum of outcomes. Some Israelites likely remained in the land, assimilating with incoming populations. Others may have been resettled in regions like Media and Assyria, slowly merging into local cultures. The complete “loss” may be more a matter of memory than of disappearance.

Traces in Assyrian Records

One of the most tangible places where archaeology meets the story of the Lost Tribes is in the records of the Assyrian kings themselves. Assyrian annals, inscribed in cuneiform on clay tablets and monumental inscriptions, boast of victories over Israel.

The annals of Sargon II, for example, describe the conquest of Samaria in 722 BCE, stating that 27,290 inhabitants were deported. While not explicitly listing the tribes by name, the figures confirm the scale of the upheaval. Reliefs from Assyrian palaces depict deported peoples, their belongings piled onto carts, driven away under guard. Such images may well represent the Israelites among countless other displaced groups.

Archaeologists working in sites like Nineveh and Nimrud have uncovered administrative texts mentioning deportees from “the land of Omri” (a biblical term for Israel), placing Israelites firmly within the empire’s machinery. These records provide some of the strongest evidence that the tribes did not vanish overnight but became threads woven into the Assyrian fabric.

The Archaeology of Samaria

Back in the land of Israel, the ruins of Samaria tell their own story. Excavations at the capital city reveal layers of destruction consistent with the Assyrian conquest. Beneath the rubble, archaeologists have uncovered luxurious palaces, ivory carvings, and inscriptions, evidence of a wealthy and cosmopolitan society before its fall.

What followed was a patchwork of settlement. Archaeological surveys in the northern hill country suggest continuity of population, with some villages persisting long after the Assyrian invasion. Pottery styles and building remains hint that not all inhabitants were deported. Some Israelites may have survived in small, rural communities, their identities eventually blending with incoming peoples such as the Samaritans.

The Samaritans: Heirs of a Lost Kingdom?

The Samaritans, a community that still exists today, may preserve part of the story of the Lost Tribes. They claim descent from the tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh, who remained in the land after the Assyrian conquest. Their holy mountain is not Jerusalem’s Zion but Mount Gerizim, near ancient Shechem.

Archaeological findings in Samaria—such as inscriptions, ritual structures, and distinctive religious artifacts—support the deep roots of Samaritan identity in the northern kingdom. While biblical writers often portrayed Samaritans as outsiders or heretics, archaeology suggests that they represent a continuity of Israelite tradition, perhaps preserving voices of the very tribes thought “lost.”

Echoes Across the Ancient World

The disappearance of the tribes did not prevent their memory from traveling far and wide. Over centuries, legends of the Lost Tribes spread across the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and Europe. Different peoples claimed descent from them, weaving the mystery into local identities.

Archaeology occasionally intersects with these claims. In Afghanistan and Pakistan, for example, some Pashtun tribes have oral traditions linking them to the Israelites. While material evidence is scarce and controversial, linguistic hints and genetic studies have fueled speculation.

In Ethiopia, the Beta Israel community—sometimes called the “Falasha”—claims descent from the tribe of Dan. Archaeological remains of their long presence in Ethiopia, along with genetic evidence, affirm their ancient roots, though whether they truly descend from the Lost Tribes remains unresolved.

In India, the Bene Israel and Bnei Menashe communities tell similar stories of descent, supported by traditions of unique rituals and prayers resembling ancient Israelite practices. Archaeological traces are minimal, but their existence testifies to the enduring pull of the Lost Tribes narrative.

Archaeology and DNA

Modern science has added new tools to the search. Genetic studies, though often contentious, provide glimpses into ancient population movements. Analyses of Jewish and Samaritan populations reveal complex patterns, showing connections across the Middle East while also confirming centuries of intermixing.

Yet DNA cannot definitively “prove” descent from the Lost Tribes. The passage of nearly three millennia, combined with migration, assimilation, and conversion, has blurred genetic lines beyond certainty. What genetics can do, however, is highlight shared ancestry among communities and suggest possible links to ancient Israelite populations.

Between Myth and Evidence

One of the greatest challenges in tracing the Lost Tribes lies in balancing archaeology with myth. For centuries, the absence of the tribes fueled imagination. Medieval travelers claimed to have found them in Arabia, Central Asia, even beyond the legendary river Sambatyon, said to rage six days a week and rest only on the Sabbath.

Archaeology tempers these legends with evidence. There is no indication of a hidden Israelite kingdom preserved intact somewhere beyond the horizon. Instead, archaeology points toward dispersion, assimilation, and transformation. The tribes did not vanish but changed, their identities merging into others even as memory preserved them as “lost.”

The Persistence of Memory

The archaeological record tells us that while the tribes may not exist as distinct groups today, their legacy persists. Artifacts from Assyrian palaces remind us of their exile. Ruins in Samaria whisper of their once-prosperous kingdom. Samaritan traditions preserve echoes of their worship. And across continents, scattered communities hold fast to the idea of descent from them.

The persistence of the Lost Tribes narrative is itself a testament to human longing—for roots, for identity, for connection across time. Even as archaeology reframes the story, it cannot extinguish its power. The tribes may be “lost” historically, but symbolically, they remain profoundly present.

Why the Mystery Endures

Why does the story of the Lost Tribes captivate us so deeply? Perhaps because it resonates with universal themes: exile and homecoming, loss and survival, memory and identity. The image of entire tribes swept away by empire, scattered across the world, speaks to the fragility of cultures—and to their resilience.

Archaeology offers pieces of the puzzle, grounding the story in clay tablets, ruined cities, and enduring traditions. But the complete picture remains out of reach, as much about faith and imagination as about fact.

Conclusion: The Lost and the Found

The Lost Tribes of Israel are both a historical mystery and a living legend. Archaeology cannot resurrect them in their original form, but it can trace their footsteps through time. It shows us the Assyrian empire’s machinery of exile, the survival of northern communities, the persistence of Samaritan traditions, and the echoes of Israelite identity across distant lands.

In the end, perhaps the tribes were never truly lost. Their descendants live on in ways that are complex, fragmented, and transformed. Their memory endures in sacred texts, in archaeological ruins, and in the identities of people across the globe who see themselves as heirs to that ancient story.

The search for the Lost Tribes is not only about uncovering the past but also about how we, as human beings, connect with history, with myth, and with one another. Through archaeology, the silence of centuries begins to speak—not with a single answer, but with a chorus of possibilities.