Ancient Egypt is often remembered for its towering pyramids, golden treasures, and enigmatic hieroglyphs. Yet, hidden within its history is a less glamorous but equally profound achievement: medicine. The Egyptians lived in a world where survival depended on balancing human frailty against an often unforgiving environment. Death was a constant presence—lurking in disease, childbirth, accidents, and war. And yet, rather than surrender to fate, the Egyptians developed a medical tradition that was astonishingly advanced for its time.

To study ancient Egyptian medicine is to witness a civilization grappling with the mysteries of the body with both science and spirituality. Their physicians were not only healers but also priests, combining practical remedies with religious incantations. What emerges is a fascinating portrait of a people centuries ahead of their time, pioneering medical practices that would echo across millennia.

The Dual Nature of Egyptian Healing

Egyptian medicine was built on a dual foundation: the scientific and the spiritual. On one hand, physicians recognized the physical causes of illness—injury, diet, infections, or environmental exposure. On the other, they saw disease as a manifestation of supernatural forces, curses, or displeased gods. This blending of rational observation with mystical belief may seem contradictory, but it allowed Egyptian medicine to flourish.

For practical ailments, like broken bones or infections, treatment leaned on empirical knowledge. For mysterious or chronic conditions, ritual and magic stepped in. The key is that Egyptians did not see a contradiction. To them, the gods and the body were deeply intertwined, and true healing addressed both realms.

The Medical Papyruses: Windows Into Ancient Knowledge

Much of what we know about Egyptian medicine comes from medical papyri—texts written on sheets of papyrus that served as both reference manuals and teaching tools for physicians. Among the most famous are:

- The Edwin Smith Papyrus (c. 1600 BCE, possibly based on older texts): The oldest known surgical treatise, remarkable for its rational approach. It describes diagnoses, prognoses, and treatments for trauma and injuries without invoking magic.

- The Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BCE): A massive compilation of remedies, covering diseases of the heart, digestive system, skin, eyes, and more. It also includes magical incantations, reflecting the dual approach of Egyptian medicine.

- The Kahun Gynecological Papyrus (c. 1800 BCE): Focused on women’s health, fertility, contraception, and pregnancy. It provides unique insights into how Egyptians viewed reproduction.

- The Hearst Papyrus and the London Medical Papyrus: Containing further remedies for ailments ranging from headaches to burns.

These papyri reveal not just treatments but also a system of reasoning: observe symptoms, offer a diagnosis, then prescribe a therapy. In many ways, they foreshadow modern clinical practice.

Physicians and Specialists: A Structured Medical Profession

Medicine in ancient Egypt was not an informal craft—it was an organized profession, respected and institutionalized. Physicians were often highly trained, and some specialized in particular areas of the body.

The Greeks, who admired Egyptian medicine, recorded that Egyptian physicians were divided into specialists: some focused on the eyes, others on the stomach, teeth, or head. There were even physicians for “diseases of women” and others dedicated to surgery. This early form of specialization stands out as a hallmark of Egyptian medical sophistication.

The most famous physician was Imhotep (c. 2600 BCE), a polymath who served under Pharaoh Djoser. Imhotep was later deified as a god of healing and wisdom, revered for centuries after his death. His legacy illustrates how medicine was not just a practical skill but also a pathway to divinity and cultural immortality.

Anatomy and the Art of Observation

The practice of mummification, central to Egyptian religion, inadvertently advanced anatomical knowledge. Embalmers frequently handled bodies, removing organs and preparing them for the afterlife. Though their focus was religious, the exposure to internal anatomy gave Egyptian physicians a familiarity with organs and tissues.

The Edwin Smith Papyrus demonstrates detailed knowledge of the human body. It describes injuries to the skull, spine, and chest with striking accuracy. It even distinguishes between symptoms that could be treated and those that were beyond help. For example, if a patient could move their limbs after a head injury, there was hope; if paralysis followed, the prognosis was grim.

While Egyptians lacked the advanced tools of dissection later used in Greek and Roman medicine, their careful observation of injuries—especially in soldiers—built a practical understanding of anatomy unmatched in the ancient world.

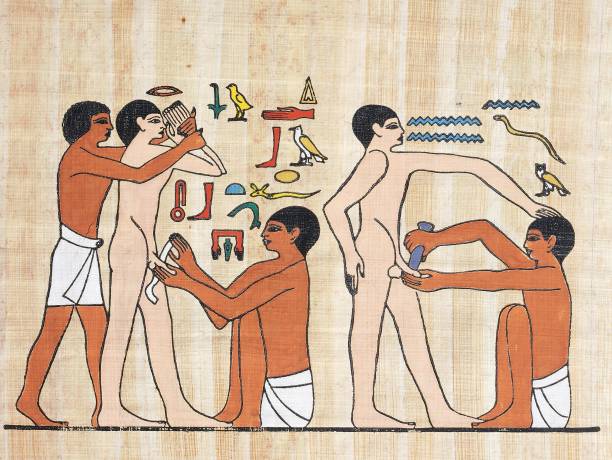

Surgery and Trauma Care

Egyptian surgeons were pioneers of trauma care. The Edwin Smith Papyrus contains dozens of case studies detailing wounds, fractures, and dislocations. Treatments included cleaning wounds with honey (a natural antiseptic), stitching cuts with linen thread, and immobilizing fractures with splints made from wood or reeds.

There is evidence of successful amputations, trepanation (drilling into the skull), and wound dressings using fresh meat to stop bleeding. Bandaging was a carefully developed skill, aided by Egypt’s expertise in linen production.

Importantly, Egyptian surgery emphasized not only intervention but also prognosis. Physicians were trained to distinguish between cases that could be treated, cases that should be monitored, and cases where death was inevitable. This pragmatic classification shows a remarkable degree of medical reasoning.

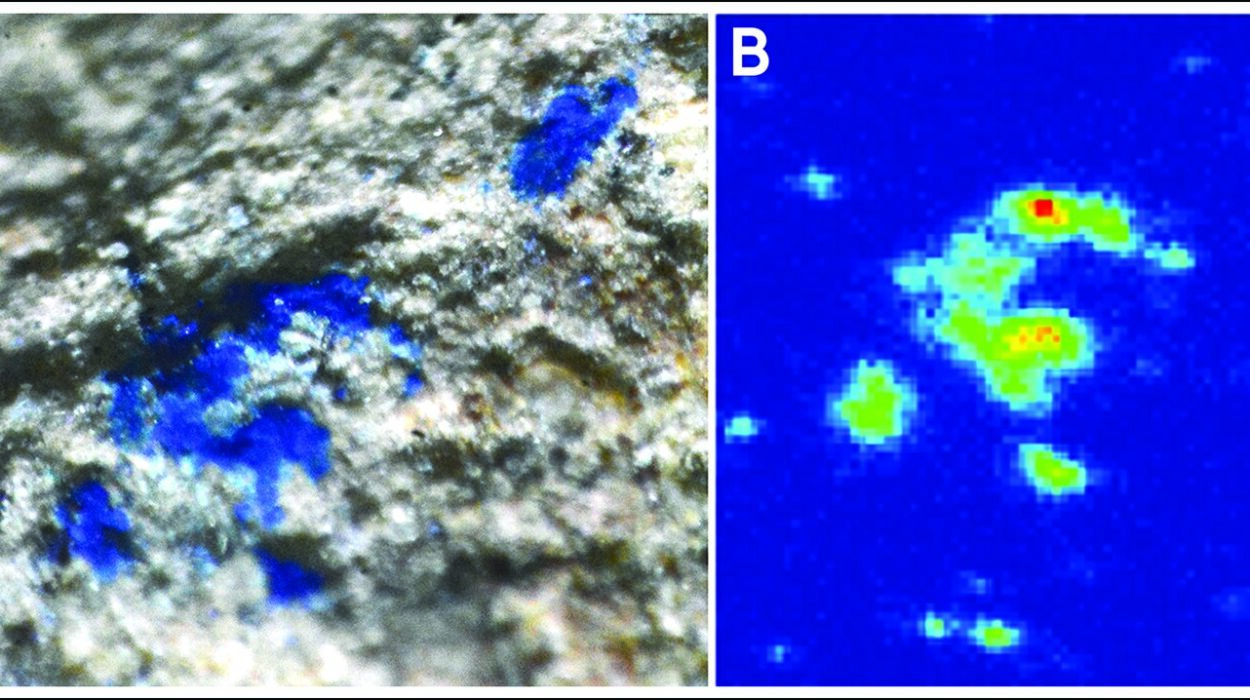

Medicines, Herbs, and Natural Remedies

The Nile Valley provided a rich pharmacy of plants, minerals, and animal products that formed the basis of Egyptian medicine. The Ebers Papyrus lists hundreds of remedies, many of which had real therapeutic value.

- Honey was widely used for wounds due to its antibacterial properties.

- Garlic and onions were prescribed for heart health and general vitality.

- Willow bark, containing salicin (a precursor to aspirin), was used for pain relief.

- Aloe vera treated burns and skin conditions.

- Castor oil served as a laxative.

- Pomegranate was employed to expel intestinal worms.

- Frankincense and myrrh, beyond their religious roles, had antiseptic and anti-inflammatory uses.

Some remedies sound bizarre today—like placing crocodile dung as a form of contraception—but many reflect empirical trial and error, with successes preserved and passed down.

Women’s Health and Gynecology

Egyptian medicine paid particular attention to women’s health. The Kahun Papyrus demonstrates an advanced understanding of fertility, contraception, and pregnancy. Diagnostic methods included examining cervical mucus and using specific herbal treatments to address menstrual or fertility issues.

Egyptian women used pessaries made from honey, natron, and plant fibers as contraceptives—an early attempt at birth control. Pregnancy tests were based on observing germination patterns of grains after being exposed to a woman’s urine. Modern tests on this method show some accuracy, as hormonal changes in pregnancy can affect seed growth.

Childbirth, often perilous in the ancient world, was supported by midwives and magical rituals to protect mother and child. Though maternal mortality was high, Egyptian medicine demonstrates a proactive concern for women’s reproductive health.

Dentistry: The Struggle Against the Nile Diet

The Egyptian diet, rich in bread made from stone-ground flour, wore down teeth to a severe degree. Sand and grit from milling stones caused dental erosion, abscesses, and infections. Mummies often reveal teeth worn to the gums, with evidence of chronic pain.

Egyptian dentists attempted to fill cavities with resin, honey, or ground barley mixtures. Some mummies show crude dental bridges and tooth replacements, though it is debated whether these were done in life or as part of burial rituals. Regardless, dentistry in Egypt highlights an awareness of oral health centuries before many other cultures developed it.

Disease and Public Health

Living by the Nile provided Egyptians with fertile land but also exposed them to disease. Malaria, tuberculosis, schistosomiasis (a parasitic disease from snails in the Nile), and intestinal worms were common. Mummies often show evidence of these conditions.

Egyptian medicine sought both to treat symptoms and to prevent disease. Cleanliness was highly valued, with frequent bathing and the use of natron (a natural salt) for hygiene. Diet, too, was considered central to health. Beer and bread formed staples, but fruits, vegetables, and fish supplemented nutrition.

Priests of Sekhmet, the lion-headed goddess of plague and healing, often served as guardians of public health, tasked with preventing epidemics through both ritual and practical measures.

Magic and Medicine: A Necessary Union

Despite their practical achievements, Egyptians never abandoned the role of magic in healing. Disease was often attributed to malevolent spirits, curses, or the wrath of gods. Spells, amulets, and rituals accompanied medical treatment, providing psychological comfort and cultural meaning.

For example, a physician might prescribe both a herbal ointment and an incantation to drive away the demon believed to cause the illness. Far from undermining the medicine, these rituals strengthened its perceived effectiveness. In a society where religion and daily life were inseparable, magic was as essential as herbs or scalpels.

Legacy and Influence on Later Civilizations

Egyptian medicine did not vanish with the fall of the pharaohs. Its knowledge flowed into Greek, Roman, and Islamic medicine. Hippocrates, the so-called “Father of Medicine,” is believed to have studied Egyptian practices. The Greeks admired the specialization and systematic approach of Egyptian physicians, and many remedies were adopted into their own medical texts.

Even centuries later, medieval scholars in the Islamic world translated Egyptian medical works, preserving them for the Renaissance and beyond. The echoes of Egyptian wisdom can still be traced in modern medicine: in antiseptics, contraception, surgery, and the idea of medical specialization.

The Humanity in Ancient Medicine

What makes Egyptian medicine so compelling is not just its technical achievements but its humanity. These were people who cared deeply about alleviating suffering, who tried to ease pain, heal wounds, and protect mothers and children. They did so with the tools they had: plants from the Nile, honey from bees, linen bandages, and words of power spoken in the name of gods.

Behind every papyrus and every mummified body lies a story of human resilience. A soldier with a broken leg set in splints, a woman tested for pregnancy with grains, a farmer soothed with garlic and honey—these are not just medical cases, but glimpses of lives lived thousands of years ago.

Conclusion: Centuries Ahead of Their Time

Ancient Egyptian medicine was not perfect. It was interwoven with superstition and limited by the absence of germ theory, advanced anatomy, or modern technology. Yet, judged within its historical context, it was extraordinary. Egyptians developed systematic diagnoses, specialized physicians, surgical techniques, and pharmacological remedies that were unmatched in their era.

They treated the body as both sacred and scientific, blending magic with observation in a way that reflects the complexity of human understanding. Their legacy is not just in the medical texts they left behind, but in the enduring reminder that the quest to heal is as old as humanity itself.

To walk through the dusty ruins of Egypt is to see temples, tombs, and monuments. But just as important, though less visible, is the unseen legacy of Egyptian medicine—their passion for preserving life, their determination to ease suffering, and their recognition that in caring for one another, they were touching the divine.