For centuries, Neanderthals were portrayed as primitive beings—strong but dim, survivors rather than thinkers. Yet, in recent years, that image has been crumbling. Each new discovery reveals that these close cousins of modern humans were far more sophisticated than once believed. The latest revelation comes from an unlikely source: fragments of ochre, a reddish-yellow mineral pigment, used not merely for practical tasks, but for art and meaning.

The Color of Ancient Intelligence

Ochre has long been part of human history. This iron-rich mineral pigment was used by many ancient peoples to decorate, dye, and even preserve. Early humans used it for cave paintings, body art, and burial rituals. But now, scientists have found that Neanderthals—long before Homo sapiens reached Europe—were also using ochre in ways that suggest creativity, symbolism, and perhaps even spirituality.

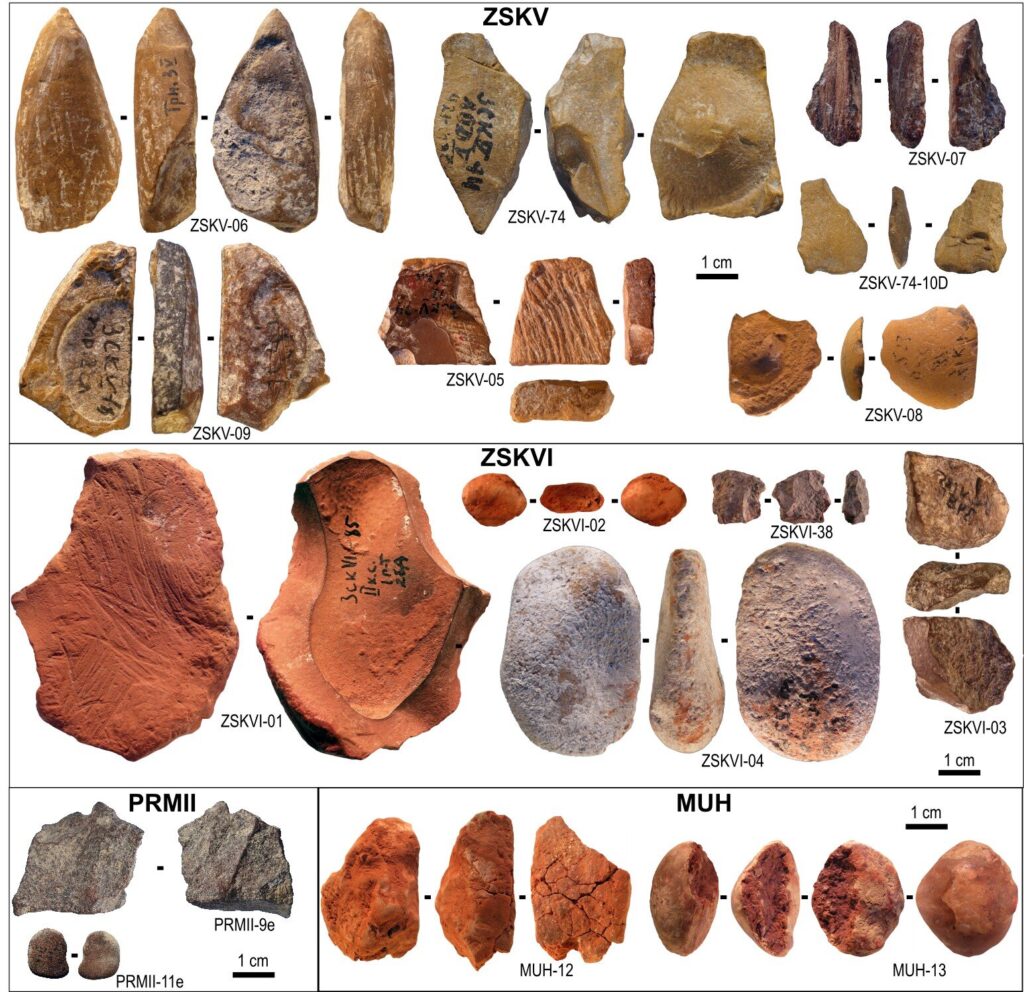

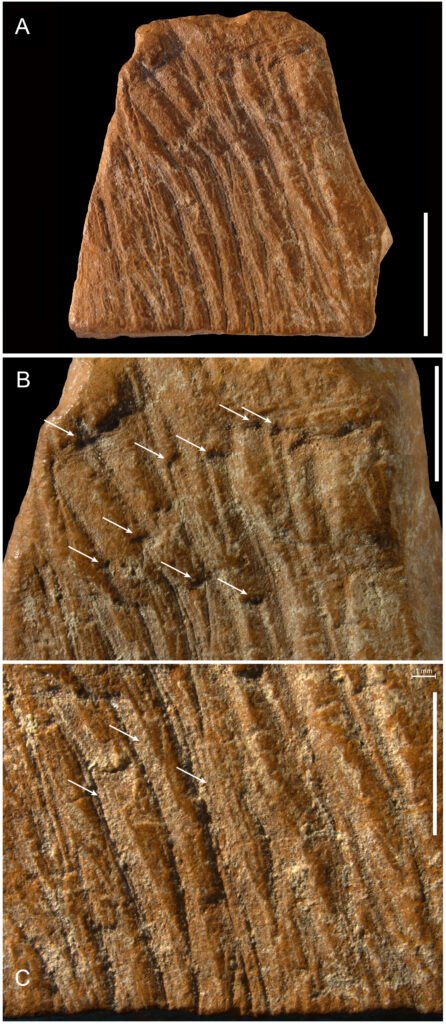

At several Neanderthal sites across Crimea and Ukraine, researchers uncovered small pieces of ochre, some as old as 70,000 years. At first glance, these fragments might seem unremarkable. But a closer look has changed everything. Using advanced tools like scanning electron microscopes and portable X-ray scanners, Francesco d’Errico of the University of Bordeaux and his team have uncovered signs that Neanderthals deliberately shaped and reused these pigments as tools for marking and drawing.

A Crayon from the Ice Age

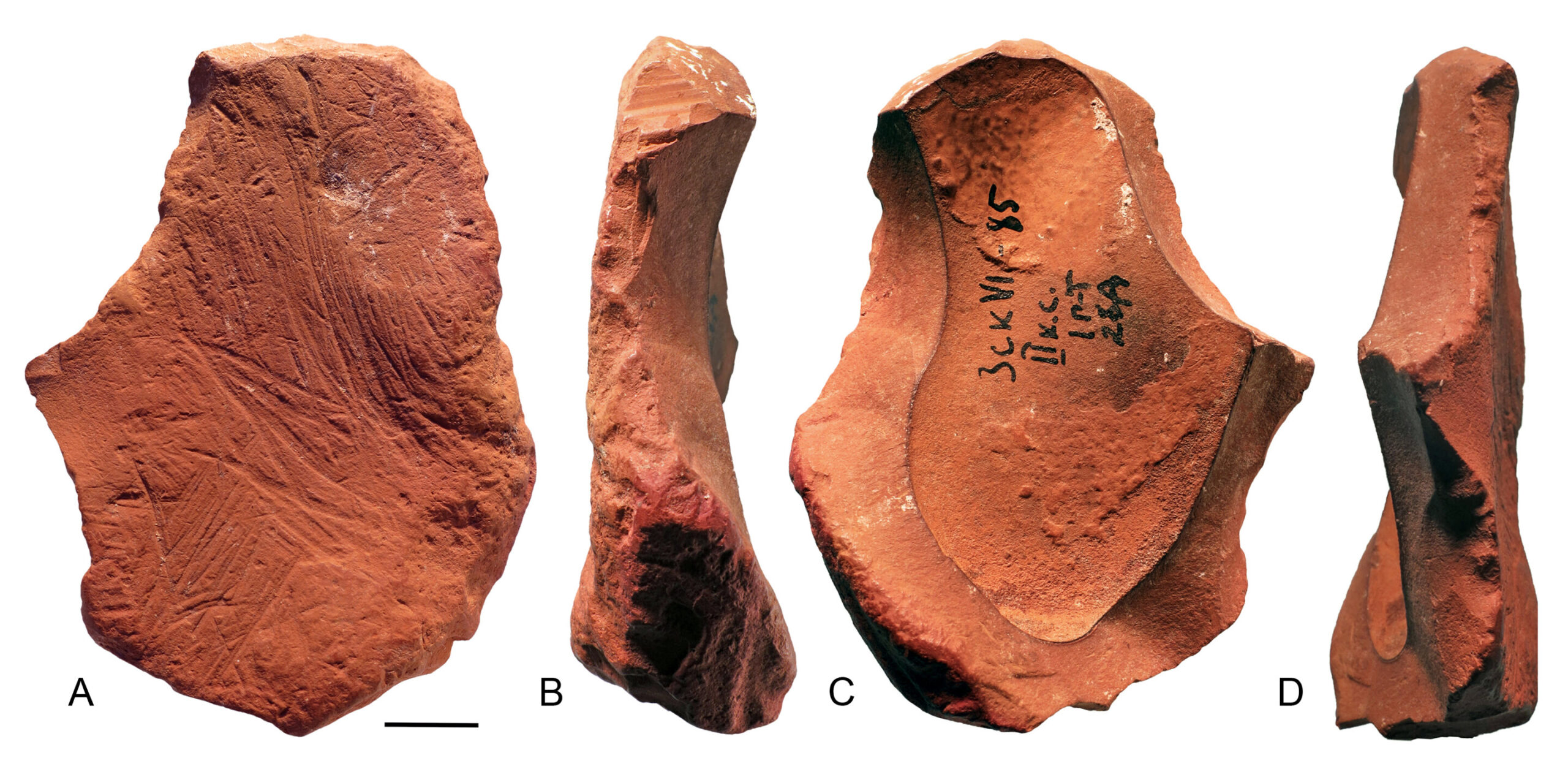

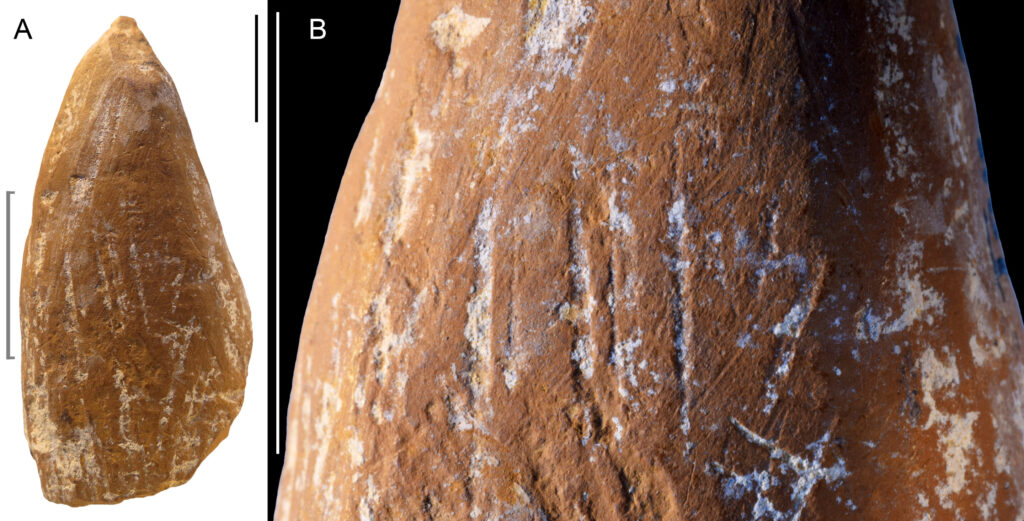

Among the most striking finds was a yellow ochre fragment from the Micoquian Age—a period stretching between 130,000 and 33,000 years ago. The piece wasn’t just worn by use; it was carefully shaped into a pointed tool. Its edges showed evidence of deliberate scraping and repeated sharpening. This was no random lump of mineral—it was a crayon.

The analysis showed that the tip had been used many times, suggesting it served as a mark-making instrument. Whether it drew on stone, hide, or skin, it was clearly used for more than just practical coloring. It was a tool for expression.

“The deliberate shaping and reuse of crayons, the engraved motifs, and the evidence for curated tools collectively support the conclusion that at least some ochre materials were involved in symbolic activities,” wrote the researchers in Science Advances.

This finding represents more than just the earliest example of artistic tools—it’s evidence of abstract thought. A crayon, after all, is not only an object but a bridge between the mind and the material world. To create and reuse one means to plan, imagine, and care about the outcome.

Traces of Creativity and Meaning

The ochre fragments tell an intimate story of the Neanderthal mind. Another piece showed engraved and polished surfaces with clear signs of intentional shaping. A third bore microscopic traces of grinding and sharpening, hinting at a similar purpose.

These details might seem small, but they carry immense weight. They suggest that Neanderthals weren’t merely using tools—they were creating tools for making symbols. And that’s something profoundly human.

Symbolic behavior is one of the hallmarks of modern intelligence. It represents the ability to create meaning beyond survival—to communicate, to decorate, to imagine. By marking a surface, Neanderthals may have been recording their world, expressing identity, or sharing ideas in ways that words cannot capture.

Redefining the Neanderthal Mind

For much of history, Neanderthals were cast as the dull cousins of Homo sapiens—living in caves, grunting, surviving, but never thinking deeply. This caricature was partly due to the tools and artifacts early archaeologists found: crude stone implements, animal bones, and little else. But over time, new discoveries have painted a far richer picture.

We now know that Neanderthals made jewelry from shells, used feathers for decoration, buried their dead, and possibly created cave art. They hunted cooperatively, cared for the injured, and likely used spoken language. The evidence from these ochre tools strengthens the case that they also possessed symbolic thought—the ability to assign meaning and beauty to the world around them.

This challenges the long-standing notion that artistic expression began only with modern humans. If Neanderthals were drawing or marking surfaces 70,000 years ago, then the roots of symbolic behavior run deeper in the human family tree than we ever imagined.

The Power of Color in a Cold World

It’s easy to forget that Neanderthals lived through ice ages—harsh, frozen environments where survival required every bit of resourcefulness. In such a world, color must have been rare and precious. The discovery that they deliberately collected, shaped, and reused ochre suggests it held special meaning.

Perhaps it was used in rituals or as body paint during group gatherings. Maybe it marked tools, clothing, or shelter walls. In the absence of written records, we can only speculate. But what is certain is that color had value. In shaping their crayons, Neanderthals were shaping their identities.

The use of ochre may have also been social—a way to bond groups, communicate status, or express belonging. In humans, color has always been tied to symbolism and emotion. A splash of red or yellow in a gray world could have meant hope, identity, or memory.

Science Illuminating the Ancient Mind

The precision of this research is as fascinating as its implications. Francesco d’Errico and his team applied cutting-edge technology to ancient fragments no bigger than a thumb. Under electron microscopes, they could see microscopic grooves and striations—tiny clues of scraping, grinding, and shaping. X-ray analysis revealed the mineral composition of each piece, helping to trace where the ochre was gathered and how it was processed.

This level of detail allows scientists to reconstruct behaviors from tens of thousands of years ago. It transforms fragments of mineral into windows into the Neanderthal soul. Each scrape and polish is a whisper from the past, a sign of thought, patience, and intention.

Beyond the Stereotype: The Neanderthals We Didn’t Know

Findings like these continue to reshape how we view Neanderthals. Far from being brutish cave dwellers, they were complex beings capable of culture, creativity, and care. Their brains were as large as ours, and now we see growing proof that their behaviors were just as sophisticated.

They weren’t merely surviving—they were expressing. They were thinking symbolically, perhaps even spiritually. This not only humanizes them but forces us to rethink what it means to be human in the first place.

The traditional boundary that separated “us” from “them” grows thinner with each discovery. The ochre crayons of Crimea and Ukraine are not just archaeological artifacts—they are reminders that creativity and expression are ancient, shared traits that connect all members of the human family.

The Dawn of Symbolic Thought

Symbolism—the ability to let one thing stand for another—is one of the defining features of human consciousness. It’s what allows us to use language, art, and ritual. If Neanderthals were marking surfaces intentionally, they were practicing a form of symbolic thought long before modern humans dominated Europe.

That means creativity and communication are not recent evolutionary flukes; they are ancient and deeply ingrained in our shared ancestry. These findings push back the timeline of when culture began. The first artists may not have been Homo sapiens at all—but Neanderthals, sketching the world in ochre long before history began.

Rediscovering Our Shared Humanity

In many ways, the story of Neanderthal ochre is a story about us. For decades, we’ve sought to define ourselves by our differences from them—our art, our language, our technology. But with every discovery, we find fewer differences and more continuity.

These ancient crayons blur the line between species. They remind us that imagination did not begin with us; it evolved long before, in beings who felt, thought, and created as we do.

Perhaps somewhere in a cave 70,000 years ago, a Neanderthal dipped their crayon into the ochre dust, pressed it against stone, and left a mark. That mark—whether a line, a symbol, or a handprint—was more than a stroke of color. It was an act of connection, a moment of thought made visible.

The Legacy of the First Artists

The fragments found in Crimea and Ukraine are small, but their significance is vast. They speak to a moment in evolution when humans—whatever their species—began to see the world not only as it was, but as it could be represented.

They remind us that creativity is not bound by time or species. It is an ancient inheritance, passed down from those who first saw beauty in the earth’s colors and meaning in a simple mark.

And so, the next time we think of Neanderthals, perhaps we should imagine not a crude figure hunched in darkness, but an artist—one who ground ochre into powder, shaped a crayon with care, and brought color to a cold world.

In that image, we find not a distant cousin, but a reflection of ourselves.

More information: Francesco d’Errico et al, Evidence for symbolic use of ochre by Micoquian Neanderthals in Crimea, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adx4722