Every time we sit down to eat, we may unknowingly be shaping the fate of life on Earth. A groundbreaking new study from the University of Cambridge has revealed just how closely our diets are linked to the survival—or extinction—of other species. The findings are sobering: unless the way the world uses land for agriculture changes, between 700 and 1,100 vertebrate species could disappear forever within the next century.

The Hidden Footprint of Our Food

The study, published in Nature Food, shines a light on an often-overlooked truth: the greatest driver of biodiversity loss today isn’t pollution or climate change—it’s the way we grow food. By converting forests, grasslands, and wetlands into farmland, humans have fundamentally reshaped nearly a third of the Earth’s land surface in just six decades.

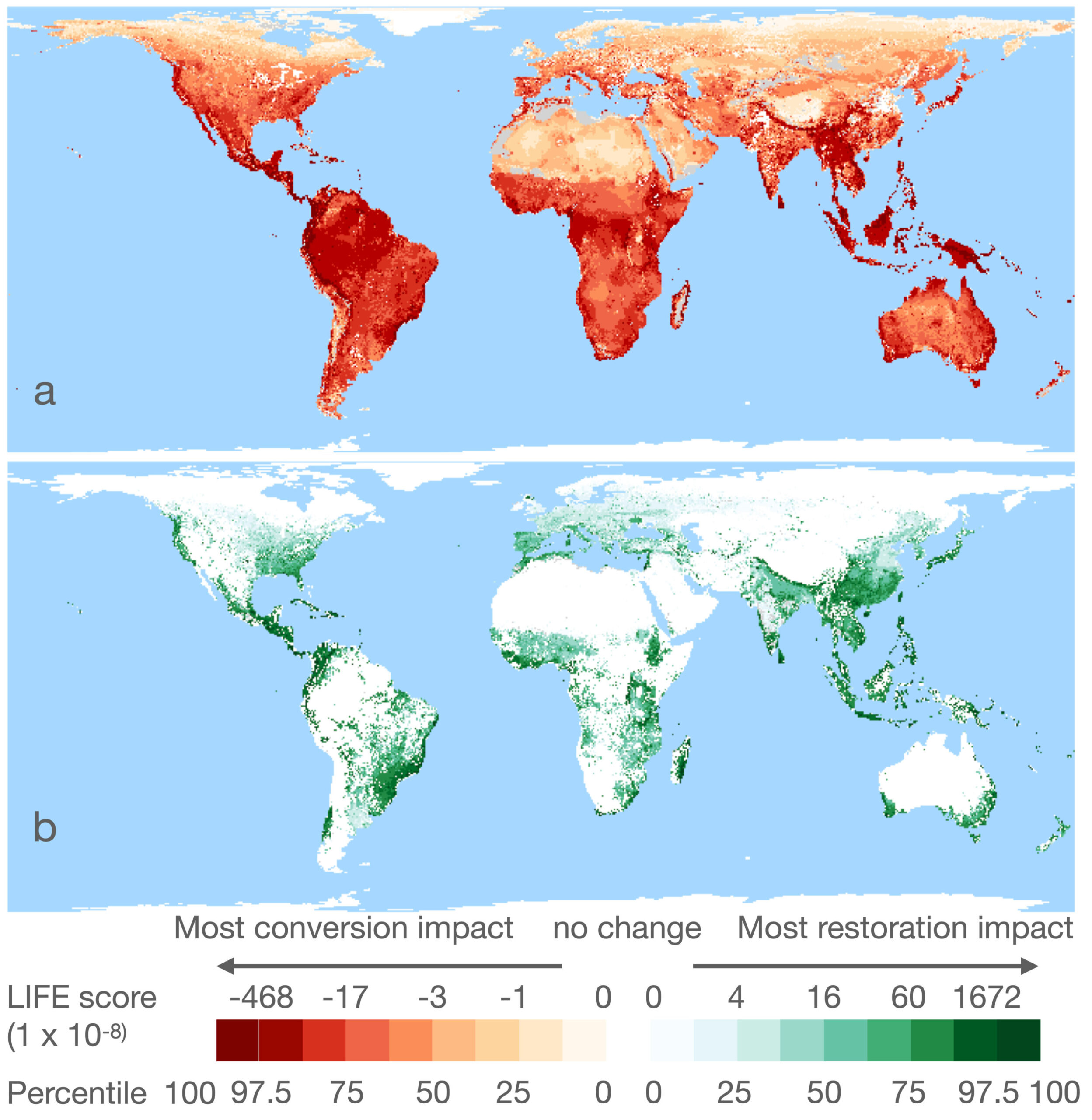

But the new research doesn’t just count hectares or tally species—it goes deeper. The Cambridge team developed a powerful new tool called the LIFE metric (short for Land-cover change Impacts on Future Extinctions). This system allows scientists to calculate the “per kilogram impact” of different foods on biodiversity—essentially, how much each product contributes to the risk of species extinction per year, based on the land needed to produce it.

Dr. Thomas Ball, lead author of the study from the University of Cambridge’s Department of Zoology, explained the significance: “Every time anyone eats anything, it has an impact on the other species we share the planet with.”

Tropical Treasures, Hidden Costs

Many of our favorite foods—coffee, cocoa, tea, and bananas—come from the tropics, regions brimming with life. The lush rainforests of South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia are home to an extraordinary range of species, from hummingbirds and jaguars to orchids and frogs. But that same richness makes these ecosystems especially fragile.

When tropical forests are cleared for plantations or pastures, the damage to biodiversity is far greater than when temperate ecosystems are altered. A single field of coffee or cocoa may replace what was once a vibrant forest filled with hundreds of interconnected species.

The Cambridge researchers found that commodities grown in these regions have a much greater impact on species extinction than similar foods produced in less biodiverse areas. What this means is that a morning cup of coffee or a bar of chocolate, while small indulgences to us, may carry a much heavier ecological cost than we imagine.

The Costliest Food of All

Among all the foods studied, beef and lamb stood out as the most destructive for biodiversity. The reason is simple but profound: raising cattle requires vast amounts of land. Forests, savannas, and grasslands are cleared to make room for grazing or to grow animal feed crops. Each hectare converted this way means less habitat for wild species.

Dr. Ball notes that “rearing the cattle for one kilo of beef needs a huge amount of land, which displaces a lot of natural habitat. On average, that has a much bigger impact on species’ survival than growing one kilo of vegetable protein like beans or lentils.”

The numbers are staggering. The study estimates that eating beans or lentils is 150 times better for biodiversity than eating the same weight of beef from ruminant animals. Even a partial shift in diet could make a meaningful difference. “If everyone in the UK switched to a vegetarian diet overnight,” said Ball, “we could halve our biodiversity impact.”

Britain’s Extinction Footprint

Perhaps the most striking revelation from the research concerns the global reach of the UK’s food system. Though the UK has relatively strict environmental standards, its appetite for imported food means that much of its biodiversity footprint lies overseas.

According to the study, the UK’s “extinction footprint” is almost entirely due to imports. Since Brexit, for instance, Britain has increased its imports of beef from Australia and New Zealand. Yet beef from those countries is 30 to 40 times more likely to contribute to species extinctions than beef produced in the UK or Ireland.

This means that while UK farmers may be reducing land use at home and even setting aside more land for wildlife, the environmental savings are effectively being “outsourced.” As Dr. Ball warns, “It’s not enough to focus on one country in isolation. If reducing food production in the UK means relying more on imports from more biodiverse places, it could cause far more damage to species on our planet in the long run.”

A Tool to Guide Global Policy

The LIFE metric isn’t just an academic model—it’s already shaping real-world decisions. Developed in collaboration with Dr. Jonathan Green of the Stockholm Environment Institute and the UK’s Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC), the metric is now part of the UK government’s toolkit for assessing the global environmental impacts of food consumption.

By combining national data on 140 different food types with information about where they’re produced, the LIFE metric can predict how changes in trade policy, agricultural subsidies, or consumer habits might affect species extinction risks around the world. It’s the first time such a comprehensive approach has ever been attempted.

This new system allows policymakers to see the bigger picture: how the food choices of one nation ripple outward across ecosystems thousands of miles away. For example, encouraging domestic rewilding or reducing livestock herds might look beneficial within national borders—but could backfire if it leads to greater imports from ecologically sensitive regions.

The Global Food Crisis for Nature

The study comes at a critical time. The world’s population is expected to exceed 9 billion by 2050, and global food demand is projected to rise by more than 50 percent. Unless agriculture becomes more efficient and sustainable, this expansion will come at an enormous cost to nature.

Already, agriculture is responsible for 80 percent of global deforestation and the majority of habitat loss on land. From orangutans in Borneo to jaguars in the Amazon, countless species are losing their homes to make room for crops and livestock.

Yet the researchers stress that it doesn’t have to be this way. The LIFE metric can help identify where changes in land use will cause the least harm—and where restoration efforts could do the most good. By using this tool, nations and companies can make smarter choices about what they produce, import, and consume.

The Power of What We Eat

The findings also carry a personal message. Each of us contributes, in small but cumulative ways, to the global footprint of food. While the choices of individuals alone can’t solve the biodiversity crisis, they can help shift demand toward more sustainable patterns.

Opting for plant-based meals, reducing red meat consumption, and supporting sustainably certified products can collectively ease pressure on ecosystems. Equally important is demanding that governments and industries take responsibility for the global consequences of their food systems.

As Dr. Ball and his team emphasize, protecting biodiversity isn’t about giving up modern comforts—it’s about recognizing the hidden relationships that sustain life. Every bite of food connects us to the natural world, from the soil microbes that nourish crops to the rainforests that regulate our climate.

A New Way Forward

What makes this Cambridge study remarkable is not just its warning, but its hope. For the first time, humanity has a clear, quantifiable way to measure how our food systems affect the planet’s living fabric. The LIFE metric offers a path to more informed decisions—ones that balance human needs with the survival of other species.

If governments, industries, and consumers work together to rethink land use and trade policies, it may still be possible to prevent hundreds of extinctions in the coming century. But the window is narrow. Each field plowed, each forest felled, each meal consumed carries a choice.

The fate of thousands of species may depend on how we choose to grow, trade, and eat our food. As the Cambridge researchers remind us, biodiversity loss is not an inevitable consequence of human progress—it’s a reflection of our priorities. Changing those priorities could be one of the most powerful steps humanity ever takes to protect the living world.

More information: Thomas S. Ball et al, Food impacts on species extinction risks can vary by three orders of magnitude, Nature Food (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s43016-025-01224-w