In the vast, resource-rich landscapes of Canada, a hidden climate threat is silently leaking into the atmosphere. A new study led by researchers at McGill University has uncovered a staggering discrepancy in the nation’s methane emissions: non-producing oil and gas wells—those that are no longer actively extracting fossil fuels—may be emitting methane at levels seven times higher than the official government estimates suggest. This revelation throws a wrench into Canada’s greenhouse gas reporting and underlines a serious blind spot in how the country is tracking its progress toward climate goals.

Uncovering the Methane Mystery

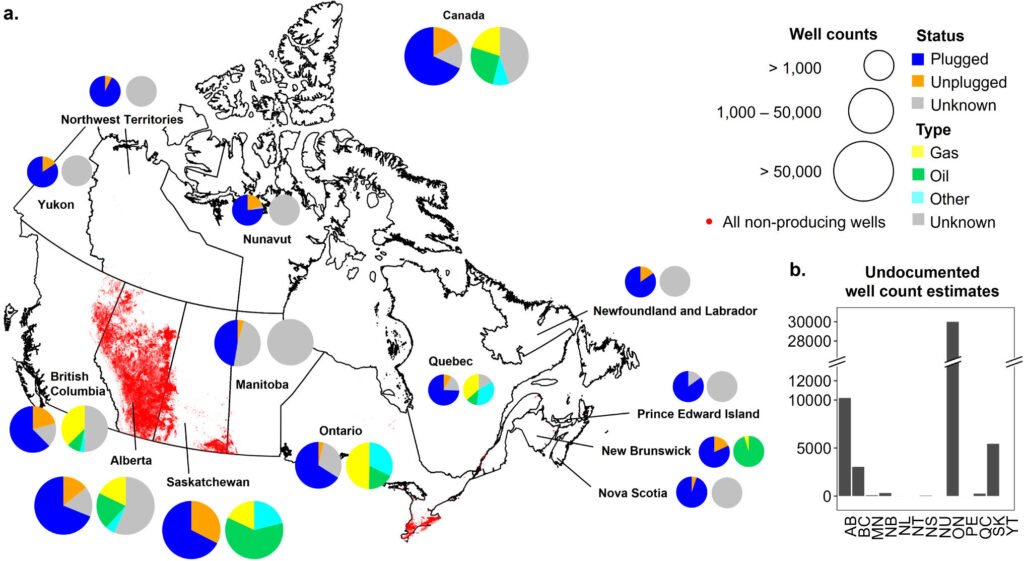

The groundbreaking study, recently published in Environmental Science & Technology, is the most comprehensive investigation yet into the methane emissions of Canada’s dormant oil and gas wells. Led by Associate Professor Mary Kang from McGill’s Department of Civil Engineering, the research team conducted on-site measurements of 494 non-producing wells across five provinces. These wells, scattered across Alberta, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Ontario, and New Brunswick, represent a mere 0.1 percent of Canada’s total inactive well count—yet the implications of their emissions are enormous.

Using a chamber-based measurement technique—essentially a sophisticated method of “capturing” the gases released at the wellhead—the researchers collected direct methane readings while analyzing key characteristics such as the well’s age, depth, gas or oil type, and whether it had been sealed with cement (known as “plugging”).

The result? An estimate that Canada’s non-producing oil and gas wells collectively emit 230 kilotonnes of methane annually—a figure that dwarfs the official 34 kilotonnes listed in Canada’s National Inventory Report. This represents a vast underestimation and exposes a major credibility gap in how Canada is accounting for one of its most potent greenhouse gases.

Why Methane Matters So Much

Methane doesn’t linger as long in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, but during its short life—about two decades—it punches far above its weight in terms of global warming potential. Over a 20-year timeframe, methane traps approximately 80 times more heat than the same amount of CO₂. It’s also linked to air quality deterioration and health risks, particularly for communities living near oil and gas infrastructure.

This means that tackling methane emissions is a fast and effective way to slow global warming in the short term. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has identified methane reduction as a key lever in keeping planetary warming below the dangerous 1.5°C threshold. But doing so requires accurate data. And right now, according to Kang and her team, Canada is flying blind.

“If we don’t have accurate estimates of methane emissions, we can’t design effective climate policies,” said Kang. “It’s like trying to fix a leak in your house without knowing where the water is coming from.”

The Invisible Giants: Unplugged and Forgotten Wells

The study’s findings don’t just reveal that more methane is escaping than previously believed—they also shed light on which wells are the worst offenders. It turns out that a small fraction of unplugged gas wells are doing most of the damage. In fact, the highest emission rate ever recorded from a non-producing well in Canada was detected during this study.

“These ‘super-emitters’—old, unplugged gas wells—are low-hanging fruit for emissions mitigation,” Kang explained. “We don’t need to monitor every single well. If we target the wells that are likely to be the highest emitters, we can achieve significant reductions efficiently.”

This insight is critical, especially when you consider that Canada has more than 425,000 inactive oil and gas wells—with the majority located in Alberta and Saskatchewan. Monitoring each one would be logistically impossible and prohibitively expensive. But if we can identify patterns—based on factors like the well’s age, depth, or whether it was ever properly sealed—regulators can prioritize their monitoring and cleanup efforts.

A Patchwork of Policies, A Web of Emissions

One of the study’s more surprising findings was the variability in emissions drivers across provinces. While it might be expected that geological differences—such as rock formations or gas pressure—would explain the disparities, Kang’s team found that policy and operational differences between provinces were actually more influential.

“Things like inspection routines, enforcement, plugging standards, and record-keeping vary from one province to another,” said Kang. “And those differences can have a major impact on how much methane is leaking.”

This suggests that improving national methane control efforts isn’t just a scientific or technical problem—it’s a political and regulatory one. Bringing uniformity and stringency to policies governing well abandonment and emissions monitoring could go a long way in reducing Canada’s methane footprint.

The Hidden Cost of Inaction

The financial and environmental cost of these emissions is substantial. Methane not only accelerates climate change but represents a lost resource—a fuel that could be captured and sold if the infrastructure existed to do so. Instead, it seeps unnoticed from neglected wells, polluting the air and undermining Canada’s climate credibility.

There’s also a social cost. Many of these wells are located near rural or Indigenous communities who are already bearing the brunt of environmental degradation. Unplugged wells can leak not just methane, but also other volatile organic compounds, posing health and safety risks to nearby residents.

Moreover, abandoned wells often become “orphaned”—left behind by companies that have gone bankrupt or shirked their cleanup responsibilities. This leaves the burden of remediation on provincial governments and, ultimately, taxpayers.

Turning a Liability into an Asset

Despite the bleak findings, the study also opens the door to new opportunities. Rather than simply sealing and forgetting these wells, researchers and environmental groups are exploring ways to repurpose abandoned sites into assets for the clean energy transition.

“There’s potential to repurpose these sites in ways that generate funding for long-term monitoring and emissions reduction,” Kang noted.

One promising idea is to convert old well sites into locations for solar, wind, or geothermal energy production. Because these sites are already cleared and connected to energy infrastructure, they can serve as ideal locations for new energy projects—especially in provinces like Alberta where renewable energy is gaining momentum.

Ph.D. student and co-author Jade Boutot highlighted this vision: “Many of these sites can be transformed to produce clean energy. We can turn a legacy of fossil fuel extraction into a new chapter of renewable energy development.”

Charting a Way Forward

The path to a methane-smart future begins with better data. Direct measurements, like those used in this study, offer a far more accurate picture of emissions than models or estimates alone. But scaling up this type of research will require investment, political will, and cross-sector collaboration.

Regulatory agencies must enhance requirements for well monitoring and enforce standards for plugging and reclamation. Provinces need to close policy gaps and align their practices. The federal government, in turn, must revise its methane estimates and reporting methodologies to reflect reality, not outdated assumptions.

Canada has already pledged to cut methane emissions from the oil and gas sector by at least 75 percent by 2030 under the Global Methane Pledge. But pledges are only as strong as the data they’re built on. If the government is underestimating emissions by a factor of seven, then current reduction strategies are grossly inadequate.

A Call to Action

This study by McGill University is more than just a scientific investigation—it’s a call to action. It urges Canada to reexamine its assumptions, rethink its policies, and reimagine its energy legacy. Methane may be invisible, but its impacts are not. And while non-producing wells might be forgotten by industry, they must not be ignored by policymakers or the public.

As the world races to slow climate change, methane stands out as a high-impact area where change is both possible and powerful. Canada’s vast reserves of abandoned wells are both a symbol of a fossil-fuelled past and a crucial battleground for a climate-conscious future. Whether we view them as a threat or an opportunity depends on the choices we make today.

Reference: Louise A. Klotz et al, Sevenfold Underestimation of Methane Emissions from Non-producing Oil and Gas Wells in Canada, Environmental Science & Technology (2025). DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.4c05602