In the 1980s, the world witnessed only a couple of catastrophic wildfires each year—devastating events, yes, but still rare enough to be considered exceptional. Today, those fires have become frighteningly ordinary. According to new research published in Science, Earth’s most destructive wildfires are now blazing more than four times as often as they did four decades ago. This surge, scientists warn, is no coincidence. It is being fueled by the twin forces of human-caused climate change and the steady migration of people into fire-prone landscapes.

The study does not focus on acres burned, the usual metric of fire size, but on what truly matters: human and economic toll. When measured in ruined lives, homes, and national economies, the numbers tell a story that is impossible to ignore—a story of a world in flames, burning hotter and more often because of decisions made by humanity.

A Crisis Written in Fire

The team of researchers from Australia, Germany, and the United States compiled data on the 200 most destructive fires worldwide since 1980. They measured devastation not just in flames, but in lost GDP, adjusted for inflation and scaled to national economies. Their conclusion: the frequency of these catastrophic events has increased by a factor of 4.4 in less than half a century.

Lead author Calum Cunningham, a pyrogeographer at the Fire Centre of the University of Tasmania, put it starkly: “It shows beyond a shadow of a doubt that we do have a major wildfire crisis on our hands.”

The numbers are sobering. About 43 percent of the world’s most disastrous wildfires recorded since 1980 occurred in just the last ten years. During the 1980s, catastrophic fires averaged around two per year. By the past decade, that number had jumped to nearly nine annually, peaking at thirteen in 2021. Something changed dramatically around 2015, when the number of destructive blazes began climbing in tandem with more extreme weather linked to global warming.

Geography of Destruction

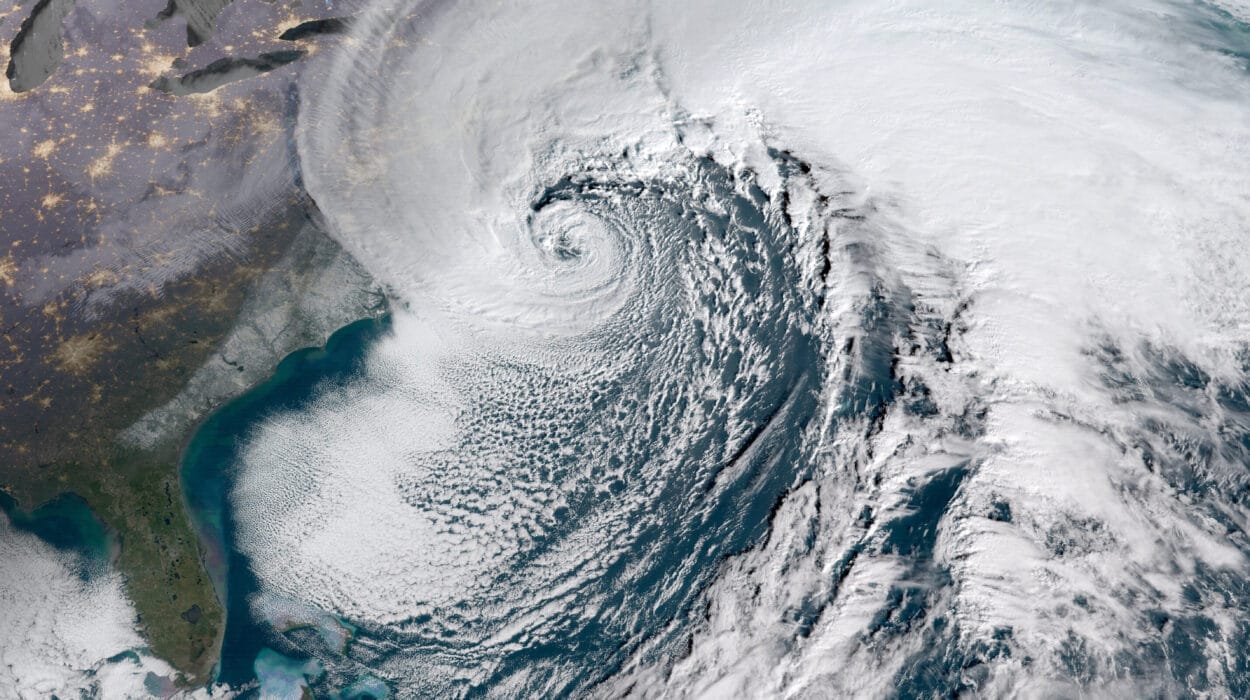

Although wildfires are a global phenomenon, the burden falls disproportionately on certain regions. Europe and North America, particularly the Mediterranean countries of Greece, Italy, Spain, and Portugal and the fire-prone western United States, account for many of the most destructive events. These are landscapes where seasonal dryness collides with hotter temperatures, more intense winds, and the steady encroachment of human settlements.

The devastation is not only measured in dollars but also in lives. Researchers found that the number of fires killing at least ten people has tripled since 1980. Infamous examples include the 2018 Camp Fire that destroyed Paradise, California, the 2023 inferno that swept through Lahaina, Hawaii, and repeated tragedies in Los Angeles. These were not necessarily the largest fires by area, but they struck where people lived, turning homes into ash and futures into grief.

As Cunningham noted, measuring destruction by acres alone misses the true story. A fire that tears through a remote forest may burn vast tracts of land, but if no one lives there, its social impact is small compared to a smaller blaze that annihilates a town. The Lahaina fire, for instance, covered relatively little ground yet became one of the deadliest and most destructive wildfires in American history.

The Human Fingerprint

Why are these fires happening more often, and why are they becoming deadlier? The research points to multiple causes, but one stands above the rest: climate change. Burning fossil fuels—coal, oil, and gas—has pushed global temperatures upward, and with heat comes drought, dryness, and extreme weather.

Cunningham explained that nearly every catastrophic fire examined in the study occurred under conditions of “fire weather”: hot, dry, and windy days when landscapes turn into tinderboxes. The data show these conditions are becoming more common, and the culprit is unmistakable—climate change driven by human activity. “That’s indisputable,” Cunningham said. “We are loading the dice by increasing temperatures.”

Yet climate is not the only factor. More people are moving into what scientists call the wildland-urban interface—the borderlands where forests meet communities. These are beautiful places to live, but they are also perilously vulnerable to fire. Once a blaze begins, the combination of natural fuels like dry foliage and human structures creates a deadly synergy. Houses become accelerants, flames leap from rooftop to rooftop, and communities are consumed before firefighters can mount a defense.

Adding to the danger is humanity’s failure to manage fire-prone ecosystems. Decades of suppressing smaller fires have left many landscapes overloaded with fuel—dead trees, dry brush, and dense undergrowth—that ignite with catastrophic intensity when sparks inevitably come.

The Hidden Costs

One of the most innovative aspects of this study lies in how the researchers measured fire damage. Economic data is notoriously difficult to obtain, with many governments keeping information private. To overcome this, the team drew on more than four decades of global economic records from the insurance giant Munich Re, as well as disaster databases maintained by academic institutions. This allowed them to calculate damages in terms of economic impact relative to a country’s GDP, offering a clear view of how deeply each fire scarred a nation’s economy.

This shift in measurement is crucial. By looking at wildfires through the lens of human impact rather than acres alone, the study underscores the real stakes: homes destroyed, lives lost, economies strained, and ecosystems pushed past recovery.

Voices of Alarm

Independent experts not involved in the research have echoed its warnings. Jacob Bendix, a geography professor at Syracuse University, called the study “innovative” and said it confirmed what many had long suspected: the most disastrous fires happen in populated areas during increasingly extreme fire weather conditions.

Mike Flannigan, a wildfire researcher at Thompson Rivers University, emphasized the grim trajectory. “As the frequency and intensity of extreme fire weather and drought increases,” he said, “the likelihood of disastrous fires increases so we need to do more to be better prepared.”

These are not just academic cautions. They are urgent reminders that societies around the world are already living in a new era of fire.

A Future on Fire?

If current trends continue, the future could be more dangerous than most people imagine. Even with aggressive climate action, the Earth is expected to get warmer in the coming decades. That means more extreme heatwaves, longer droughts, and higher risks of explosive fire weather.

Without systemic changes—reducing greenhouse gas emissions, rethinking where and how we build communities, managing forests with both ecological and human safety in mind—the number of catastrophic wildfires will only grow. This is not a distant scenario but a present reality unfolding each summer and autumn, each fire season longer than the last.

What Can Be Done

The challenge is immense, but there are paths forward. Scientists argue that reducing fossil fuel use is non-negotiable if we hope to slow the worsening fire weather. Urban planners and governments must also rethink development in fire-prone areas, balancing the desire for scenic living with the responsibility of safety. Proactive forest management, such as controlled burns and removal of excess deadwood, can reduce the intensity of future fires.

Perhaps most importantly, societies must invest in resilience—stronger firefighting systems, better warning networks, community education, and international cooperation. Fires do not respect borders, and neither should the solutions.

The Human Story Behind the Flames

Numbers alone cannot capture what it means to lose everything in a wildfire. Behind every statistic are families displaced, memories reduced to ash, and landscapes forever altered. The Lahaina fire left residents mourning not just homes but an entire cultural heritage site. California’s Paradise fire obliterated a town, scattering its community across the country. Across the Mediterranean, centuries-old olive groves and vineyards burned, erasing livelihoods rooted in tradition.

Wildfires are not only ecological events; they are human tragedies. They reveal how vulnerable we are, but they also show how interconnected we are with the climate, the land, and each other.

Conclusion: Living With Fire

The evidence is undeniable: wildfires are escalating in frequency, ferocity, and cost. They are not solely acts of nature but also consequences of human choices—our consumption of fossil fuels, our movement into fire-prone areas, our mismanagement of ecosystems. We cannot prevent all fires, nor should we—fire is a natural force. But we can and must prevent the worst disasters.

As the world grows hotter, the line between a manageable blaze and a catastrophic inferno grows thinner. The flames we face now are not just burning forests; they are burning warnings into our future. The question is whether we will heed them.

Humanity’s relationship with fire has always been double-edged. Fire gave us warmth, protection, and civilization. Now, if we do not act, it may become the force that undoes much of what we have built.

The planet is telling us something in the language of smoke and flame: we are living in a new era of fire. The choice before us is simple but stark—adapt, mitigate, and prepare, or face a world where wildfire becomes the defining disaster of our time.

More information: Calum X. Cunningham et al, Climate-linked escalation of societally disastrous wildfires, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adr5127