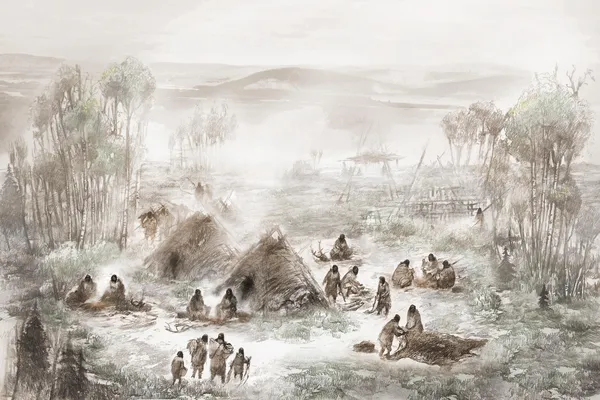

When we imagine the diets of early humans, it is easy to picture small game roasting over an open fire, berries gathered from nearby bushes, or perhaps fish caught in primitive nets. But a new study from archaeologists in Argentina suggests that the story is far more dramatic—and far more monumental. Around 13,000 to 11,600 years ago, the dinner tables of early humans in South America were filled not with rabbits or deer but with giants.

These ancient hunter-gatherers were eating extinct megafauna—massive animals like giant sloths and armadillo-like creatures as large as cars. The discovery, published in Science Advances, paints a picture of a world where humans dined on the last giants of the Ice Age. It also raises profound questions about whether our ancestors were simply surviving or whether their appetites may have helped drive these magnificent creatures into extinction.

The Giants of the Ice Age

To understand the significance of the discovery, one must first imagine the world as it was at the close of the last Ice Age. Vast grasslands stretched across southern South America, and roaming these plains were animals unlike anything we see today. Giant ground sloths, some standing over four meters tall, moved slowly but powerfully through the landscape. Glyptodons, giant relatives of armadillos with massive armored shells, lumbered in herds. Herds of huge, prehistoric horses and camel-like guanacos shared the terrain.

These animals were not just rare curiosities. They were abundant, providing an immense storehouse of meat, fat, and marrow. For early humans—small bands of hunter-gatherers armed with stone tools and courage—the opportunity was irresistible. Hunting a giant sloth was not just about survival; it was about energy, sustenance, and survival strategy.

Reading the Bones of the Past

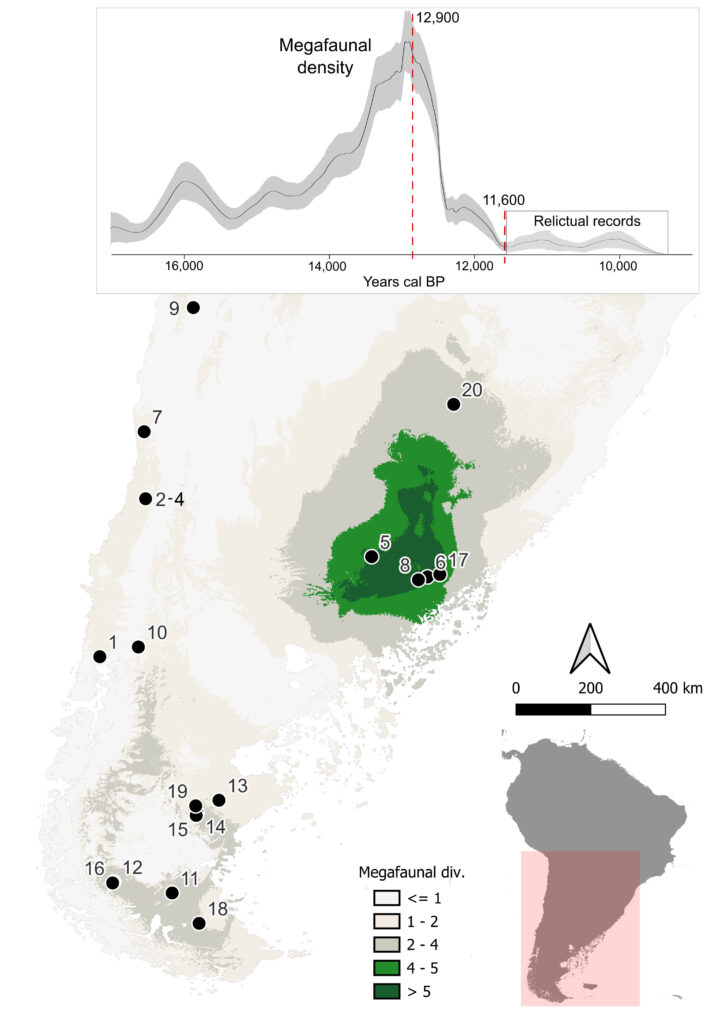

The archaeologists behind this study did not rely on imagination alone. Their work involved painstaking analysis of bones excavated from 20 archaeological sites across Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay. These sites were reliably dated to before 11,600 years ago, the point at which most of the South American megafauna disappeared.

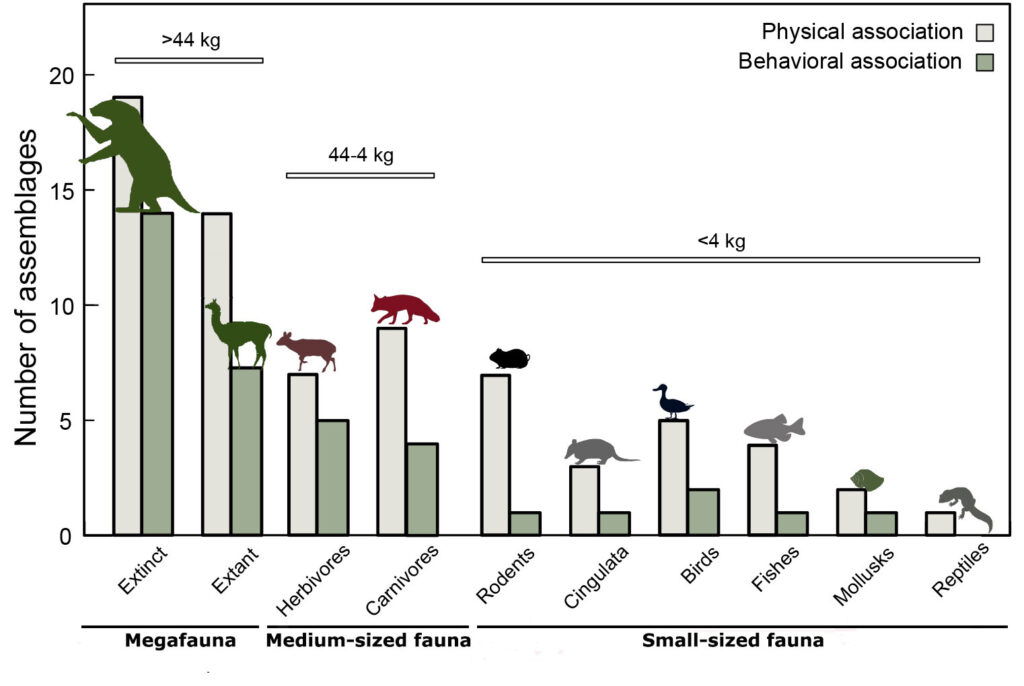

What they found was striking. At 15 of these sites, bones of extinct megafauna made up more than 80 percent of the remains. Not only were these bones present in overwhelming numbers, but they also bore the unmistakable marks of human butchering—cuts, scrapes, and fractures that tell the story of meat being stripped, bones being cracked for marrow, and carcasses carefully processed for maximum nourishment.

This was not opportunistic scavenging of a fallen animal. It was deliberate hunting. Early humans were targeting these giants systematically, and for good reason.

The Energy Equation

Hunting is never without risk. A giant sloth could swipe with powerful claws, and an armored glyptodon was no easy prey. Yet early humans seemed willing to take those risks, and a closer look at the nutritional returns explains why.

The team used a prey ranking model, calculating the energy payoff of different animals. The giants, unsurprisingly, topped the charts. A single kill could feed dozens of people for days or weeks. The fat content, so vital for survival in colder climates, was plentiful. By contrast, smaller animals like guanacos or deer offered far less energy for much more frequent effort.

The conclusion is clear: early humans were not simply opportunists, eating whatever came their way. They were strategic hunters, deliberately seeking out the biggest, most rewarding prey. In the language of survival, they were efficient, calculating, and successful.

Rethinking Extinction

For decades, scientists debated the cause of the disappearance of the Ice Age megafauna. The dominant explanation has been climate change. As the Ice Age ended, warming temperatures and shifting ecosystems were thought to have reduced habitats and food sources, gradually pushing these giants to extinction. Human hunting, in this view, played only a minor role.

But the new evidence challenges that narrative. If megafauna bones dominate archaeological sites, and if humans specifically hunted these animals for survival, then the role of humans in their extinction can no longer be considered incidental.

The researchers put it bluntly: their findings undermine one of the most widely cited objections to the idea that humans were a driving force behind the extinctions. Instead, humans stand once again at the center of the debate. The picture that emerges is not of climate slowly squeezing the giants out of existence but of human hunters playing a decisive role in their demise.

The Shift After the Giants

What happened when the giants disappeared? The archaeological record offers a poignant answer. After the extinction of the megafauna, early humans broadened their diet. Suddenly, guanacos, deer, smaller mammals, and even more plant resources became central to survival.

This shift suggests something important: humans only diversified their diets when the giants were no longer there. If climate change alone had removed the megafauna, humans might already have been eating smaller prey in significant amounts. But the fact that smaller prey became dominant only after the giants were gone strongly hints that human hunting pressure was the critical factor.

In other words, people hunted the giants into oblivion and then adapted to a new ecological reality.

Lessons from an Ancient Feast

The story of early humans eating giant sloths and armored beasts is not just about the past. It is a mirror for the present. Our species has always been capable of reshaping ecosystems through appetite and ingenuity. Thirteen thousand years ago, our ancestors brought down animals weighing several tons with stone-tipped spears. Today, we wield industrial-scale technologies that can transform entire biomes.

The extinction of the megafauna is a warning: survival strategies that make sense in the short term can have irreversible consequences in the long term. By seeking the biggest meal, the richest energy return, early humans may have eaten their way out of abundance and into scarcity.

And yet, this story is also one of resilience. Faced with the disappearance of their most prized food sources, humans adapted. They broadened their diets, innovated their tools, and found new ways to thrive. This capacity for flexibility—both destructive and creative—remains central to what it means to be human.

A Deeper Understanding of Ourselves

The tale of megafauna and the humans who hunted them is not only about bones and butchering marks. It is about who we are as a species. We are creatures of curiosity, courage, and calculation. We are capable of bringing down giants and of surviving their loss.

But we are also creatures of consequence. Every action reverberates across ecosystems and across time. The choices our ancestors made, born of hunger and survival, helped shape the world we inherited. Today, our choices will shape the world that future generations inherit.

So when we ask, “What did early humans like to eat?” the answer is not only giant sloths and glyptodons. The deeper answer is that they ate what gave them life, what gave them strength, and what allowed them to endure. And in doing so, they wrote a chapter in the long, complicated story of humanity’s relationship with the natural world—a story still unfolding around us.

More information: Luciano Prates et al, Extinct megafauna dominated human subsistence in southern South America before 11,600 years ago, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adx2615