For more than a century, scholars have looked to the fertile plains of southern Mesopotamia as the birthplace of urban life. Here, along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, the Sumerians built the first great city-states—Ur, Uruk, Lagash—and pioneered advances that shaped the course of human history. Writing, monumental temples, wheels turning on carts, and intensive agriculture all first flourished in this land. But why here, and why then?

A groundbreaking new study published in PLOS One is challenging long-standing assumptions. It suggests that the Sumerian miracle was not simply the product of rivers and fertile soil but the outcome of a far more dynamic and complex relationship: the ceaseless interplay of rivers, tides, and shifting sediments at the head of the Persian Gulf.

The research, led by Liviu Giosan of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Reed Goodman of Clemson University, reimagines the environmental foundations of Sumer. Their findings show that water was not only a tool but the very architect of early civilization.

The Landscape Beneath the Legends

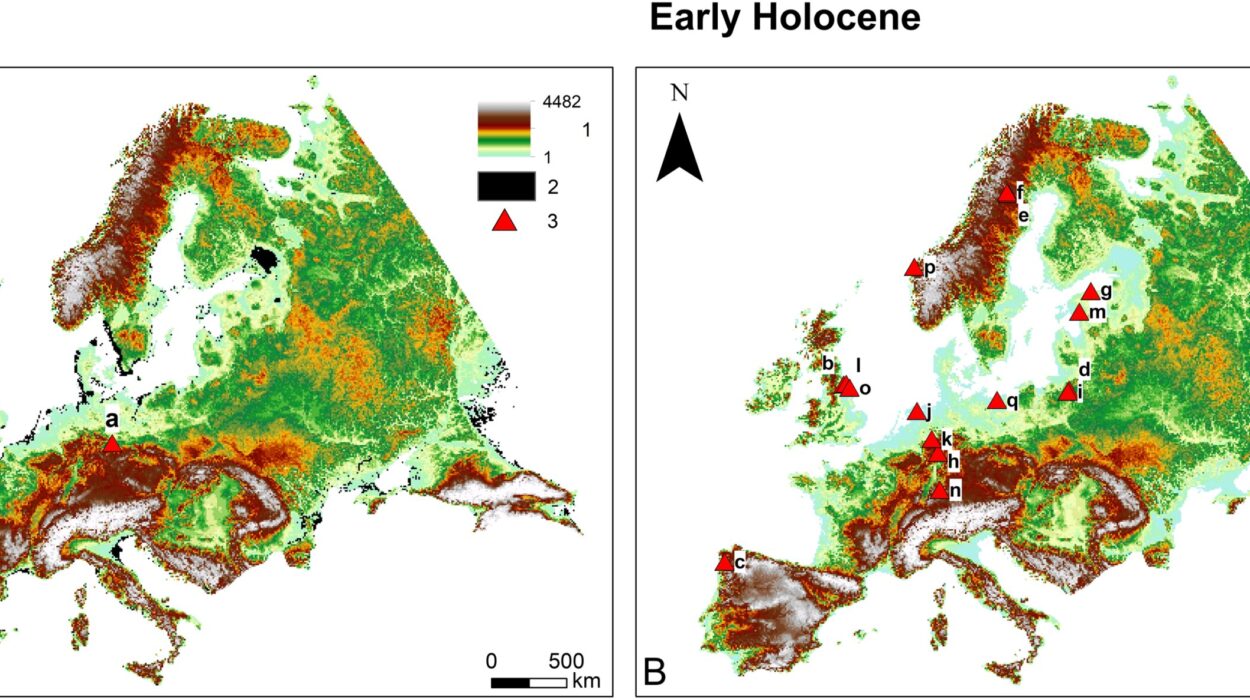

We often imagine the ancient Mesopotamian landscape as timeless: great rivers winding through flat plains, nourishing crops and sustaining cities. But the new study reveals a land in motion. Between 7,000 and 5,000 years ago, the Persian Gulf extended much farther inland than it does today, its tides pushing fresh water twice daily into the lower reaches of the Tigris and Euphrates.

For early communities living along these shifting margins, tides were a gift. They created a reliable, natural irrigation system. With only modest canals and ditches, villagers could direct tidal waters to nourish date groves and fields of grain. Unlike later periods, when massive irrigation works were necessary, this early tidal ecology offered abundance without bureaucracy.

Yet landscapes do not stand still. Over centuries, as the rivers deposited silt and expanded their deltas, the Gulf receded and tides could no longer reach far inland. This ecological shift severed the dependable rhythms of water that had sustained early communities. The loss of tides, the study suggests, triggered both crisis and opportunity.

Crisis and Reinvention

When the tides withdrew, so too did the natural irrigation system. Communities suddenly faced the challenge of sustaining agriculture in a less forgiving environment. What followed was a collective response of unprecedented ambition. To survive, they built the canals, levees, and irrigation networks that became hallmarks of Sumerian engineering.

This was not merely a technological leap—it was a social revolution. Large-scale water management required cooperation, labor organization, and political authority. Out of necessity emerged the first experiments in urban governance, inequality, and centralized power. Villages clustered into city-states, each ruled by leaders who claimed divine sanction to organize labor and control water.

As Giosan notes, “Sumer was literally and culturally built on the rhythms of water.” What had once been the gift of tides now became the mandate of kings. The environment’s challenge was the spark for civilization’s reinvention.

Myths Written in Water

The Sumerians themselves never forgot the restless waters that shaped their world. Their pantheon overflowed with deities of rivers, seas, and floods. Their myths—stories of gods taming chaos, of floods sent to cleanse humanity, of watery underworlds—echo the lived experience of communities struggling with shifting landscapes.

The famous Mesopotamian flood myth, later echoed in the Epic of Gilgamesh and the biblical story of Noah, may preserve a cultural memory of tidal surges and rising waters. In their stories, as in their society, water was never just background—it was destiny.

Reed Goodman, one of the study’s lead authors, reminds us: “We often picture ancient landscapes as static. But the Mesopotamian delta was anything but. Its restless, shifting land demanded ingenuity and cooperation, sparking some of history’s first intensive farming and bold social experiments.”

Lagash: A Window into the Past

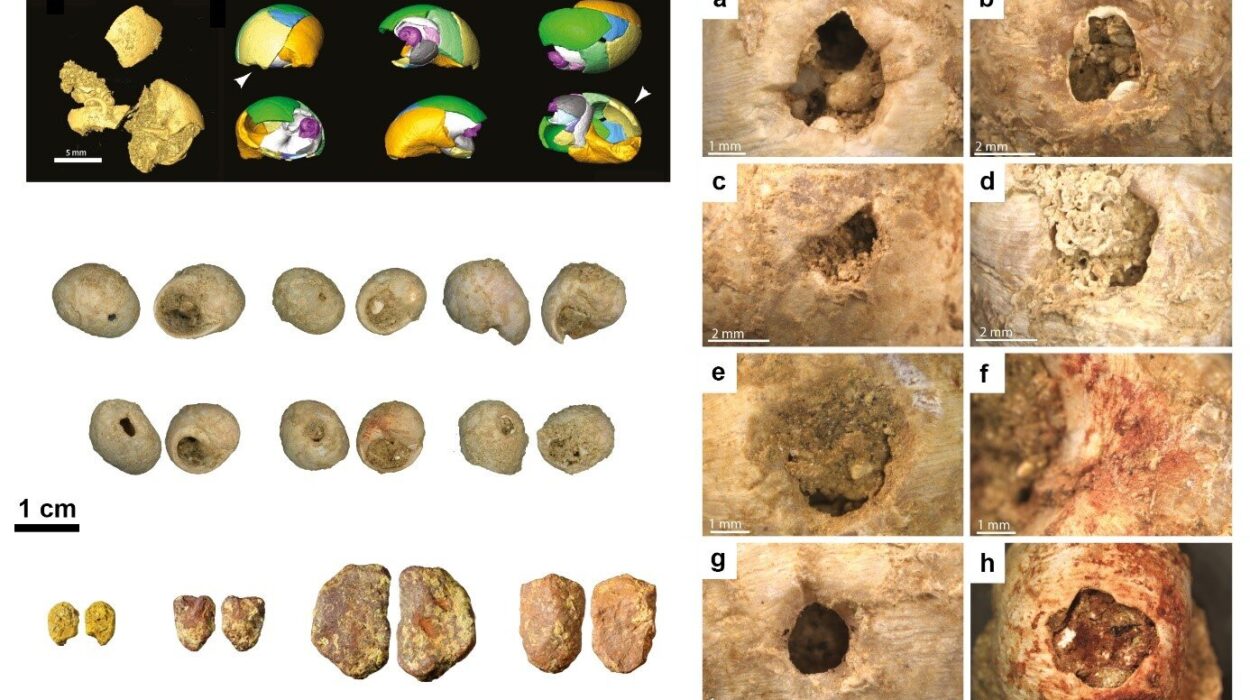

The study draws heavily on findings from the Lagash Archaeological Project, a collaboration led by Iraqi archaeologists and the Penn Museum. At this site, researchers combine ancient soil data, new environmental samples, and satellite imagery to reconstruct the vanished coastlines of Sumer.

What emerges is not a story of passive adaptation to geography but of active engagement with a landscape in flux. As Holly Pittman, director of the Lagash project, explains: “Rapid environmental change fostered inequality, political consolidation, and the ideologies of the world’s first urban society.”

The data reveal a striking truth: the world’s first cities were not built on stable ground but on a delta in constant transformation. Civilization itself was born out of humanity’s negotiation with instability.

Lessons for Today

Einstein once said that imagination is more important than knowledge, but in this case, imagination and science meet to reveal truths deeply relevant to our own world. The Sumerian story is not just about the past—it is a parable for the present.

Climate change today threatens to redraw coastlines, disrupt agriculture, and reshape societies. The Sumerians show us that environmental upheaval can be both destructive and creative. It can drive innovation, cooperation, and bold reinvention—but it can also produce inequality, conflict, and fragile dependence on complex systems.

As Giosan concludes, “Our work highlights both the opportunities and perils of social reinvention in the face of severe environmental crisis. Beyond this modern lesson, it is always surprising to find real history hidden in myth—and truly interdisciplinary research like ours can help uncover it.”

The Civilization That Water Built

The Sumerians called their land ki-en-gir, the “land of the noble lords.” Modern historians call it the cradle of civilization. But perhaps it is better understood as the land of water—the place where rivers, tides, and sediments conspired to shape the earliest cities.

The story of Sumer is not just about kings and temples, writing and wheels. It is about the ceaseless rhythm of tides, the restless shifting of a delta, and the human imagination that turned crisis into civilization. To understand the first cities, we must listen not only to the voices of clay tablets but also to the whispers of water that still echo beneath the Mesopotamian soil.

More information: Liviu Giosan et al, Morphodynamic Foundations of Sumer, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0329084