Around twelve thousand years ago, something extraordinary began to unfold across scattered pockets of the Earth. After hundreds of thousands of years of living as hunters and gatherers—following herds, foraging for berries, fishing rivers, and moving with the seasons—humans began to settle. They bent down, placed seeds into the soil, and waited. For the first time, people were not simply collecting what nature provided but actively reshaping the land to serve their needs. This moment marked the beginning of the Agricultural Revolution, a transformation so profound that it altered the trajectory of human history forever.

Without this turning point, there would be no villages, no cities, no written language, no kingdoms, and no modern world as we know it. The first farmers did not merely invent a new way of finding food—they unlocked the possibility of civilization itself. Yet, this revolution was not a sudden event, nor was it a simple story of progress. It was a long, complex, and often painful process filled with experiments, failures, adaptations, and consequences that continue to shape us today.

Life Before Farming: The World of Hunters and Gatherers

For the vast majority of our species’ existence, humans lived in small, mobile groups. Their survival depended on intimate knowledge of landscapes: where wild plants grew, when fruits ripened, how animals migrated, and which rivers teemed with fish.

Hunter-gatherer societies were incredibly adaptive. They used stone tools, crafted shelters, painted caves, and developed languages rich with meaning. Contrary to stereotypes, many lived relatively healthy lives. With diverse diets and active lifestyles, they often had fewer problems with obesity, cavities, or infectious diseases than later agricultural populations. They also worked fewer hours each week compared to farmers, leaving time for storytelling, rituals, and community bonding.

But hunting and gathering had limitations. Population growth was constrained by food availability and the need to remain mobile. As climates shifted after the last Ice Age, some regions saw wild resources dwindle, while others suddenly offered opportunities for experimentation with new food sources. It was in this shifting world that farming was born.

The Birth of Agriculture

The Agricultural Revolution, sometimes called the Neolithic Revolution, did not happen all at once or in one place. It emerged independently in several parts of the world, each cultivating different plants and animals suited to local environments.

In the Fertile Crescent—stretching across modern-day Iraq, Syria, Israel, and Turkey—wild wheat and barley grew abundantly, and herds of wild goats and sheep roamed. People here were among the first to deliberately sow seeds and domesticate animals. Archaeological evidence from sites like Jericho and Çatalhöyük reveals early farming communities that grew crops, stored food, and lived in permanent homes.

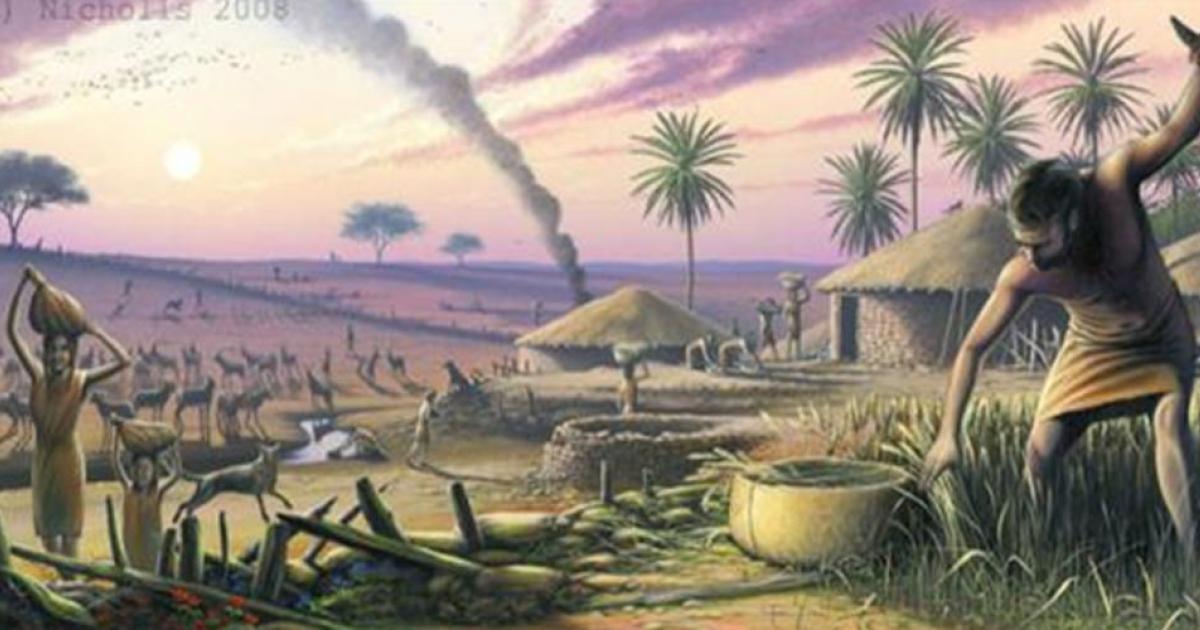

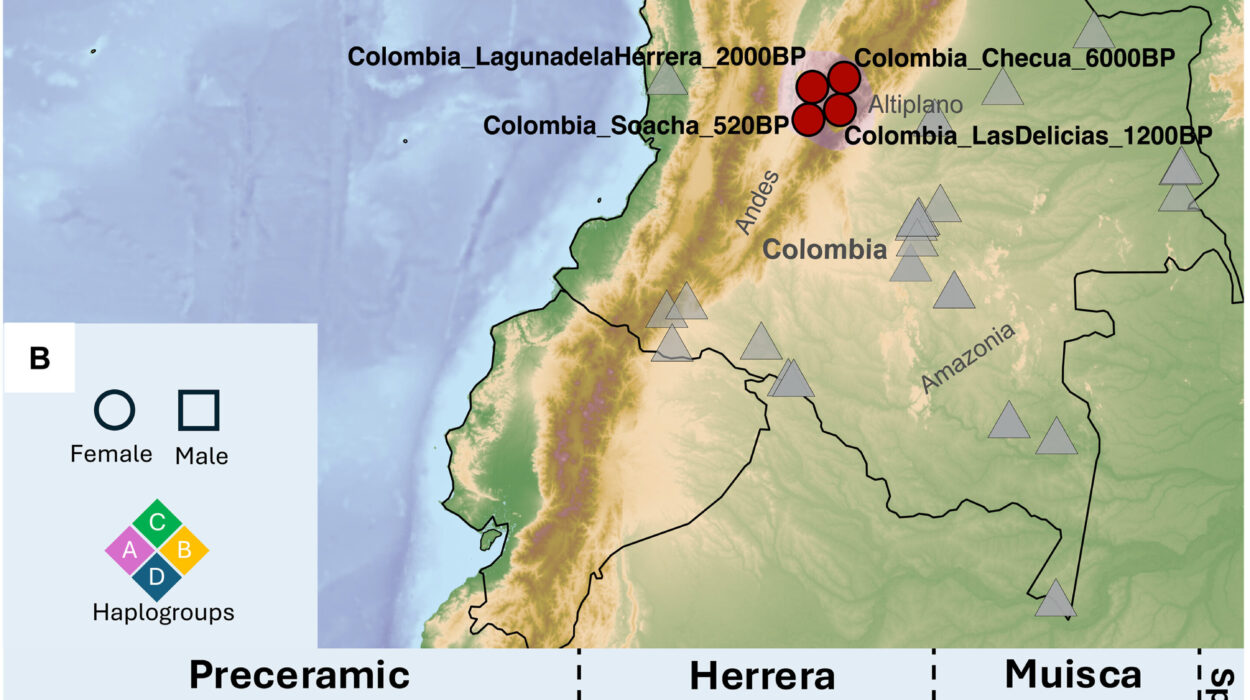

In China, rice and millet became staples. In Mesoamerica, maize, beans, and squash formed the foundation of diets. In the Andes, potatoes and quinoa were domesticated, alongside llamas and alpacas. In Africa, sorghum, millet, and yams were cultivated. Each center of domestication tells a parallel story: humans interacting with landscapes, experimenting with plants, and gradually transforming ecosystems.

The Domestication of Plants

Domestication was not an intentional, sudden invention but the result of countless small steps. Imagine a group of foragers collecting wild grains. They accidentally drop some near their camp. The next season, those grains sprout closer to home. People notice. Over time, they begin to scatter seeds deliberately.

Generation after generation, humans chose plants with desirable traits—bigger seeds, tastier fruits, shorter stalks, or less bitterness. Through this unconscious selection, plants evolved alongside humans. Wild teosinte, for example, bore small, hard kernels, barely resembling modern corn. Yet through thousands of years of selective planting, it transformed into maize—the golden crop that would sustain empires.

Domestication reshaped both species and landscapes. Forests were cleared, wetlands drained, and grasslands plowed. What had once been wild ecosystems gradually became fields and orchards—human-made environments designed for productivity.

The Domestication of Animals

Alongside plants, humans also domesticated animals, creating new relationships that went beyond hunting. The first domesticated species was the dog, long before farming began, valued for hunting assistance, companionship, and protection. With agriculture, new animals joined human settlements: goats, sheep, pigs, and cattle in the Near East; chickens in Southeast Asia; alpacas and llamas in South America.

Domestication altered animals profoundly. Wolves became docile dogs. Wild aurochs shrank into manageable cattle. Goats and sheep provided not only meat but also milk, wool, and hides. Animals became renewable resources rather than one-time kills.

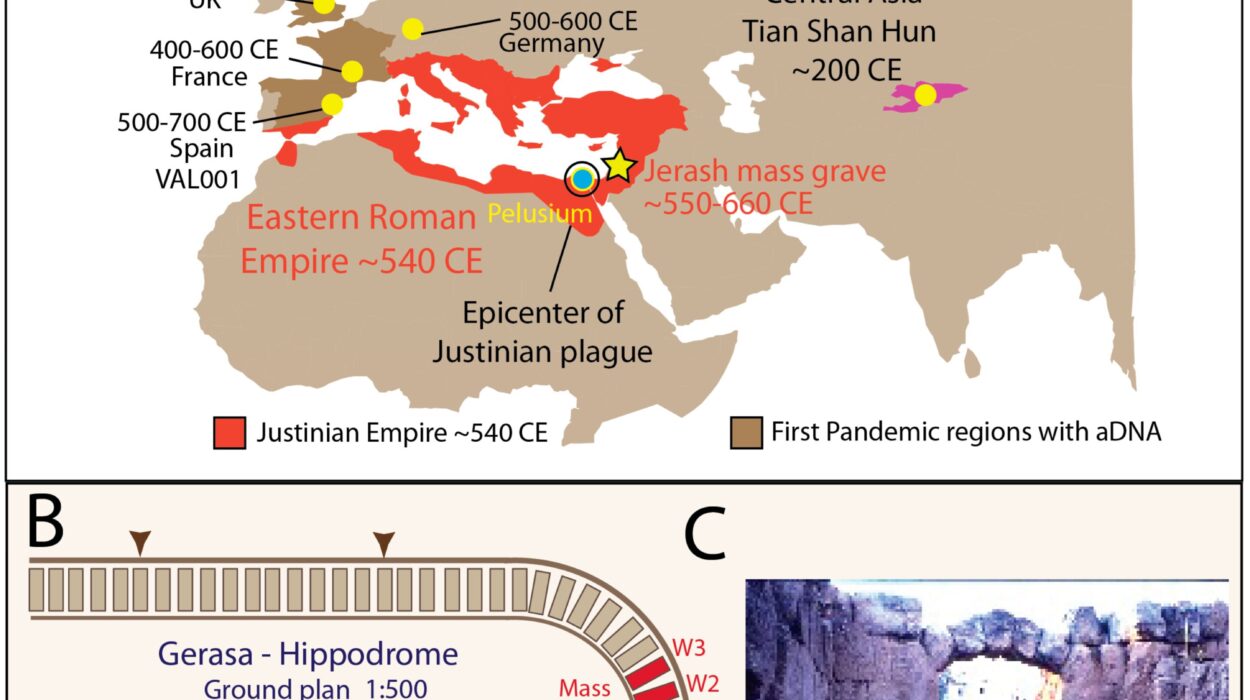

Yet, domestication also tethered humans to animals’ needs. Herds required grazing lands and protection. Diseases could jump from livestock to humans, leading to outbreaks that would devastate later civilizations. This shared destiny of humans and animals—called the “domestication syndrome”—was both a gift and a burden.

Settlements and the Rise of Villages

Once people began farming, they no longer needed to roam in search of food. Permanent settlements emerged, transforming social structures. Villages of mud-brick houses sprang up in fertile valleys, often near rivers that provided water for crops and transport routes for trade.

With stability came new inventions. Pottery allowed for storing grains and liquids. Grinding stones processed flour. Irrigation systems harnessed rivers to water fields. Farming communities grew, and populations expanded.

But with settled life came challenges. Food surpluses attracted thieves and rival groups, necessitating defenses and cooperation. Hierarchies formed as some individuals controlled resources. Inequality grew, laying the foundation for the social and political structures of later civilizations.

The Double-Edged Sword of Agriculture

While farming enabled larger populations and more complex societies, it also introduced hardships. Early farmers often worked longer hours than hunters and gatherers. Their diets, based heavily on a few crops, were less diverse and led to nutritional deficiencies. Skeletal remains from early agricultural sites reveal stunted growth, cavities, and signs of diseases spread in crowded villages.

Reliance on crops also made communities vulnerable. A failed harvest due to drought, pests, or floods could mean starvation. Dependence on animals exposed people to zoonotic diseases—illnesses transmitted from animals to humans—that would later fuel devastating epidemics.

Thus, the Agricultural Revolution was not a simple story of progress but a trade-off. It brought abundance and innovation, but also inequality, disease, and vulnerability. Humanity stepped onto a path that promised much but carried hidden costs.

Agriculture and the Birth of Civilization

Despite its drawbacks, farming fueled the rise of civilizations. Surpluses of food freed some people from agricultural labor, allowing them to specialize in crafts, trade, governance, or religion. This division of labor gave rise to artisans, priests, rulers, and eventually, empires.

The Fertile Crescent saw the emergence of Mesopotamian city-states like Uruk and Babylon, where temples and palaces rose above bustling markets. In the Nile Valley, Egypt’s pharaohs commanded a society sustained by the annual flooding of the river. In the Indus Valley, planned cities like Mohenjo-daro showcased advanced urban design.

Agriculture made possible writing, mathematics, and monumental architecture. Farmers’ harvests supported builders of pyramids, scribes who recorded laws, and armies that defended territories. The humble act of sowing seeds had blossomed into complex human societies.

The Spread of Farming

Farming did not stay confined to its birthplaces. Over centuries, agricultural practices spread, carried by migrating peoples and adopted by neighboring groups. Wheat and barley spread from the Fertile Crescent into Europe, transforming forests into fields. Rice agriculture spread through East and Southeast Asia. Maize crossed from Mesoamerica into North and South America, sustaining diverse cultures.

The spread was not uniform or uncontested. Some groups resisted farming, preferring the flexibility of hunting and gathering. Others blended strategies, practicing both foraging and cultivation. In many regions, the process unfolded over millennia, shaped by climate, geography, and cultural choices.

Agriculture’s Global Impact

The Agricultural Revolution reshaped not only human societies but also the planet itself. Forests were cleared on vast scales, altering ecosystems and driving extinctions. Rivers were diverted, soils plowed, and landscapes transformed into human-managed environments.

This process set the stage for what many scientists now call the Anthropocene—the age of humans as a dominant force shaping Earth’s systems. The first farmers, though unaware of it, began a process that continues today: the human-driven transformation of the planet.

The Psychological and Cultural Shifts

Agriculture also changed how humans thought about themselves and their place in the world. For hunter-gatherers, land was a shared space, moved through and respected. For farmers, land became property, to be owned, divided, and defended. Concepts of wealth and inheritance took root, leading to new social dynamics and conflicts.

Religions, too, reflected agricultural life. Fertility gods, harvest rituals, and seasonal festivals emerged. Myths spoke of cycles of planting and rebirth, mirroring the rhythms of farming. The soil was not just dirt—it was sacred, the giver of life.

Lessons from the First Farmers

Looking back, the story of the first farmers is both inspiring and cautionary. It reminds us of human ingenuity—the ability to transform wild plants and animals into partners in survival. It shows our adaptability, creativity, and determination. But it also warns of unintended consequences: disease, inequality, environmental degradation, and dependence on fragile systems.

Today, as modern agriculture feeds billions, we still grapple with the same challenges the first farmers faced: how to produce enough food sustainably, how to protect against crop failures, and how to balance human needs with the health of the planet.

The Long Legacy

The Agricultural Revolution was not a single event but a turning point that set humanity on a new course. From scattered experiments with wild grains to the rise of mighty civilizations, the first farmers planted not only crops but also the seeds of the modern world.

Their legacy is visible in every loaf of bread, every field of rice, every vineyard, and every orchard. The echoes of their choices shape our diets, our landscapes, our economies, and our societies.

To understand the first farmers is to understand ourselves—not just where we came from, but where we are heading. The story of agriculture is the story of humanity: our brilliance, our struggles, and our unending quest to shape the world around us.