Long before the sweep of modern highways carved across the Arabian Peninsula, before the kingdoms and caravan routes of history etched themselves into the landscape, humans walked a world that was both harsh and alive with possibility. Arabia, often portrayed as an eternal desert, has long concealed more than it revealed. But now, from the shadowy depths of ancient caves and lava tubes, whispers of a forgotten human past are rising again—reminding us that even the most forbidding terrain can cradle vibrant lives and forgotten stories.

The Umm Jirsan lava tube in northern Saudi Arabia is one such place. To the untrained eye, it may appear barren, a collapsed scar in the landscape. But beneath its surface lies one of the most astonishing archaeological records ever unearthed in Arabia—evidence of life, movement, adaptation, and community stretching back nearly 10,000 years. Thanks to a collaborative effort led by Griffith University’s Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution (ARCHE) and a global team of scientists, we are now witnessing a revolution in our understanding of Arabia’s prehistoric inhabitants.

Lava Tubes, Living Memory

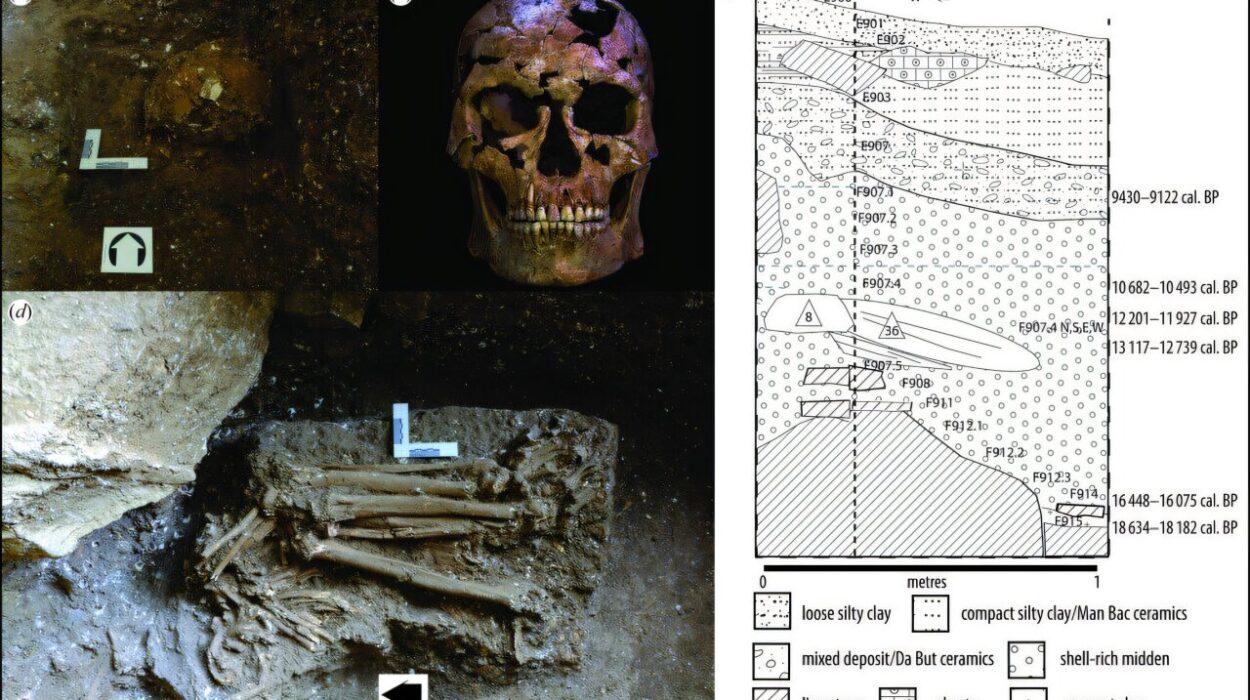

Caves and lava tubes are strange places to search for the traces of ancient life. They are dark, remote, and often overlooked in traditional surveys. But that is exactly why they matter. Unlike exposed open-air sites, these underground sanctuaries can act as natural time capsules—shielding fragile remains from erosion, wind, and sun. In Arabia, where organic material usually decays rapidly under searing heat and dry winds, caves like Umm Jirsan offer archaeologists a rare gift: preservation.

Inside these basaltic tunnels, researchers discovered not just bones and tools, but a broader narrative of human life unfolding across millennia. Layers of charcoal, sediment, rock art, and faunal remains tell a tale of persistence, change, and adaptation in a shifting landscape. Here, archaeological evidence stretches from the Neolithic through the Chalcolithic and into the Bronze Age, a time span that encompasses vast technological, environmental, and social transitions.

“This site likely served as a crucial waypoint along pastoral routes, linking key oases and facilitating cultural exchange and trade,” explains Dr. Mathew Stewart, lead researcher and ARCHE Fellow. “Our findings at Umm Jirsan provide a rare glimpse into the lives of ancient peoples in Arabia.”

Traces of Pastoral Life in a Sea of Stone

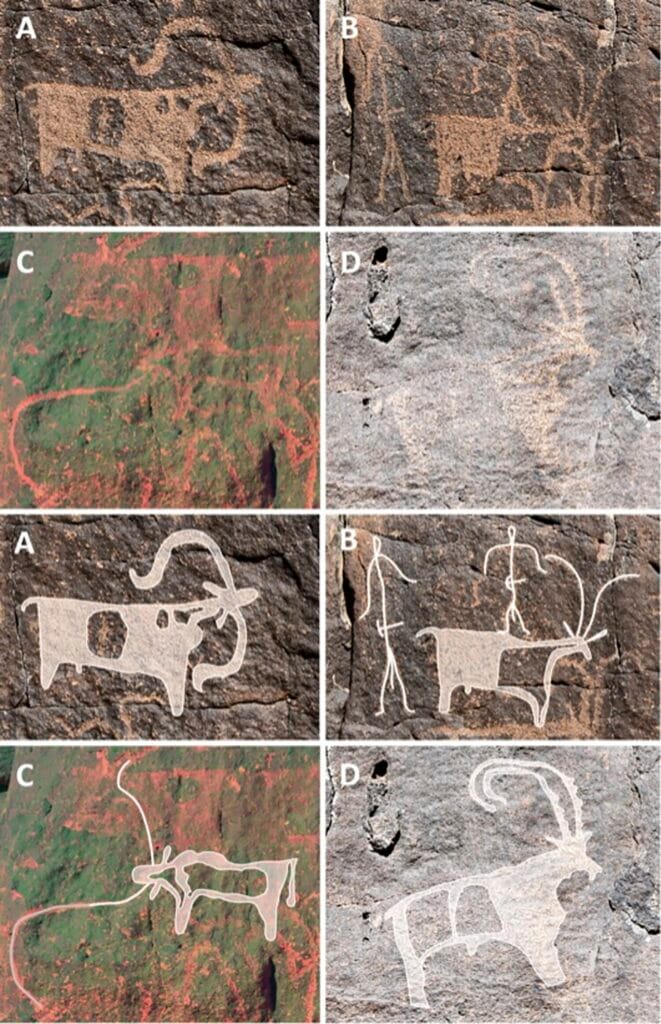

Perhaps most striking in the Umm Jirsan findings is the portrait they paint of early pastoral societies—groups of people who lived not only with the land but moved across it in complex, organized ways. Herds of cattle, sheep, goats, and even dogs left their marks not only in the bones scattered across the lava floor but in the art etched into the walls.

Petroglyphs—carefully pecked images of horned cattle, flocks, and human figures—adorn the surrounding rock surfaces like ancient journal entries. These are not random doodles but intentional records of lifeways. They tell us what animals mattered. They hint at rituals, gatherings, the movement of herds through seasonal rhythms. The scenes evoke moments of care and control, of human-animal relationships that were economic, emotional, and deeply embedded in survival.

Faunal remains recovered at the site corroborate this picture. Isotopic analysis of animal bones reveals that livestock grazed on wild grasses and shrubs—vegetation that fluctuated with rainfall and season, requiring knowledge of landscape patterns and flexible movement. These weren’t static settlements but communities organized around mobility, memory, and ecological knowledge.

Protein and Plants: A Changing Human Diet

The remains of the animals themselves offer more than just insight into herding. They also speak to human diets and dietary changes over time—shifts that reflect broader transformations in society and environment.

Chemical signatures preserved in the bones tell a nutritional story. Early inhabitants of Umm Jirsan consumed a protein-rich diet, likely based on meat and possibly dairy. But over time, there is a clear uptick in the consumption of C3 plants—plants typically found in wetter, cultivated environments like oases. This dietary shift is subtle but profound. It suggests the emergence of oasis agriculture, an early flirtation with domesticated plant use in an otherwise nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyle.

The implications are enormous. It means that even in an environment as harsh and changeable as northern Arabia, ancient peoples weren’t just reacting to nature—they were reshaping it, nurturing it, coaxing it to provide. They were engineers of their own resilience.

Science in the Shadows: A New Kind of Archaeology

What makes the discoveries at Umm Jirsan truly transformative isn’t just the findings themselves—it’s how they were found. The interdisciplinary approach taken by the researchers, combining archaeological excavation, geochemical analysis, paleoecology, and rock art interpretation, demonstrates the power of science that crosses boundaries.

“This represents the first comprehensive archaeological study of a lava tube in Saudi Arabia,” says Professor Michael Petraglia, Director of ARCHE. “Underground localities are globally significant in archaeology and Quaternary science, and our work shows their immense potential for unlocking Arabia’s ancient past.”

This study was no solo act. It involved close coordination with Saudi Arabia’s Heritage Commission, Ministry of Culture, and Geological Survey. Researchers from King Saud University worked alongside experts from the UK, US, and Germany. It is a model of modern archaeological research: inclusive, multidisciplinary, and rooted in respect for local heritage.

In the process, it is not just ancient stories being told—it is the future of archaeological inquiry that is being reshaped.

A Dynamic Landscape, A Dynamic People

Arabia has long been viewed as a kind of empty corridor—a place through which early humans passed but never truly stayed. That view is crumbling. The discoveries at Umm Jirsan and other nearby sites challenge this perception, showing that Arabia was not a desert to be crossed, but a homeland to be lived in.

Climatic data show that Arabia’s past climate was not always as arid as it is today. Periods of increased rainfall created “green windows” in which lakes, grasslands, and wildlife flourished. It was during these times that human populations expanded, adapted, and innovated. When the rains retreated, so did the lakes—but the people found ways to endure.

The story of Umm Jirsan is, at heart, a story of adaptation. It reveals humans not as victims of their environment, but as students of it—learning its rhythms, mastering its opportunities, surviving its extremes. This is a tale not only of survival, but of imagination.

Toward a Fuller Human Story

The deeper archaeologists dig in Arabia, the more they uncover not just bones and tools, but evidence of creativity, connection, and cultural exchange. The region’s lava tubes and caves are proving to be more than physical spaces—they are memory vaults, repositories of human innovation that have lain dormant under the sand.

These discoveries matter far beyond the academic realm. They reshape how we understand our species. They challenge narratives of European centrality in prehistory and elevate Arabia to a place of rich complexity and central importance. The past was not built in one place; it was woven from many. Arabia is part of that weave.

As research continues, more secrets are sure to emerge—from Umm Jirsan and beyond. Each artifact, each layer of soil, each etched figure in stone, brings us one step closer to understanding not only who ancient Arabians were, but who we are as a species—how we move, how we change, and how we remember.

Reference: First evidence for human occupation of a lava tube in Arabia: The archaeology ofUmm Jirsan Cave and its surroundings, northern Saudi Arabia, PLoS ONE (2024). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0299292