Around 9,000 years ago, Europe stood on the threshold of transformation. For countless generations, its inhabitants had lived as hunter-gatherers—roaming forests, rivers, and plains, surviving through fishing, hunting, and foraging. Then came the farmers. Migrating from the Aegean and western Anatolia, they carried with them a way of life that would permanently reshape human existence: agriculture.

This shift was not sudden. For a time, two worlds—one rooted in mobility and wild landscapes, the other in settled fields and cultivated crops—coexisted. It was in this encounter, where foragers and farmers met, traded, mingled, and sometimes intermarried, that the seeds of Europe’s future were planted.

The Danube Route: A Corridor of Change

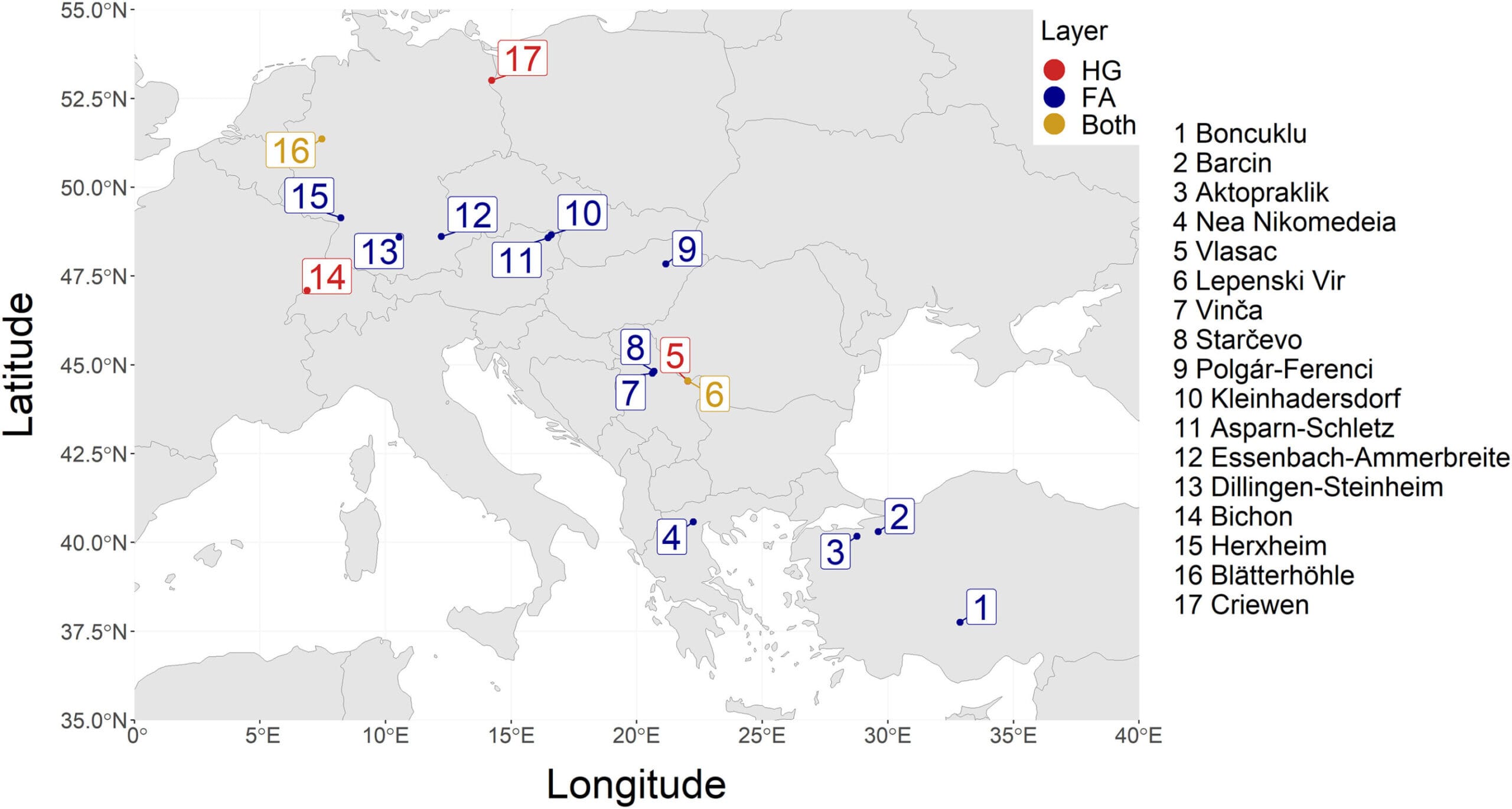

The farmers’ journey was not random. Archaeological and genetic evidence shows that many followed what scientists call the Danube route, moving along rivers and fertile valleys that offered both water and land for cultivation. From Anatolia, they moved northward into the Balkans, across the Carpathians, and eventually into Central Europe, reaching areas of present-day Germany.

But along this route, they were never alone. Indigenous hunter-gatherer communities already thrived in these regions. For generations, these groups and the newcomers lived side by side. Their interaction was far more complex than a simple story of one population replacing another.

Was It Conquest or Coexistence?

For decades, scholars debated the nature of this great transition. Did farming spread mainly through cultural diffusion—hunter-gatherers simply learning new techniques from their neighbors? Or did it spread through demographic expansion—migrating farmers settling, marrying, and mixing with local groups?

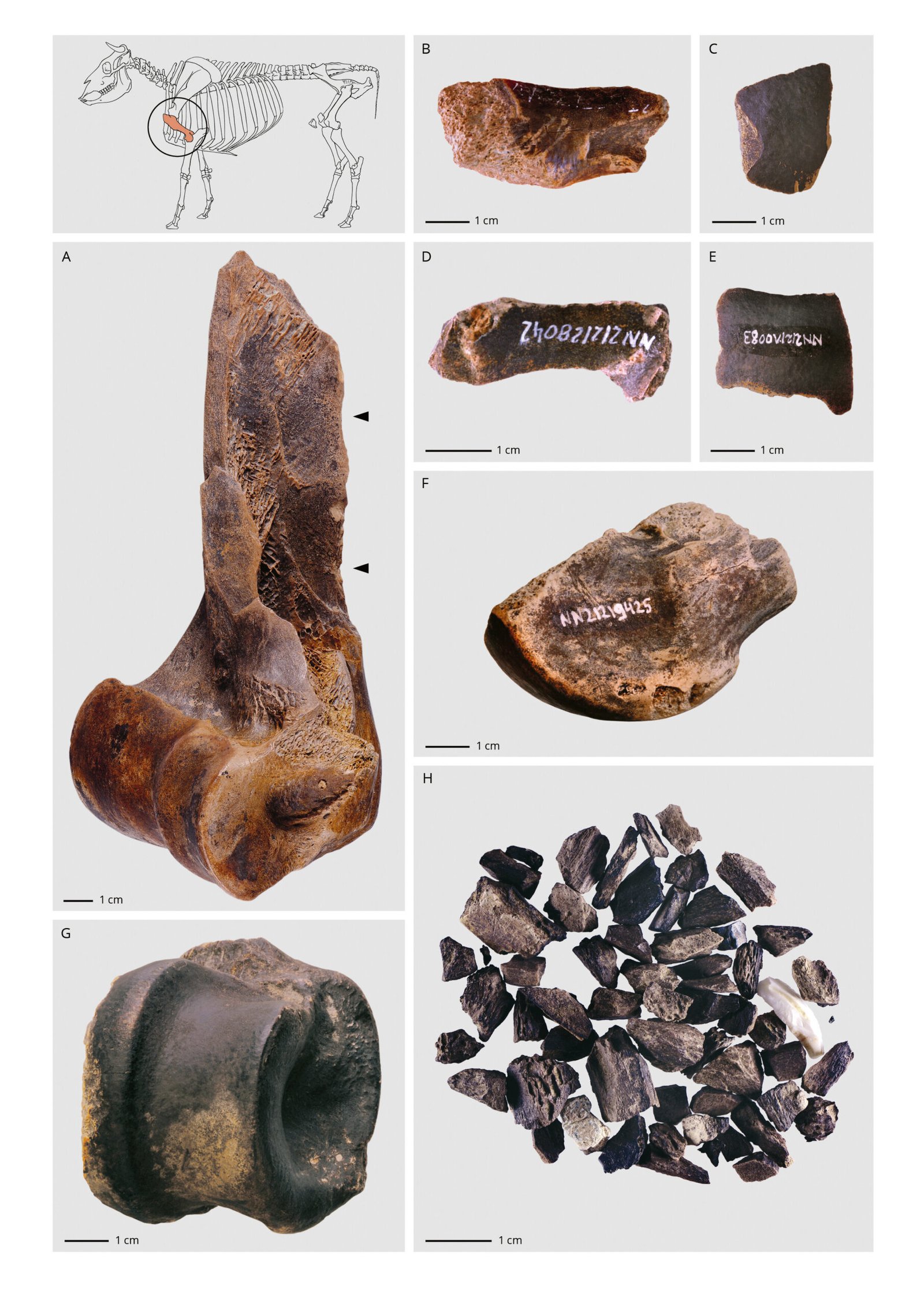

The archaeological record offered hints: stone tools, pottery, and dwellings showing traces of both traditions. But it was the rise of paleogenomics—the study of ancient DNA—that provided the clearest answers. By analyzing human remains thousands of years old, scientists discovered undeniable genetic signatures of both populations. The transition was not just about ideas spreading—it was about people meeting, living together, and reshaping each other’s communities.

Simulating Encounters Between Two Worlds

A recent study, published in Science Advances and led by researchers at the University of Geneva (UNIGE) in collaboration with the University of Fribourg and Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, has added a new layer of understanding.

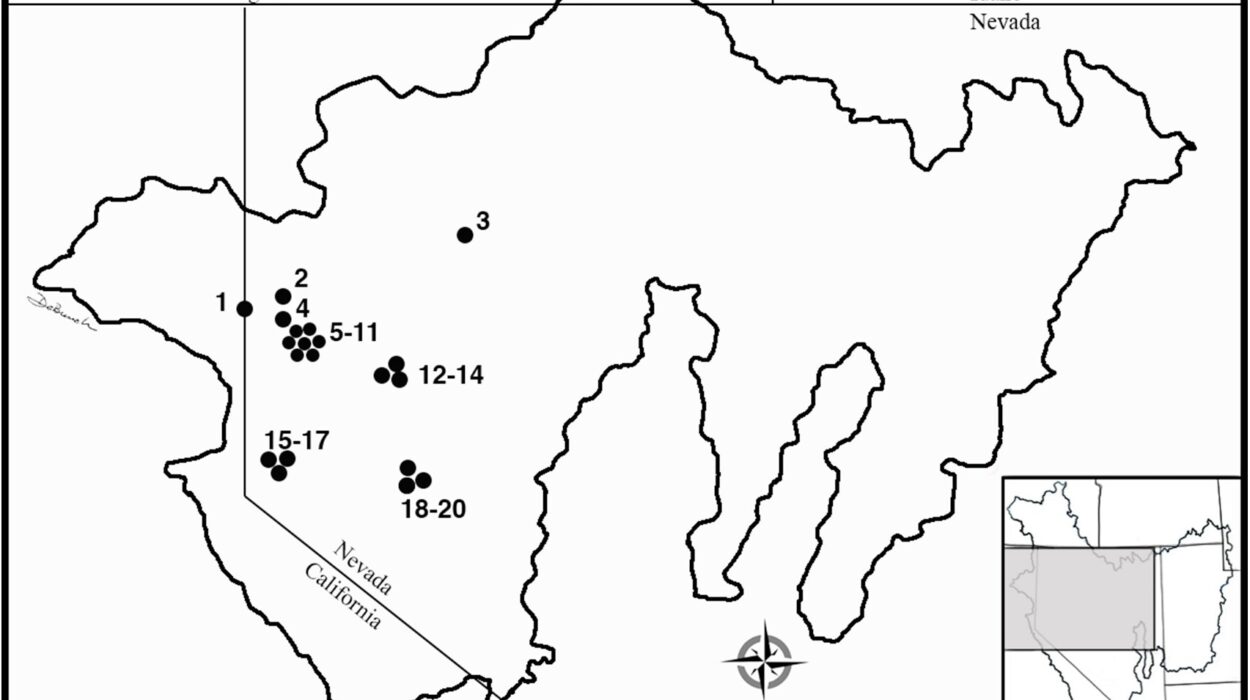

The team combined ancient DNA with computer simulations to reconstruct how these encounters unfolded along the Danube route. Their models included geography, population size, birth rates, and even the probabilities of intermarriage. By comparing thousands of simulated outcomes with real genetic data from 67 prehistoric individuals, they could test which scenarios most closely mirrored reality.

The results revealed a fascinating pattern: when farmers first entered new regions, genetic mixing with hunter-gatherers was minimal. But over time, as the two groups lived side by side, the level of interbreeding grew. Far from being a story of immediate replacement or violent conquest, the Neolithic transition appears to have been a process of gradual and increasing integration.

The Strength of Numbers and Mobility

The study also shed light on why farmers eventually prevailed. Their population size was about five times larger than that of the hunter-gatherers. With more people, more children, and more stable food supplies, the farming communities had a demographic advantage that hunter-gatherers could not match.

Yet expansion was not only slow and steady. The models suggest that sometimes, small groups of farmers made bold “migration jumps”, traveling far beyond the previous frontier of settlement. These leaps helped speed up the spread of agriculture deep into Europe, creating islands of farming life that later connected with each other.

Blending, Not Erasing, Histories

Perhaps the most striking insight from the study is the emphasis on coexistence. The Neolithic revolution in Europe was not the simple triumph of one way of life over another. Instead, it was a long, messy, human process. For generations, hunter-gatherers and farmers exchanged not just goods and tools but also genes, traditions, and ways of thinking.

This blending left a permanent mark. Modern Europeans carry in their DNA the traces of both groups. The legacy of hunter-gatherer endurance and farmer innovation is written into the genetic fabric of today’s populations.

A New Way of Seeing the Past

By bringing together archaeology, genetics, and computer modeling, the Geneva team has provided one of the most detailed pictures yet of this pivotal era. Their findings remind us that history is rarely a story of sharp divides. More often, it is a story of contact zones—frontiers where people meet, negotiate, compete, and ultimately shape each other’s futures.

The Neolithic transition was one such frontier, and its echoes still resonate today. The very landscapes of Europe, with their farms, villages, and towns, are the descendants of those first encounters along the Danube.

Why This Story Matters Today

It is tempting to view the Neolithic revolution as distant, locked away in the mists of prehistory. Yet its themes are timeless. Migration, cultural exchange, coexistence, and identity are issues that remain at the heart of human societies. Understanding how our ancestors navigated these challenges does more than explain the past—it offers perspective on our present.

The story of Europe’s first farmers and hunter-gatherers is not just a tale of survival and adaptation. It is a reminder that human history is built on contact, cooperation, and shared transformation. In the end, it was not confrontation that defined this great transition, but the ability of different worlds to come together and create something new.

More information: Alexandros Tsoupas et al, Local increases in admixture with hunter-gatherers followed the initial expansion of Neolithic farmers across continental Europe, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adq9976