For decades, archaeologists have tried to reconstruct one of prehistory’s most consequential journeys — the eastward spread of Neanderthals from Europe into Asia in the tense twilight before their disappearance. This was the period when the world shifted from a multi-species landscape to one dominated by Homo sapiens. It is a narrative with many gaps: bones rot, DNA degrades, and migration leaves no footprints in stone. But a recent discovery from the Crimean Peninsula has supplied something that has been missing — genetic proof that links European Neanderthals to their Asian cousins.

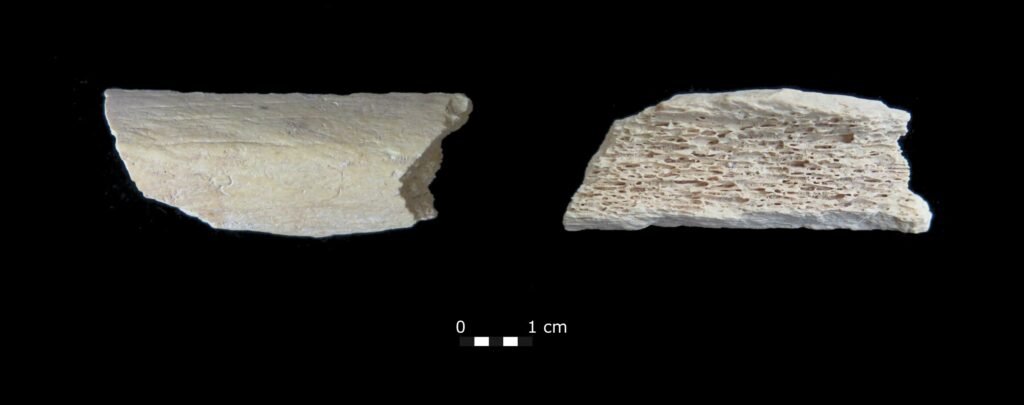

At the Starosele cave site in Crimea, researchers re-examined 150 scraps of bone left in layers of earth long known to have been associated with Neanderthal activity. Most of these fragments were too small or too damaged to identify. But one fragment — so nondescript it could have been discarded — held secrets. Using a method called collagen peptide mass fingerprinting (ZooMS), researchers confirmed the fragment belonged to a hominin. Then, with great care, they extracted DNA.

The radiocarbon clock placed this individual, now nicknamed “Star 1,” at roughly 45,000 years old — almost exactly when Neanderthals were vanishing from the fossil record in Europe.

The Diet of a Vanished People

Before the DNA was even analyzed, the bone assemblage told a parallel story — one of survival strategy. Ninety-three percent of the bones recovered and identified belonged to horses. This is not coincidence. It shows that Neanderthals at Starosele were specialized hunters, targeting horses as their primary prey. Other animals like bison, wolves, and even rhinoceros were present only in trace amounts.

The image that emerges is not of desperate scavengers but of capable, coordinated hunters who repeatedly returned to the same region and exploited a rich food source. Starosele was not a camp of wanderers passing through — it was a site of planned subsistence.

A Genetic Bridge Between Two Worlds

Using mitochondrial DNA — a form of genetic material passed down through maternal lines — scientists confirmed Star 1 as a Neanderthal. But more importantly, the genetic signature did not fully match known European Neanderthals. Instead, Star 1 showed a mixture of similarity and distance: positioned “basal” to some European Neanderthals, but genetically “derived” relative to Siberian ones.

When the genetic data were compared broadly, Star 1 showed the strongest similarity to Neanderthals found thousands of kilometers away in the Altai region of Siberia — individuals from Denisova Cave, Chagyrskaya Cave, and Okladnikov Cave. These caves sit 3,000 kilometers east of Crimea, yet the DNA suggests that populations in far Asia and those in the western edge of Europe were not isolated worlds. They shared ancestry — and perhaps connection.

This link was reinforced by artifacts. Stone tools recovered at Starosele resemble those found in the Altai region, implying cultural ties or shared technological traditions — the signatures of human interaction, whether through migration, intermarriage, or long-range drift of knowledge.

Reconstructing the Road: How Neanderthals May Have Moved East

To imagine the route Neanderthals might have taken, researchers brought paleoclimate science into the picture. They modeled prehistoric habitats using ancient climate data and searched for corridors that would have been favorable for migration. One such corridor emerged along roughly 55°N latitude — a route that would have been environmentally stable and passable between 120,000 and 100,000 years ago, and again perhaps around 60,000 years ago.

This climatic “window” could have allowed Neanderthals to move — not in a single migration wave, but over many thousands of years, across plains and steppes from Europe toward central Asia. Such corridors would have been bridges not just of movement but of culture — the highways of information transfer long before writing, farming, or cities.

Why One Bone Matters

The Star 1 fragment is small — nothing like the intact skulls or skeletons that anthropologists dream of. Its DNA is incomplete. It cannot resolve every branch on the Neanderthal family tree. Yet its significance is large precisely because evidence of this kind is so rare. In the absence of well-preserved remains, even partial sequences can shift a narrative.

This single bone confirms that the Neanderthals who once lived in Crimea were not biologically isolated from their counterparts in Asia, but were part of a broader population system spanning continents. It hints that Crimean Neanderthals may have been participants — or descendants of participants — in deep-time migrations that crossed Eurasia before humans like us took the stage.

Completing a Story That Is Still Being Written

The find at Starosele does not close the book on Neanderthal dispersal. Instead, it adds another piece to a puzzle whose edges are still emerging. It supports a view of the Neanderthal world as dynamic, mobile, and interactive — not as a local culture fading into extinction, but as a widespread species whose roots reached from the Atlantic margins of Europe toward the mountains of central Asia.

To understand their disappearance, we must first understand their lives: what they ate, how they moved, whom they shared genes and technology with. Star 1 — a single bone from a collapsed cave — brings us closer to that understanding. In telling the story of one Neanderthal, it reminds us that the traces of ancient lives continue to speak, even when all that remains is a sliver of bone and the patience to read what it still holds.

More information: Emily M. Pigott et al, A new late Neanderthal from Crimea reveals long-distance connections across Eurasia, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2518974122