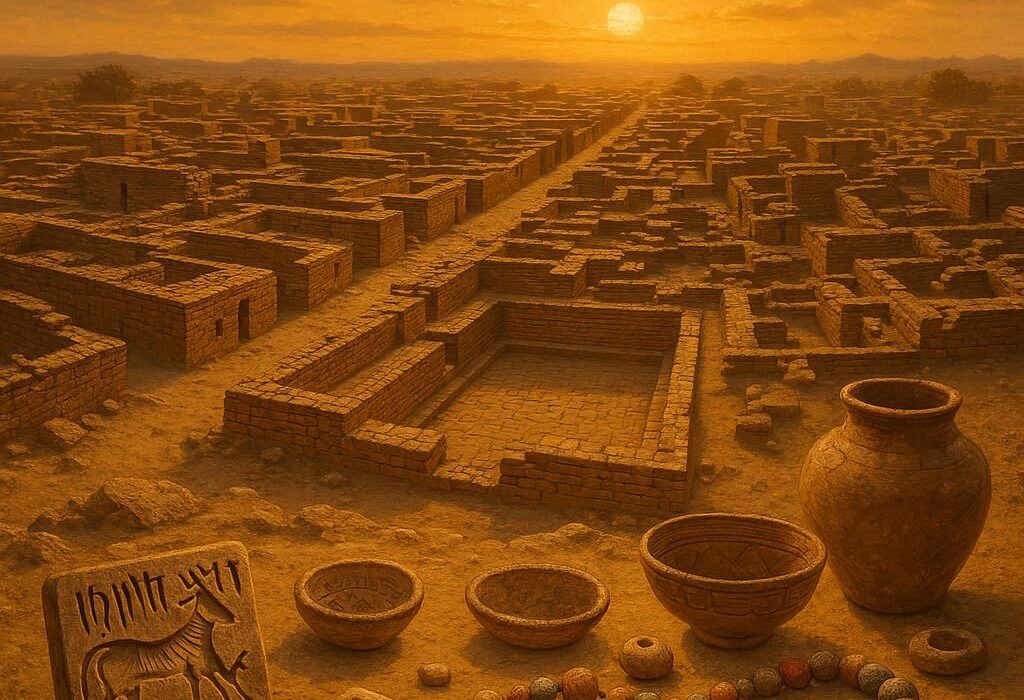

Roughly 10,000 years ago, something extraordinary began to reshape the human experience forever. In a sweeping transformation that would change everything from diet to destiny, small bands of hunter-gatherers began settling down, planting crops, domesticating animals, and building the world’s first permanent villages. This moment—what we call the Neolithic Revolution—marked the birth of agriculture and sedentary life.

But while we’ve long known where this new way of life began—the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East—the mystery of how it spread into Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) and onward to Europe has remained a puzzle. Did farming and village life arrive with migrating peoples? Or did local hunter-gatherers simply adopt new ideas from their neighbors?

Now, a groundbreaking study published in Science offers a more nuanced answer. Led by a Turkish-Swiss team of geneticists and archaeologists, the research combines ancient DNA and archaeological data in an unprecedented way. The result? A sweeping but surprisingly human portrait of how people in Anatolia transitioned into a new era—not through invasion or replacement, but often through quiet adaptation, local evolution, and the power of ideas.

The Bones That Speak Across Millennia

For years, archaeologists have pieced together the Neolithic transition using artifacts—pottery shards, stone tools, remnants of homes. But artifacts alone don’t reveal the full story of who used them or how they lived. That’s why the team, led by scientists from Middle East Technical University (METU), Hacettepe University in Ankara, and the University of Lausanne (UNIL), turned to ancient genomes for deeper insight.

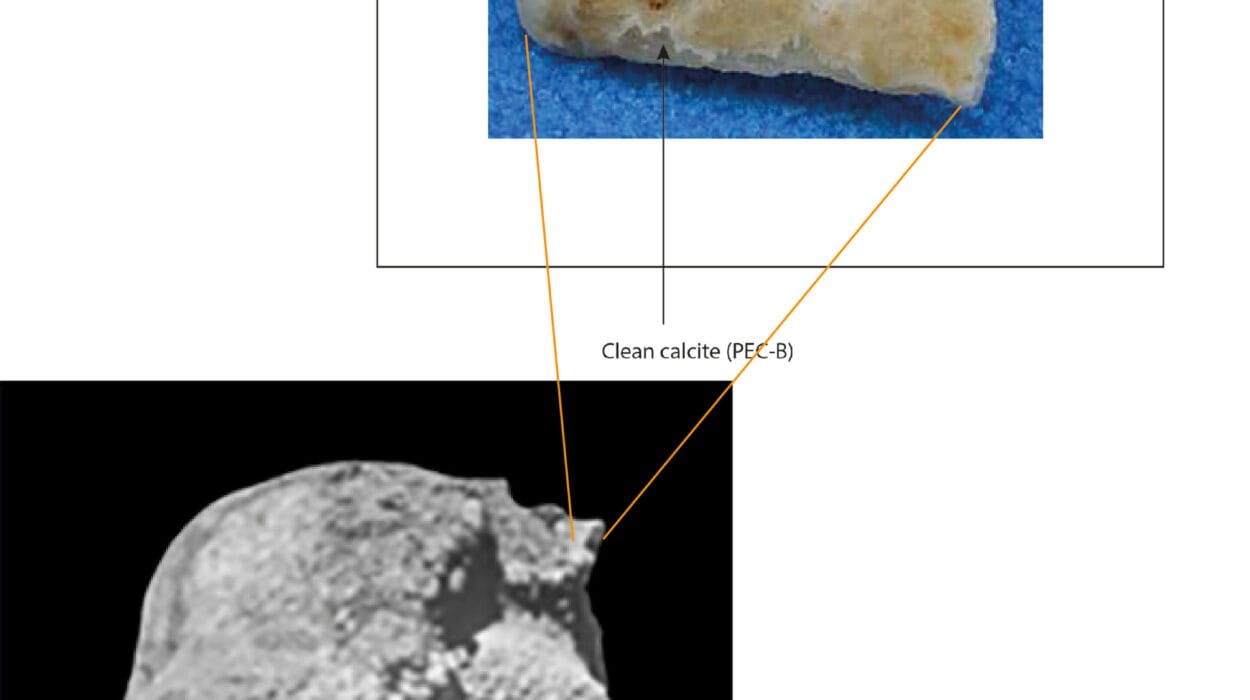

Sequencing the genome of a 9,000-year-old individual from West Anatolia—the oldest yet recovered in the region—the researchers found something unexpected: genetic continuity. In other words, these early farmers weren’t newcomers. They were locals. For thousands of years, the population in this part of Anatolia remained largely stable—even as their tools, homes, and rituals changed dramatically.

“In some regions of West Anatolia, we see the first transitions to village life nearly 10,000 years ago,” explained Dilek Koptekin, the study’s first author. “Yet we also observe thousands of years of genetic continuity. That means populations did not migrate or mix massively, even though cultural transition was definitely happening.”

A Missing Chapter in the Neolithic Story

Until now, most narratives about the spread of farming focused on later events—especially the wave of Neolithic migrants that moved into Europe after 6,000 BCE. But what happened before that, especially in the heartland of Anatolia, had remained murky. How did communities shift from caves to settlements, from wild food to cultivated crops, from stone spears to ceramics and architecture?

“Our study allows us to go back in time—to events that were mainly a matter of speculation up to now,” said Koptekin.

The team sequenced 29 new ancient genomes from Anatolia and the surrounding regions, pairing them with previously published data to create a genetic map that spans seven millennia. Their results offer a new kind of clarity: while cultural shifts were widespread and rapid, they often occurred without corresponding changes in the population’s genetic makeup.

“Genetically speaking, these people were mainly locals,” said Anna-Sapfo Malaspinas, a computational biologist at UNIL. “Yet their material culture evolved rapidly. This suggests they adopted Neolithic practices by cultural exchange rather than population replacement.”

Quantifying the Unseen

To strengthen the connection between biology and culture, the researchers did something no one had done at this scale before: they quantified archaeological data.

Archaeologist Çiğdem Atakuman from METU helped lead the effort, which involved combing through hundreds of archaeological reports and assigning numerical values to traits like pottery styles, architecture, and tools. Then they compared these cultural profiles with the genetic information of individuals buried at the same sites.

“By giving quantitative values to the archaeological data, we were able to directly compare large amounts of data across different sites for the first time,” Atakuman explained.

This method allowed the team to trace not just who moved where, but how ideas moved—how farming techniques, domestic tools, and architectural knowledge spread from one community to another, even in the absence of large-scale migration.

The Neolithic Mosaic: Movement Without Mass Migration

The findings overturn the idea that new tools or objects in the archaeological record must always signal the arrival of new people.

“Archaeologists have this proverb, ‘Pots don’t equal people,’” Koptekin noted. “Our study confirms this notion.”

But that doesn’t mean population movements didn’t happen at all. In some parts of Anatolia—particularly around 7,000 BCE—the team detected evidence of real demographic change. Here, new groups arrived, and the genetic signatures shifted. These newcomers brought both different DNA and new cultural practices.

In the Aegean region, too, later migrations introduced innovations that would ripple westward into Europe. But even these migrations, the team found, made up only a small fraction of the overall Neolithic transformation.

“The Neolithic, in this view, was not a single process,” said Füsun Özer from Hacettepe University. “It was a patchwork of transformations, combining cultural adoption, mobility, and at times, migration.”

Change Doesn’t Always Mean Crisis

Perhaps one of the most fascinating implications of the study is psychological: it challenges the idea that humans only change in response to disaster, invasion, or environmental crisis.

“Humans have always been adaptive and inclined to change their way of living,” Koptekin observed. “We don’t need crises or big migration events to bring about change.”

This echoes across time to today’s world, where we often think of progress as something imposed by necessity. Instead, the Neolithic transition shows that humans, when exposed to new ideas, are remarkably open to innovation—even if they don’t move very far to embrace it.

Science From the Source

This ambitious project wasn’t driven by a distant institution looking into Anatolia from afar. It was conceptualized and led primarily by researchers in Turkey—scholars working in the very landscape they were studying.

For Malaspinas, this was more than a scientific advantage—it was a model for how research should work in the future.

“Our collaboration shows how we, as a scientific community, should move forward to create a more inclusive and globally balanced research landscape,” she said.

The study also demonstrates the power of combining disciplines that don’t always speak the same language. By blending genetics and archaeology—and backing that with meticulous data analysis—the team created a new template for understanding prehistory.

Beyond the Model: A New Vision of the Past

The Neolithic transition in Anatolia, it turns out, wasn’t a one-size-fits-all revolution. It was a rich mosaic of local continuity and occasional change. It was a story of ideas moving further and faster than the people who first imagined them.

It’s a story of caves slowly giving way to homes, of rituals spreading along unseen routes, of farming knowledge passed hand to hand. And it’s a reminder that behind every ancient tool, every genome, every pottery shard, were human beings not so different from us—curious, experimental, and endlessly adaptive.

Thanks to this innovative study, we no longer have to guess at how the Neolithic spread across Anatolia. We can now trace it, layer by layer, genome by genome, and idea by idea.

Reference: Dilek Koptekin et al, Out-of-Anatolia: cultural and genetic interactions during the Neolithic expansion in the Aegean, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adr3326. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adr3326