In the late 1930s, during an excavation near Baghdad, a peculiar artifact emerged from the soil. It was unassuming at first glance: a small clay jar, about the size of a fist, sealed with asphalt, containing a copper cylinder and an iron rod. Nothing about its appearance screamed “technological marvel,” yet this little object would go on to spark one of the most intriguing debates in archaeology. Could this humble jar, now famously known as the “Baghdad Battery,” be evidence of electricity in the ancient world—long before Benjamin Franklin flew his kite, or Thomas Edison lit his first bulb?

The story of the Baghdad Battery has gripped scientists, dreamers, and conspiracy theorists alike. It is a tale where archaeology collides with imagination, where ancient craftsmanship brushes against the edges of modern science. But as fascinating as the theories are, the truth is far subtler, though no less captivating. To truly understand this enigmatic object, we must journey into the world of ancient Mesopotamia, step into the minds of its discoverers, and sift through decades of speculation and evidence.

The Unearthing of an Enigma

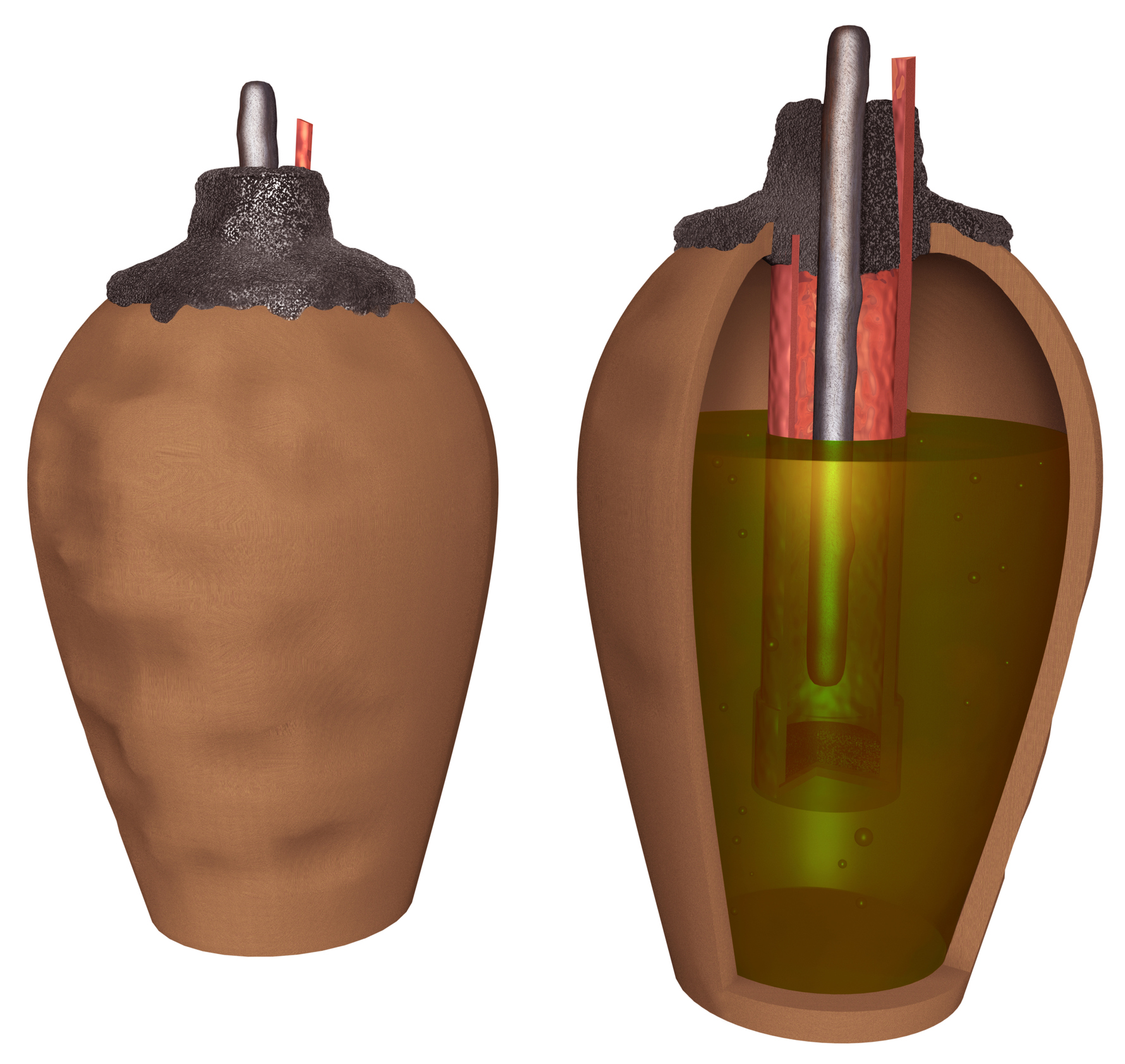

The year was 1938, and Wilhelm König, a German archaeologist working in Iraq, stumbled upon a collection of clay jars in the National Museum of Iraq. These jars, about 13 centimeters tall, each contained a tightly rolled copper sheet, which encased an iron rod. The copper cylinder was carefully soldered with a lead-tin alloy and sealed into the jar with asphalt. When König examined the objects, his mind leapt to a bold conclusion: these were not ordinary vessels but ancient galvanic cells—primitive batteries.

The very suggestion was radical. Electricity, as far as mainstream history recorded, was a discovery of the modern era, not something wielded by the ancients. König’s idea turned the jars into something more than archaeological curiosities—they became symbols of the tantalizing possibility that civilizations long past may have known secrets lost to time.

The Theory of the Ancient Battery

König’s interpretation suggested that if the jars were filled with an acidic liquid, such as vinegar or fermented grape juice, a simple electrochemical reaction would occur. The iron rod would serve as the anode, the copper as the cathode, and the liquid as the electrolyte. Together, these components could generate a small electric current.

This explanation electrified the imagination of the public and scholars alike. Suddenly, the Baghdad Battery was heralded as proof of ancient electricity. Books and documentaries eagerly adopted the theory, often embellishing it with speculation. Theories multiplied: perhaps the Mesopotamians used these jars to electroplate gold onto silver objects; maybe they were instruments of healing, used in some form of electrotherapy; or, in the most fantastical accounts, they were evidence of knowledge passed down from extraterrestrial visitors.

The Baghdad Battery thus became a bridge between hard science and cultural myth, an archaeological artifact that seemed to defy time.

Experimenting with the Past

To test König’s hypothesis, scientists and enthusiasts attempted to recreate the Baghdad Battery. In the 1970s, Dr. Arne Eggebrecht, then director of the Roemer and Pelizaeus Museum in Hildesheim, Germany, built replicas of the jar. When filled with grape juice or vinegar, his models produced between 0.5 and 1 volt of electricity. While this was a modest current, it was undeniable: the device could, in fact, function as a simple battery.

Later experiments by other researchers confirmed these findings. The Baghdad Battery could indeed generate electricity, though weak and unstable. It was enough, theoretically, to produce a tingling sensation on the skin or to power very rudimentary electroplating. This experimental evidence lent credence to König’s daring hypothesis, and for many, it seemed the case was closed: the ancients had mastered electricity.

But as with most things in history, the truth is rarely so straightforward.

The Problem with the Battery Hypothesis

While the Baghdad Battery can function as a primitive electrochemical cell under modern reconstruction, the leap to conclude that this was its original purpose is problematic. The first issue is archaeological context. The jars were not found in situ during König’s time; they had been excavated earlier, possibly during digs at Khujut Rabu near Baghdad, but the exact context was poorly documented. Without a clear record of where and how they were discovered, connecting them to a specific use or cultural practice is tenuous.

Secondly, there is no supporting evidence. If ancient Mesopotamians or Parthians (the likely creators of the jars, around 250 BCE to 250 CE) truly understood electricity, where are the other signs? Electroplated artifacts, extensive use of such technology, or written references? None have been conclusively identified. Electroplated objects once attributed to ancient Mesopotamia have since been shown to be modern fakes or misinterpretations.

Finally, the jars themselves raise doubts. The asphalt sealant and iron rod show heavy corrosion, suggesting that if a liquid had once been present, it may have been something other than an acidic electrolyte. The objects could have had a completely different function—one rooted in ritual or storage rather than science.

Alternative Explanations

Scholars have proposed less sensational but perhaps more realistic explanations for the Baghdad Battery. One suggestion is that these jars were simple storage vessels, possibly used for scrolls or sacred texts. The copper cylinder could have served as a protective container, and the asphalt sealant would have kept out moisture.

Another theory posits that the jars were used in ritual practices. The combination of metals and organic materials could have held symbolic significance, perhaps tied to religious ceremonies. In ancient cultures, the line between science and spirituality was often blurred, and what we interpret as technology might have been seen as ritual symbolism.

The jars could also have been medical devices, though not in the way König imagined. The metallic and organic components might have been used in traditional healing practices, perhaps as containers for herbal mixtures or poultices.

These alternatives remind us of an important principle in archaeology: just because an artifact can perform a modern function does not mean that was its intended use.

The Allure of the Unknown

Why, then, does the Baghdad Battery continue to captivate the world? The answer lies not only in science but in human imagination. We are drawn to mysteries, especially those that suggest lost knowledge or hidden histories. The idea that ancient civilizations might have possessed technologies rivaling or prefiguring our own taps into a deep yearning: the desire to believe that humanity’s story is richer, stranger, and more advanced than we think.

The Baghdad Battery feeds this yearning perfectly. It is small, enigmatic, and seemingly out of place. It invites us to dream of forgotten sciences, secret traditions, or even cosmic visitors who shared their wisdom with ancient peoples. In this sense, the Baghdad Battery is more than an artifact—it is a mirror reflecting our hopes, fears, and fantasies about the past.

The Science of Skepticism

Yet science demands skepticism. While imagination is a powerful tool, conclusions must rest on evidence. The Baghdad Battery teaches us an invaluable lesson: context matters. An object divorced from its archaeological setting becomes a canvas for speculation, but without context, certainty is elusive.

Archaeologists today stress the importance of careful excavation, thorough documentation, and interdisciplinary analysis. Had the Baghdad jars been excavated with modern methods, their purpose might be clearer. Instead, we are left with tantalizing fragments, half-clues that invite conjecture but resist final answers.

The Broader Context of Ancient Technology

The Baghdad Battery, regardless of its true purpose, reminds us of something essential: ancient civilizations were not primitive. The Mesopotamians, Egyptians, Greeks, and others developed astonishing technologies—water clocks, irrigation systems, astronomical observations, and medical treatments—that laid the foundation for modern science.

The Parthians, the likely creators of the battery jars, were skilled in metallurgy, engineering, and craftsmanship. They built impressive cities, traded across continents, and left behind cultural legacies that shaped the world. Even if they did not harness electricity, their ingenuity was profound and deserves recognition without sensationalism.

Between Fact and Myth

In the end, the Baghdad Battery may never reveal its full story. Perhaps it was a humble storage vessel, a ritual object, or an accidental proto-battery. Perhaps it was all of these at once. Its ambiguity ensures its immortality, for mysteries endure where facts fade.

What is certain is that the Baghdad Battery has transcended its physical form. It has become a symbol of the intersection between science and imagination, a reminder that artifacts are not only relics of the past but catalysts for wonder. Its true function may lie not in electroplating or rituals but in sparking curiosity—igniting our desire to question, to test, and to dream.

The Legacy of a Clay Jar

Today, the Baghdad Battery resides in the Iraq Museum, though it has faced threats of looting and destruction during times of conflict. Its survival is itself a testament to resilience—the resilience of objects that carry stories through centuries of upheaval.

For scientists, it remains a puzzle worth examining, a case study in the importance of evidence and restraint. For storytellers, it is a treasure trove of possibility, a doorway into alternative histories and science fiction. For the rest of us, it is a reminder that even the smallest objects can change how we see the world.

Conclusion: A Spark in the Darkness

So, what is the true function of the Baghdad Battery? Scientifically, we may never know with certainty. It might have been a container, a ritual item, or an accidental electrochemical device. But beyond its material purpose, its function is clear: it sparks curiosity, challenges assumptions, and bridges the gap between the known and the unknown.

In that sense, the Baghdad Battery is less about volts and currents and more about the enduring power of wonder. It whispers across millennia that the past is not a closed book but a living dialogue, one where every discovery is a question as much as an answer.

When we gaze upon this humble clay jar, we are not only looking at an artifact. We are staring into a mirror, seeing our own fascination with mystery reflected back at us. And perhaps, just perhaps, that is its truest function of all.