For decades, the story of early humans in East Asia was told in muted tones. The region was often portrayed as a technological backwater, a place where ancient hominins clung to simple stone tools while innovation flourished elsewhere. That story began to unravel at a site called Xigou, tucked within the Danjiangkou Reservoir Region of central China, where layers of earth quietly preserved a very different past.

When archaeologists began carefully excavating the site, they did not expect to challenge a narrative that had dominated scientific thinking for generations. Yet as stone after stone emerged from the ground, it became clear that Xigou was not merely another ancient campsite. It was evidence of a forgotten chapter in human ingenuity, one that stretched back between 160,000 and 72,000 years ago and demanded to be heard.

When Old Assumptions Start to Crack

The excavation, led by the Chinese Academy of Sciences in collaboration with an international research team including Griffith University, revealed something startling. The hominins who lived in this region were not passive inheritors of simple traditions. They were active problem-solvers, experimenting with technology in ways that had long been thought exclusive to Africa and western Europe.

For years, researchers argued that while early humans in those regions pushed technological boundaries, East Asian hominins followed conservative stone-tool traditions with little change over time. Dr. Shixia Yang of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology summarized this long-held view bluntly, noting that innovation was assumed to be unevenly distributed across the ancient world.

But the tools uncovered at Xigou refused to fit that mold. Their shapes, sizes, and production methods spoke of deliberate planning and technical skill. They suggested a population that understood stone not just as something to break, but as something to shape with intention.

Stones That Tell a Smarter Story

Detailed analysis of the artifacts revealed sophisticated stone toolmaking methods. Hominins at Xigou produced small flakes and tools designed for a wide range of tasks, indicating a flexible approach to daily life. These were not crude, one-purpose objects. They were tools born of experimentation and refinement, shaped to meet changing needs.

Professor Michael Petraglia, Director of Griffith University’s Australian Research Center for Human Evolution, emphasized how these findings disrupt the old narrative. The idea that early humans in China remained technologically static no longer holds up when faced with the evidence emerging from this site.

Each flake and retouched edge hinted at decision-making processes that went beyond basic survival. The tools suggested foresight, adaptation, and an understanding of how subtle changes in form could dramatically improve function.

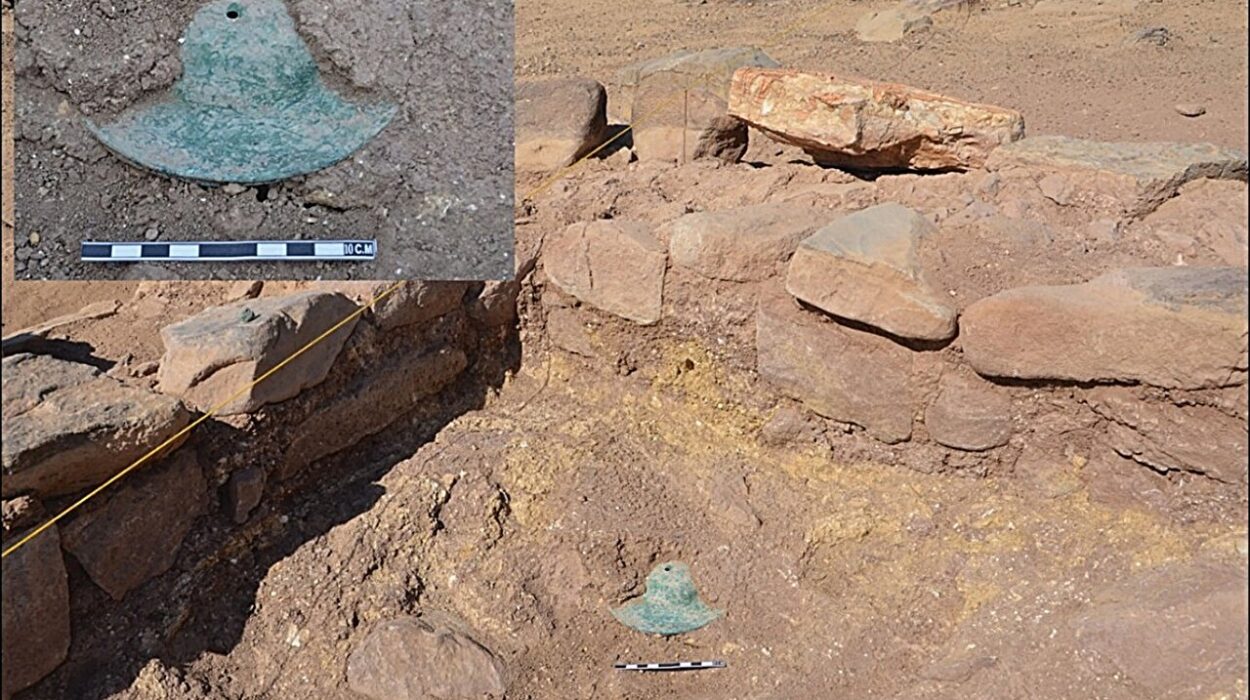

The Shock of the Handle

Among all the discoveries at Xigou, one stood out with particular force. Archaeologists identified hafted stone tools, marking the earliest-known evidence of composite tools in East Asia. These tools combined stone components with handles or shafts, transforming sharp fragments into more efficient and controllable instruments.

Hafting is not a simple act. It requires multiple steps, careful planning, and an understanding of how different materials work together. A stone blade must be shaped to fit a handle. The handle must be prepared to hold it. The final product reflects a mental blueprint that exists long before the tool itself.

Dr. Jian-Ping Yue, the study’s lead author, described these tools as clear evidence of behavioral flexibility and ingenuity. Their presence at Xigou suggests that hominins here were not merely reacting to their environment. They were anticipating challenges and engineering solutions.

A Crowded Landscape of Minds

The timeframe represented at Xigou overlaps with a period of remarkable hominin diversity in China. During these tens of thousands of years, multiple large-brained hominins inhabited the region. Fossils from sites such as Xujiayao and Lingjing, sometimes associated with Homo juluensis, point to populations with substantial cognitive capacity. Alongside them may have been Homo longi and possibly even Homo sapiens.

Xigou’s stone tools provide a technological mirror to this biological complexity. While the site does not assign specific tools to specific species, the behavioral sophistication embedded in the artifacts aligns with what might be expected from large-brained hominins navigating challenging and changing circumstances.

Rather than a single, static population, the archaeological layers suggest a dynamic human presence, one capable of learning, adapting, and innovating over time.

Ninety Thousand Years of Adaptation

One of Xigou’s most remarkable features is the sheer length of time it represents. The site’s deposits span roughly 90,000 years, offering a rare glimpse into long-term technological continuity and change. Across this vast stretch of time, hominins returned to the area again and again, leaving behind tools that chart an evolving relationship with their surroundings.

Professor Petraglia noted that the technological strategies evident in the tools likely played a crucial role in helping populations adapt to fluctuating environments. As conditions shifted, the ability to modify tools, experiment with new techniques, and refine existing methods would have been essential.

This long view reveals innovation not as a sudden spark, but as a steady process of adjustment and improvement, carried forward across generations.

A Richer Toolbox Than Expected

Beyond hafted tools, the Xigou assemblage includes evidence of prepared-core methods, innovative retouched tools, and even large cutting tools. Together, they point to a technological landscape far more complex than previously recognized in early China.

Dr. Yang emphasized that these discoveries are part of a growing body of evidence showing that early technologies in the region were diverse and inventive. Xigou is not an isolated anomaly. It is a powerful data point in a broader reevaluation of East Asia’s role in human technological evolution.

The stones from this site show that creativity was not confined to one continent. It emerged wherever humans, or human relatives, were challenged to survive.

Why Xigou Changes the Human Story

The importance of the Xigou discoveries goes far beyond a single site. They reshape how scientists understand human evolution in East Asia, challenging the idea that innovation followed a simple, one-way path from west to east. Instead, the evidence suggests parallel developments, with early populations in China demonstrating cognitive and technical abilities comparable to those seen in Africa and Europe.

This matters because it changes the questions researchers ask. Rather than wondering why East Asia lagged behind, scientists can now explore how different populations solved similar problems in their own ways. It opens the door to a more balanced and inclusive view of our deep past.

Xigou reminds us that history is often shaped as much by assumptions as by evidence. When those assumptions are stripped away, the past can look startlingly new. In the quiet stones of central China, early hominins left behind a message that waited thousands of years to be understood. It says that ingenuity was never rare, and that the roots of human creativity run deeper and wider than we once believed.

Study Details

Shi-Xia Yang, Technological innovations and hafted technology in central China ~160,000–72,000 years ago, Nature Communications (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-67601-y. www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-67601-y