For as long as humans have looked up, the stars have invited imagination. Somewhere in that darkness, astronomers wonder, might there be civilizations so advanced that a single planet could no longer satisfy their energy needs. The question is not whether we have seen such beings, but whether the laws of physics would even allow their grandest ideas to exist.

A new theoretical study offers a careful, mathematical yes.

In work published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, physicist Colin McInnes of the University of Glasgow explores whether enormous, star-orbiting structures designed to harvest stellar energy could remain stable without constant correction. His calculations suggest that, under the right conditions, some of the most ambitious megastructures ever imagined could quietly endure, balanced by gravity and light alone.

Dreams of Power Beyond a Planet

The idea behind these structures is simple and breathtaking at the same time. A star pours out staggering amounts of energy every second. Compared to that flood, the energy available on a single planet is only a thin trickle. If a civilization could capture even a fraction of its star’s output, it would gain resources beyond anything we can currently conceive.

Astronomers have long speculated that such energy could support projects on a scale that sounds like science fiction: reshaping entire worlds, sustaining populations across generations in space, or embarking on journeys between stars that take centuries to complete.

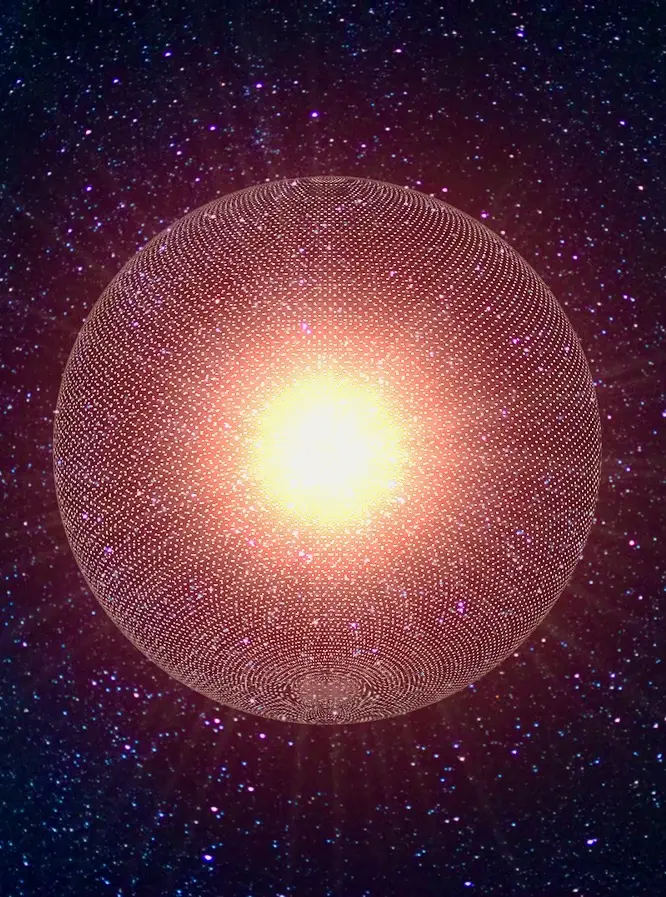

Out of these imaginings emerged concepts that are now staples of speculative astrophysics. Among them are stellar engines, colossal reflective disks that interact with a star’s light, and Dyson bubbles, swarms of smaller reflectors arranged around a star to intercept its radiation. Both aim to do the same thing: tap into the star’s immense power. Yet both face a nagging challenge that has lingered for decades.

The Fragile Problem of Staying Put

On paper, harvesting stellar energy sounds plausible. In space, however, even small imbalances can become catastrophic over time. Gravity pulls inward. Starlight pushes outward. If a structure drifts too close, it risks falling into the star. If it drifts too far, it may be flung away forever.

This long-term stability problem has been a stumbling block for serious discussion. Could such gigantic constructions survive for thousands or millions of years without constant intervention?

McInnes approached this question not as an engineer but as a mathematician of motion. “The idea of ultra-large artificial structures, such as stellar engines and Dyson bubbles around stars, has been discussed in SETI studies for some time,” he explains. His interest lies in understanding their dynamics, and whether they could be made passively stable, able to maintain their configuration without continual active control.

To do this, he built simplified models that treat these megastructures as extended objects rather than idealized points. This allowed him to calculate how gravitational forces and radiation pressure from starlight would act across their full shapes.

The results were surprisingly encouraging.

When a Star Becomes a Vehicle

Stellar engines are among the most audacious ideas ever proposed. In theory, a massive reflective disk could be positioned near a star so that the momentum of reflected light produces thrust. Over immense timescales, that thrust could gently accelerate the star itself, along with all its orbiting planets. An entire star system would become a slow but purposeful spacecraft.

But such a disk must remain aligned with exquisite precision. McInnes’s models reveal that the key lies not in how big the disk is, but in how its mass is arranged.

If the reflector’s mass is spread evenly, like a flat dinner plate, the structure is always unstable. Any slight disturbance grows, and the disk cannot naturally correct itself. It would require constant, active adjustments to avoid disaster.

Change the design, however, and the physics change with it. When most of the mass is concentrated in an outer ring, giving the structure a form more like a tambourine, the equations tell a different story. In this configuration, the stellar engine can become gravitationally stable. Small deviations do not spiral out of control. Instead, the structure gently settles back into place.

In principle, such a design could quietly maintain itself, balanced between the inward pull of gravity and the outward push of light.

A Swarm That Finds Its Balance

Dyson bubbles take a different approach. Rather than one enormous object, they consist of vast numbers of low-mass reflectors arranged in a cloud around the star. Each element interacts with starlight and gravity, and together they intercept a substantial portion of the star’s energy.

The challenge here is collective behavior. Too sparse a swarm, and the reflectors drift unpredictably. Too massive, and the cloud’s own gravity overwhelms the delicate balance needed to stay aloft.

McInnes examined a scenario where the swarm is dense enough to significantly dim the star’s light, yet light enough that the star’s gravity still dominates. In this sweet spot, something remarkable happens. The reflectors can naturally rearrange themselves into stable configurations.

Rather than crashing inward or escaping outward, each element of the cloud oscillates gently, responding to the competing forces acting upon it. “This passive stability is arguably a more realistic choice than active control for such long-lived structures,” McInnes notes. The system does not fight physics. It flows with it.

The Subtle Art of Letting Physics Do the Work

What unites these findings is not a claim that such structures exist, but a demonstration that they are not forbidden. With careful design, the laws of physics allow stellar engines and Dyson bubbles to maintain themselves through natural forces alone.

This matters because active control over cosmic timescales is an enormous burden. Systems that require constant adjustment are vulnerable to failure. Passive stability, by contrast, offers resilience. It allows structures to endure quietly, correcting small disturbances through their own dynamics.

By showing how mass distribution and swarm density influence stability, McInnes’s models move these ideas from pure fantasy toward disciplined theoretical possibility.

Why This Research Matters

At first glance, this work may seem far removed from everyday science. It speaks of civilizations we have never met and structures we have never seen. Yet its importance lies in sharpening our understanding of what is physically possible.

By clarifying how advanced energy-harvesting systems could be engineered in theory, the research helps astronomers refine what they might look for when studying distant stars. If such megastructures exist, they may leave subtle signatures in the light we observe. Knowing which configurations are stable helps guide those searches toward realistic targets.

More broadly, this study reminds us that imagination and mathematics are partners in discovery. Speculation becomes meaningful when it is disciplined by physical law. McInnes’s work does not claim that stellar engines or Dyson bubbles are out there. It shows something quieter and perhaps more profound: that the universe would allow them.

In doing so, it invites us to keep asking questions that stretch beyond our current reach, while grounding those questions in the steady logic of physics. The stars may still be silent, but studies like this help us listen with clearer expectations—and deeper wonder.

Study Details

Colin R McInnes, Stellar engines and Dyson bubbles can be stable, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (2026). DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stag100