For most of human history, the universe seemed built only from what our eyes could catch. Stars burned, galaxies spun, planets gathered dust and hope. Yet beneath all of it, an invisible presence has been quietly shaping the cosmos. Now, scientists have drawn the sharpest map ever made of that hidden force, revealing how it threads through space and sculpts everything we know.

Using new observations from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, an international team of astronomers has created the highest-resolution map of dark matter ever achieved. This is not just a technical milestone. It is a glimpse into the unseen architecture that helped pull ordinary matter together, allowing stars, galaxies, and eventually planets like Earth to form.

The research, published in Nature Astronomy, brings together scientists from Durham University, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and EPFL in Switzerland. Together, they have turned Webb’s extraordinary vision toward a simple but profound question: how did the invisible shape the visible?

When the Universe Was Thin and Quiet

At the beginning, the universe was sparse. Matter—both ordinary and dark—was spread thin, drifting through an expanding sea of space. Nothing yet resembled the structured cosmos we inhabit today.

Scientists believe that dark matter clumped together first, long before stars began to shine. While ordinary matter floated freely, dark matter gathered into denser regions. These invisible concentrations exerted gravity, quietly tugging normal matter toward them. Over time, gas and dust fell into these gravitational wells, growing denser, warmer, and more complex.

This process created the first regions where galaxies and stars could begin to form. In this way, dark matter did not merely accompany cosmic evolution. It set the stage for it.

By encouraging galaxies and stars to emerge earlier than they otherwise might have, dark matter also helped create the conditions needed for planets. Without this invisible scaffolding, scientists say, the elements required for life may never have assembled in galaxies like the Milky Way.

The Invisible Architect Revealed

Dr. Gavin Leroy of Durham University describes the new map as a turning point in our understanding. By revealing dark matter with unprecedented precision, he explains, scientists can finally see how an invisible component of the universe structured visible matter all the way to the emergence of life itself.

The map confirms earlier research but adds striking new detail. Where previous studies suggested a relationship between dark matter and normal matter, this one shows just how tightly they are entwined. The alignment is so close that it cannot be dismissed as chance.

Everywhere astronomers find ordinary matter, they also find dark matter. Galaxies do not sit alone in space; they are wrapped in vast, swirling clouds of unseen mass. These clouds provide the gravity that holds galaxies together and gives them their shape.

Professor Richard Massey, also of Durham University, offers a striking perspective. Billions of dark matter particles pass through your body every second, he says, unnoticed and harmless. They do not interact with light. They do not bump into atoms. They simply pass through, like ghosts.

Yet collectively, they matter enormously. The dark matter surrounding the Milky Way has enough gravity to hold the entire galaxy together. Without it, the galaxy would spin itself apart.

Seeing Gravity Instead of Light

Dark matter presents a frustrating challenge. It does not emit, reflect, absorb, or block light. Telescopes cannot photograph it directly. Instead, astronomers must look for its influence.

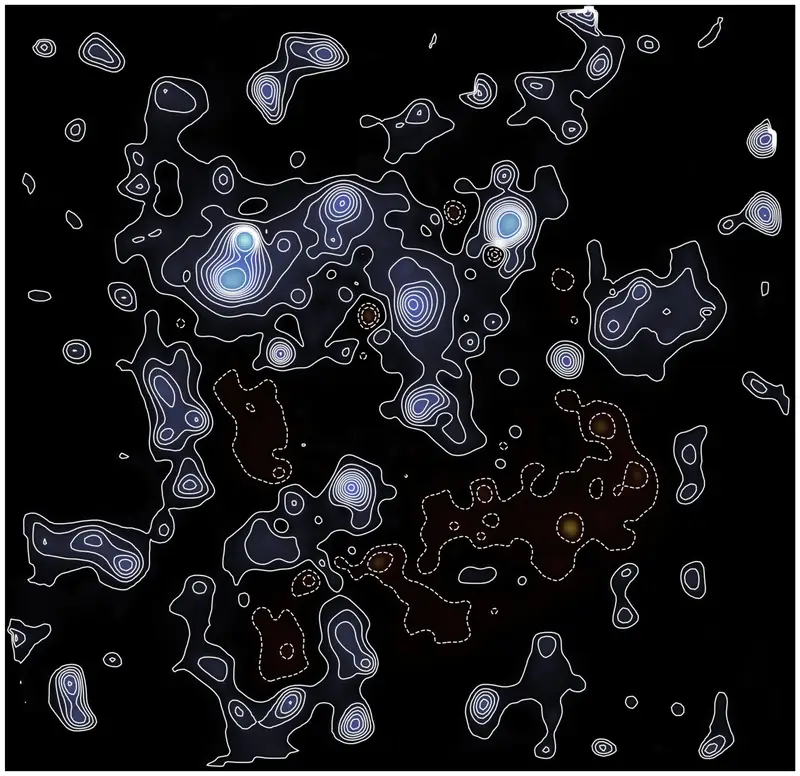

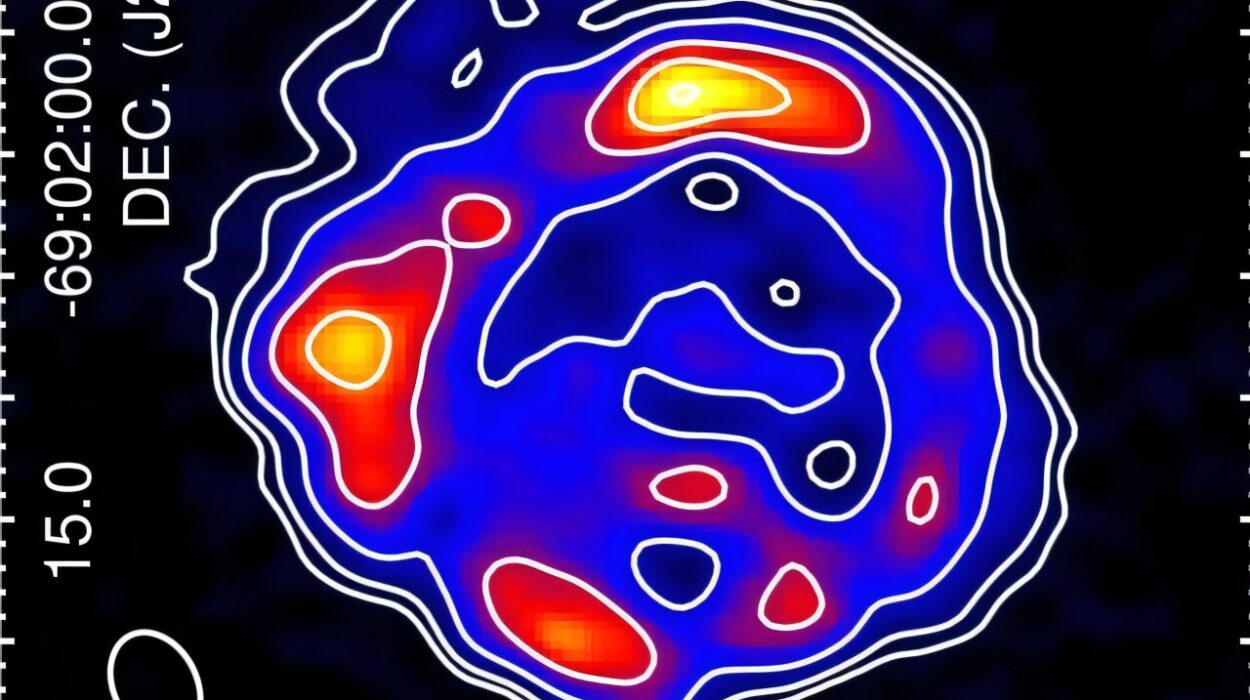

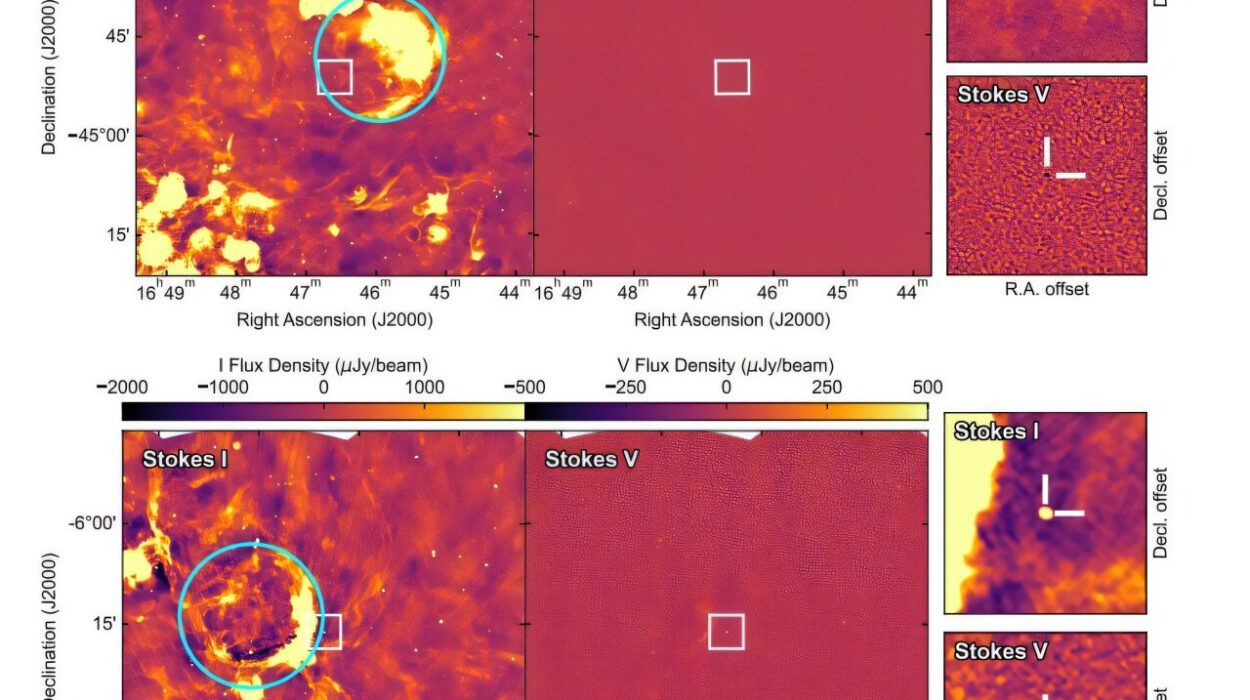

The new map does exactly that. Rather than trying to see dark matter itself, the team observed how its mass curves space, bending the path of light traveling from distant galaxies to Earth. The effect is subtle, like looking through a warped windowpane, but with Webb’s sensitivity, those distortions become measurable.

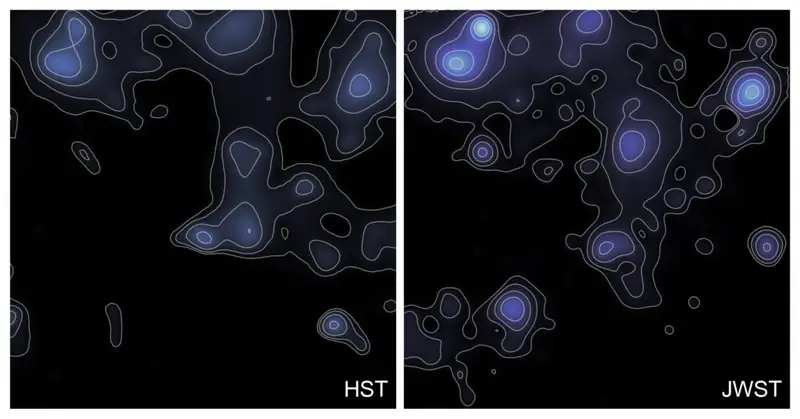

By carefully analyzing how the shapes of distant galaxies appear stretched and skewed, scientists can trace the gravitational fingerprints of dark matter lying between those galaxies and us. From these distortions, a detailed map of dark matter emerges.

This approach reveals not only where dark matter is, but how densely it is packed and how it relates to the distribution of normal matter across cosmic time.

A Small Patch of Sky, Crowded with Secrets

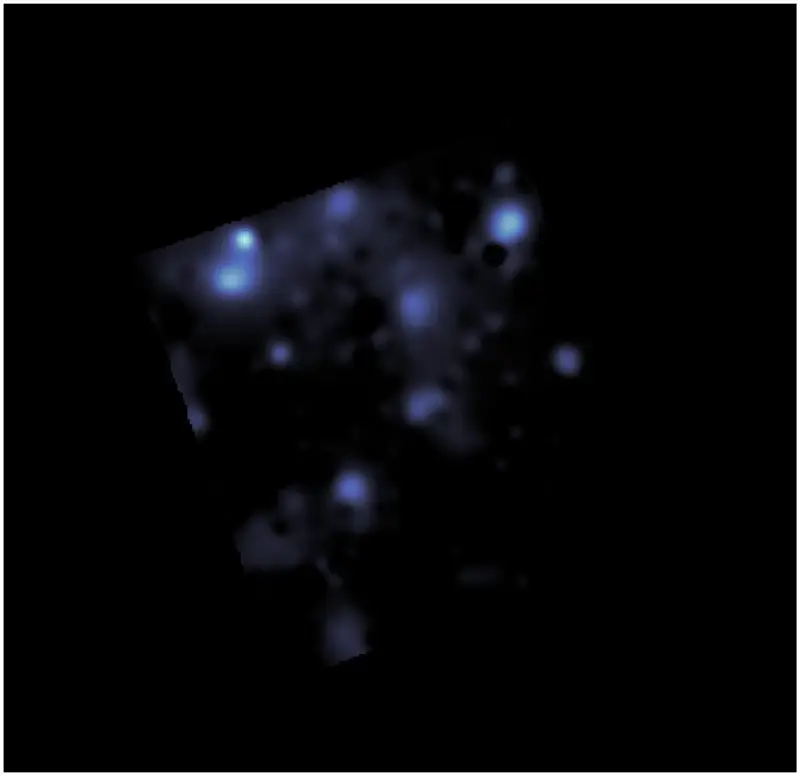

The map focuses on a region of sky in the constellation Sextans, covering an area about 2.5 times larger than the full moon. Though modest in size, this patch of sky is rich with information.

Webb observed this region for about 255 hours, peering deep into space and time. In that area alone, it identified nearly 800,000 galaxies, many of which had never been detected before.

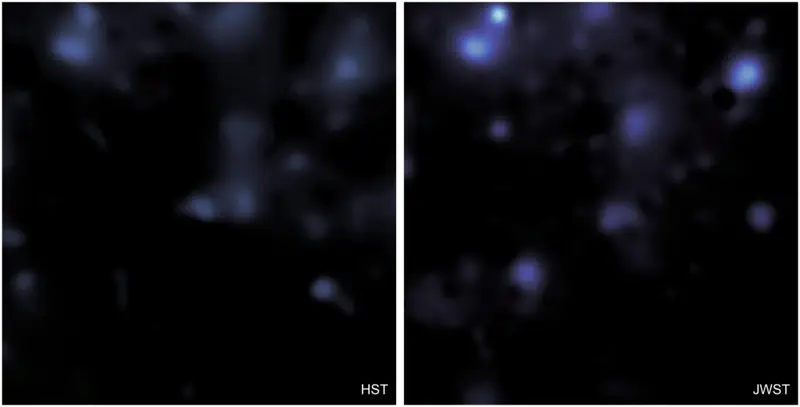

Compared to earlier efforts, the improvement is dramatic. The new map contains ten times more galaxies than ground-based observatory maps of the same region and twice as many as those made by the Hubble Space Telescope. With more galaxies come more data points, and with more data points comes sharper clarity.

The result is a view that reveals new clumps of dark matter and offers a far more detailed look at regions previously seen only in blurrier outlines.

From Blurry Shadows to Sharp Structure

Dr. Diana Scognamiglio of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory describes the leap forward with a simple image. Previously, she says, scientists were looking at a blurry picture of dark matter. Now, thanks to Webb’s resolution, they can see the invisible scaffolding of the universe in stunning detail.

This is the largest dark matter map ever made using Webb, and it is twice as sharp as any dark matter map produced by other observatories. Fine structures that once blended together now stand out clearly, offering clues about how dark matter behaves and how it has evolved.

To refine their measurements further, the team used Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument, known as MIRI, to determine the distances to many of the galaxies in the map. These distances are crucial, allowing astronomers to place dark matter structures accurately in three-dimensional space.

Durham University’s Center for Extragalactic Astronomy played a role in the development of MIRI, which was designed and managed through launch by JPL. The instrument’s ability to detect wavelengths that pass through cosmic dust clouds made it especially effective at uncovering galaxies that might otherwise remain hidden.

A Reference Point for the Future Universe

This map is not an endpoint. It is a foundation.

The team plans to expand their efforts using the European Space Agency’s Euclid telescope and NASA’s upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope. With these missions, they aim to map dark matter across the entire universe, learning more about its fundamental properties and how it may have changed over cosmic history.

Yet the small region of sky studied here will remain special. It will serve as the reference standard against which future dark matter maps are calibrated and compared. In essence, it becomes the benchmark for how clearly we can see the invisible.

Why This Research Matters

This work matters because it answers a question deeper than where galaxies are. It tells us why they exist at all.

Dark matter does not glow or sparkle, but without it, the universe would be a very different place. Galaxies like the Milky Way might never have formed. The elements needed for planets might never have gathered. The conditions that allowed life to emerge may never have arisen.

By mapping dark matter with unprecedented precision, scientists are uncovering the hidden framework that shaped everything we see and everything we are. This research transforms dark matter from an abstract idea into a tangible structure, one that quietly organized the universe long before the first stars ignited.

In revealing the invisible architect of the cosmos, this map reminds us that the most important forces in the universe are not always the ones we can see—but they are the ones that made seeing possible at all.

Study Details

Diana Scognamiglio, An ultra-high-resolution map of (dark) matter, Nature Astronomy (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41550-025-02763-9. www.nature.com/articles/s41550-025-02763-9