For decades, astronomers have sifted through the faint fingerprints of stars, searching for the rare ones that carry stories from the universe’s earliest chapters. Most stars are chemically rich, born from generations of cosmic recycling. But a small, elusive group stands apart, poor in heavy elements yet strangely rich in carbon. These stars are so uncommon that each new discovery feels like finding a surviving page from a nearly lost book.

Now, for the first time, that kind of page has been found in a neighboring galaxy. Using the Baryons Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey (BOSS) spectrograph, astronomers have identified five carbon-enhanced metal-poor stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a dwarf satellite galaxy of the Milky Way. The finding, reported in a paper released on January 15 on the arXiv pre-print server, quietly changes what scientists thought they knew about where these stars could exist.

Stars That Remember the Early Universe

To understand why this matters, it helps to know what makes these stars so special. Astronomers describe a star as “metal-poor” when it contains very little iron compared to the Sun. Specifically, stars with iron abundances [Fe/H] below −2.0 fall into this rare category. Only a few thousand such stars have ever been identified.

These stars are valuable because they act like chemical fossils. Their compositions preserve clues about the universe at a time when heavy elements were scarce. Each one can tell astronomers something about how galaxies grew and evolved chemically over time.

Within this already rare group, many stars show something even more unusual. They are enriched with carbon far beyond what their iron content would suggest. These are known as carbon-enhanced metal-poor stars, or CEMP stars. In the Milky Way, astronomers have found many of them. But when they looked beyond our galaxy, something strange happened.

The Galaxy Where None Were Found

Despite years of searching, astronomers had never identified a confirmed CEMP star in the Large Magellanic Cloud, often abbreviated as the LMC. This was puzzling. The LMC is the Milky Way’s largest dwarf companion galaxy, close enough to study in detail and massive enough to host ancient stellar populations.

Even more confusing was the broader pattern. While the Milky Way contained many CEMP stars, dwarf spheroidal galaxies appeared to show an observational deficit. The stars either weren’t there, or they were hiding too well to be detected.

This absence raised uncomfortable questions. Did the chemical evolution of smaller galaxies somehow prevent the formation of CEMP stars? Or were astronomers simply missing them?

A Targeted Search Through a Stellar Crowd

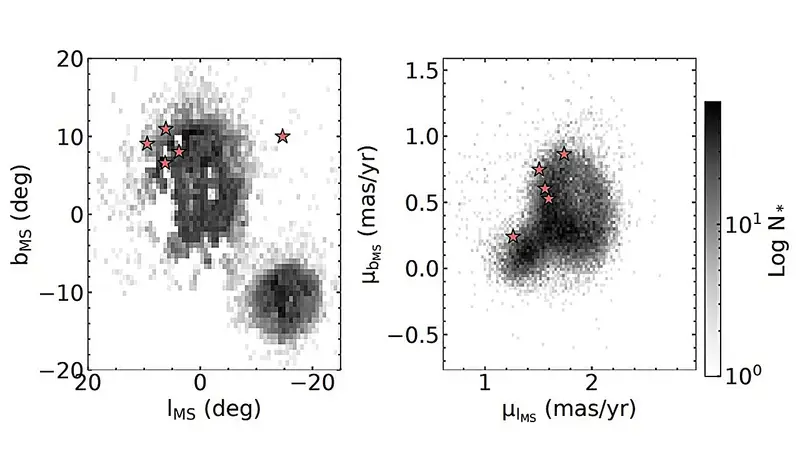

To find answers, a team of astronomers led by Madeline Lucey of the University of Pennsylvania turned to a powerful dataset. They analyzed observations from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, focusing on data collected through the SDSS-V Magellanic Genesis program.

Their approach was deliberate. Instead of searching blindly, they examined stars already flagged as potential CEMP candidates based on their spectral signatures. In total, the team analyzed 381 stars from the SDSS-V DR20 Magellanic Genesis catalog.

Starlight, when split into a spectrum, carries information about a star’s chemical makeup. Subtle absorption features can reveal how much iron, carbon, and other elements are present. Among the hundreds of candidates, Lucey’s team looked for the strongest signals: the lowest metallicities combined with the highest carbon enhancements.

Five Stars That Stood Out

From the full sample, five stars clearly rose above the rest. These stars showed both extremely low iron content and strikingly high carbon-to-iron ratios. They were designated SDSS 92278782, SDSS 96041179, SDSS 98320880, SDSS 98332219, and SDSS 98357416.

Their chemical fingerprints were remarkable. The stars had metallicities ranging from −3.21 to −2.09, placing them among the most metal-poor objects known. At the same time, their carbon-to-iron abundance ratios [C/Fe] ranged from 1.23 to 2.41, a clear hallmark of carbon enhancement.

Temperature measurements added another piece to the puzzle. All five stars fell within a narrow range of 4,600 to 4,850 Kelvin, suggesting they share similar physical characteristics despite their rarity.

Taken together, these properties strongly indicate that the stars belong to the CEMP category. And crucially, they reside in the LMC.

A Discovery With Cautious Language

Even with such compelling evidence, the researchers were careful in how they framed their conclusions. While the stars are most likely CEMP stars, the team emphasized that classifications developed within the Milky Way might not translate perfectly to other galaxies.

Different galaxies experience different histories of star formation and chemical enrichment. Because of this, it remains uncertain whether the same definitions should apply beyond our home galaxy without modification.

To resolve this uncertainty, the authors noted that higher-resolution spectra are needed. These would allow astronomers to measure neutron-capture element abundances, which are essential for confirming the precise nature of these stars. Until then, the classification remains highly probable, but not final.

Opening a Door That Was Thought Closed

Despite the remaining questions, the significance of the discovery is clear. For the first time, astronomers have strong evidence that carbon-enhanced metal-poor stars do exist in the Large Magellanic Cloud.

This finding suggests that the apparent absence of such stars in dwarf galaxies may not reflect a true cosmic difference, but rather the limits of previous observations. The stars were there all along, faint and chemically subtle, waiting for the right tools and the right analysis to reveal them.

What Comes Next in the Search

The team sees this discovery not as an endpoint, but as a beginning. In their concluding remarks, they describe the five stars as a crucial step toward a deeper understanding of the LMC’s most metal-poor stellar populations.

Future work will expand the search. The researchers plan to homogeneously analyze all of the BOSS spectra from both the Large Magellanic Cloud and the Small Magellanic Cloud collected through SDSS-V. Their goal is to measure how often CEMP stars occur in these galaxies and to compare those rates directly with the Milky Way.

Such comparisons could reveal whether different galaxies truly follow different chemical paths, or whether they share more common ground than previously believed.

Why These Five Stars Matter

At first glance, five stars might seem like a small result in a universe filled with billions. But these stars carry outsized importance. Metal-poor stars help astronomers reconstruct the chemical evolution of galaxies, and carbon-enhanced ones offer especially rich clues about early stellar processes.

Finding them in the Large Magellanic Cloud challenges assumptions about where such stars can form and survive. It suggests that even in galaxies with different masses and histories, the universe may follow familiar chemical patterns.

More broadly, the discovery shows how careful observation and persistence can overturn long-held gaps in knowledge. By uncovering these five faint, ancient stars, astronomers have opened a new window into the chemical story of a neighboring galaxy—and taken one step closer to understanding how the earliest generations of stars shaped the cosmos we see today.

Study Details

Madeline Lucey et al, Discovery of the First Five Carbon-Enhanced Metal-Poor Stars in the LMC, arXiv (2026). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2601.10514