“A plague is upon us” may sound like a line from legend, but in ancient Jordan it was a lived reality. In the city of Jerash, life once unfolded in bustling streets shaped by trade, movement, and everyday routines. Then something invisible arrived. People began to die in numbers that overwhelmed memory and ritual. Centuries later, their story is being told again—not through chronicles or rumor, but through bones, soil, and the careful work of scientists who wanted to understand what pandemic death truly looked like inside a real city.

An interdisciplinary team from the University of South Florida, led by public health researcher Rays H. Y. Jiang, has completed the third paper in a series exploring the Plague of Justinian, the first-known outbreak of bubonic plague in the Mediterranean world. Their study, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, does something rare. It steps away from the pathogen alone and turns toward the people whose lives were cut short by it.

Rather than asking only what caused the plague, the researchers asked who suffered, how they lived, and how a city responded when death arrived faster than tradition could manage.

A Layer of Pottery, Then Silence

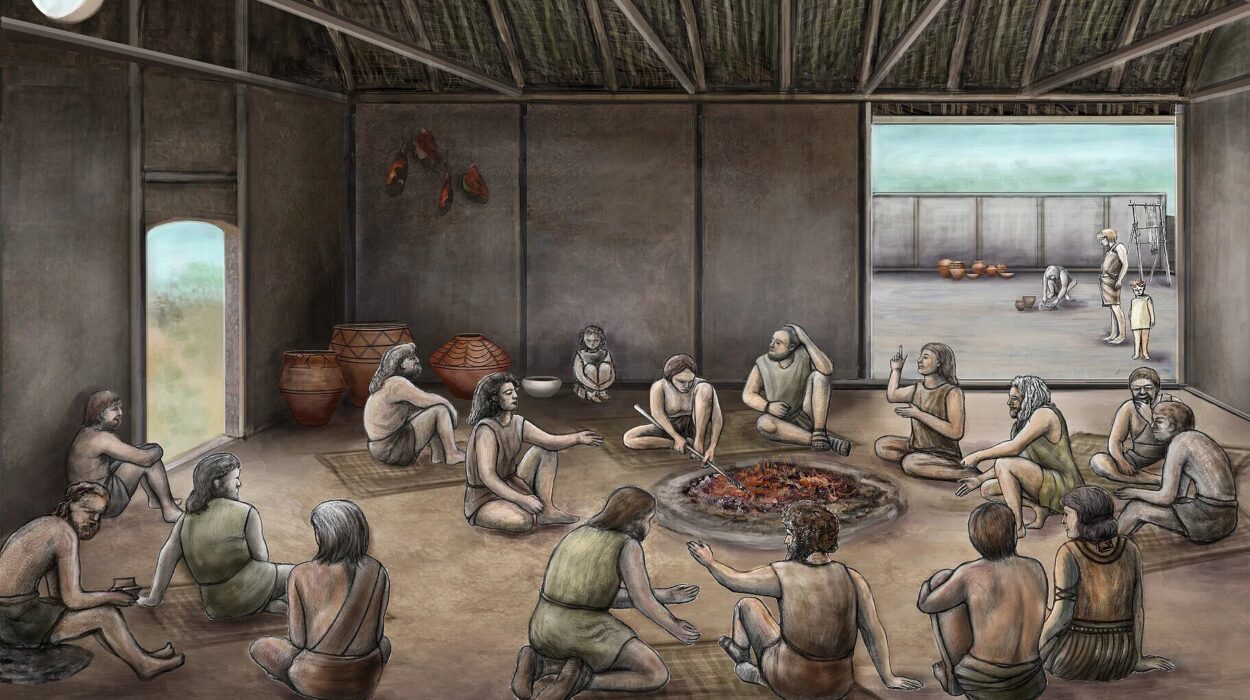

In Jerash, the evidence of catastrophe lies in an unexpected place. Hundreds of bodies were found rapidly deposited atop layers of pottery debris in what had once been an active civic space. This was not a cemetery shaped over generations. It was an emergency response, a single mortuary event that unfolded within days.

The team describes this as fundamentally different from normal burial practices. Civic cemeteries grow slowly, each grave marking a familiar loss. At Jerash, the pace was relentless. The dead were gathered and placed together, transforming an abandoned space into a mass grave born of necessity rather than ritual.

This moment, frozen in soil, became the focal point of the research. It offered something historians and archaeologists had long searched for: direct, physical evidence of large-scale mortality during the Plague of Justinian.

While historical texts describe widespread devastation across the Byzantine Empire, many proposed plague mass burials have remained speculative. Jerash changes that. It is the first site where a plague mass grave has been confirmed both archaeologically and genetically.

Turning a Genetic Signal Into a Human Story

Earlier studies by the same team had already identified Yersinia pestis, the bacterium responsible for deadly forms of plague. That work established the presence of the pathogen. But Jiang and his colleagues wanted more than confirmation of disease.

“We wanted to move beyond identifying the pathogen,” Jiang explained, “and focus on the people it affected, who they were, how they lived and what pandemic death looked like inside a real city.”

To do that, the team brought together expertise from genomics, anthropology, molecular medicine, and history, along with collaborators from Sydney University and a DNA laboratory at Florida Atlantic University. By linking biological evidence from the bodies to the archaeological context, they could see how disease intersected with daily life.

The Jerash site allowed them to transform a genetic signal into a lived human narrative. The plague was no longer an abstract force moving across maps. It became a crisis experienced by neighbors, families, and communities suddenly bound together in death.

The Puzzle of Movement Written in Bone

One of the most surprising insights from the Jerash mass grave is what it reveals about movement in the ancient world. For years, historians and geneticists have faced a contradiction. On one hand, evidence shows people moved and mixed across regions through trade, migration, and empire. On the other, most burials suggest individuals grew up where they were eventually laid to rest.

Jerash shows how both can be true.

The individuals buried in the mass grave appear to have been part of a mobile population embedded within the broader urban community of ancient Jordan. Under normal circumstances, these mobile groups were dispersed across the landscape and diluted within everyday life. Their movement happened gradually, often over generations, making it difficult to detect in traditional cemeteries.

Crisis changed that pattern.

When the plague struck, these otherwise scattered individuals were suddenly concentrated in one place. The mass grave captured long-term patterns of movement in a single, devastating moment. What daily life concealed, pandemic death revealed.

The finding reframes how scholars understand vulnerability in ancient cities. Mobility did not disappear simply because communities appeared local. Instead, it was woven quietly into urban life, becoming visible only when disaster forced people together.

Seeing a Pandemic as It Was Lived

Historical sources often speak of pandemics in sweeping terms—cities emptied, empires weakened, millions lost. But such descriptions can flatten human experience into numbers and timelines. The Jerash study resists that flattening.

By examining the physical remains within their social and environmental setting, the researchers show how disease affected real people. These were not anonymous victims of an inevitable catastrophe. They were members of a city navigating fear, urgency, and impossible decisions about the dead.

The single mortuary event at Jerash reflects a civic response under pressure. It shows how normal practices gave way when overwhelmed by scale and speed. The city adapted, not through careful planning, but through necessity.

As Jiang noted, understanding pandemics this way allows us to see them not just as outbreaks recorded in text, but as lived human health events.

Echoes That Reach the Present

Although the study is rooted in the period between 541 and 750 CE, its implications extend far beyond antiquity. The researchers emphasize that pandemics are not only biological phenomena. They are also deeply social events.

The same forces that shaped the plague’s impact in Jerash—dense urban living, movement of people, and environmental context—remain central to how diseases affect societies. Pandemics expose patterns of vulnerability. They show who is most at risk and why, often revealing inequalities and connections that daily life keeps hidden.

This research helps reshape how pandemics are understood across time. It suggests that to fully grasp their consequences, we must look beyond pathogens and ask how cities, communities, and individuals experience crisis.

Why This Discovery Matters Now

The mass grave at Jerash does more than confirm the presence of the Plague of Justinian. It humanizes one of history’s earliest pandemics and grounds it in the lived reality of a single city. By doing so, it bridges the gap between genetic data, archaeological evidence, and human experience.

This matters because pandemics do not belong only to the past. They are recurring events that challenge how societies care for the vulnerable, manage movement, and respond under pressure. By understanding how an ancient city confronted sudden, overwhelming loss, we gain insight into the enduring relationship between disease and social life.

Jerash reminds us that behind every pathogen is a community, and behind every statistic are people whose lives were shaped—and ended—by crisis. Studying those moments with care and humanity helps ensure that pandemics are remembered not just for the damage they cause, but for what they reveal about who we are when everything familiar falls away.

Study Details

Karen Hendrix et al, Bioarchaeological signatures during the Plague of Justinian (541–750 CE) in Jerash (ancient Gerasa), Jordan, Journal of Archaeological Science (2026). DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2026.106473