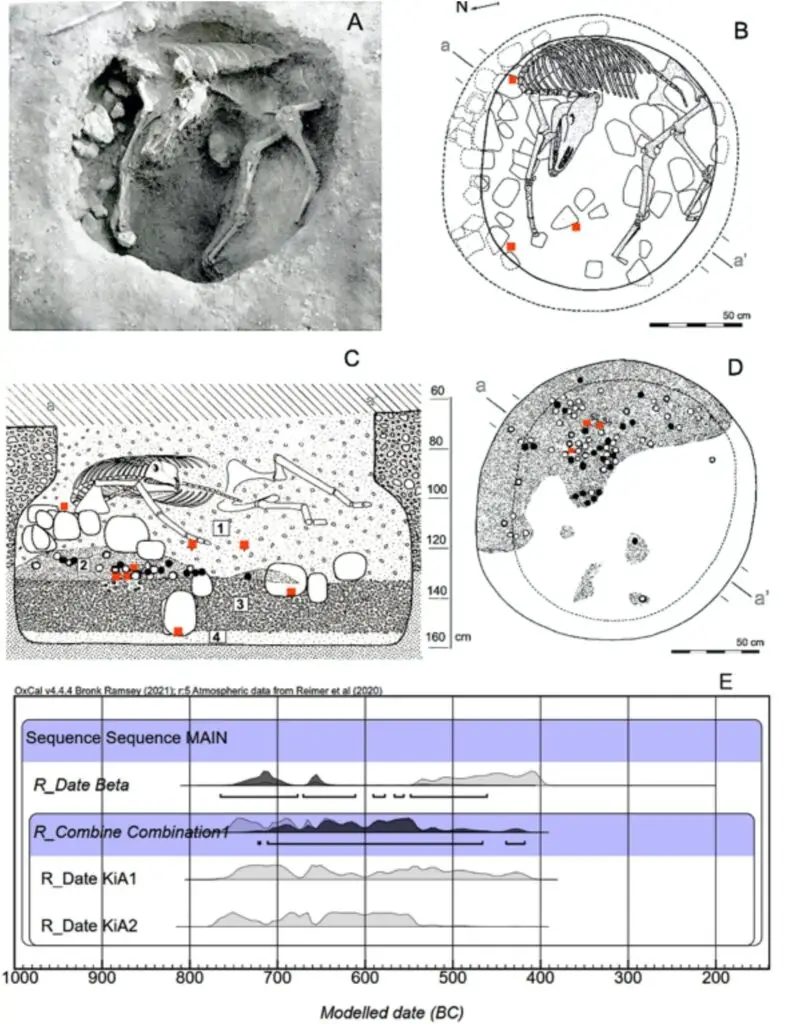

The story begins not with a grand monument or a glittering artifact, but with a pit. In 1986, during an excavation at the Hort d’en Grimau site in Castellví de la Marca, archaeologists uncovered a strange and haunting scene. Inside what was probably a silo lay the partially burnt skeletal remains of a woman. Beside her, preserved through centuries of soil and silence, were the bones of an animal no one at the time suspected would rewrite a piece of Mediterranean history.

Those bones, now kept at the Museum of Wine Cultures of Catalonia in Vilafranca del Penedès, would wait decades before yielding their full story. Only now, with modern scientific tools and a fresh set of questions, have researchers from the Prehistoric Studies and Research Seminar and the Institute of Archaeology of the University of Barcelona revealed the identity of that animal. It was a mule, and not just any mule, but the oldest documented mule in the western Mediterranean and continental Europe.

When a Mule Becomes a Messenger From the Past

The mule’s age places it between the 8th and 6th centuries BC, in the early Iron Age, long before the Roman world would leave its stamp on Europe. This period is marked by movement, exchange and the expanding web of Phoenician trade across the Mediterranean. These seafaring traders introduced donkeys to the Iberian Peninsula, bringing with them not only goods but also new knowledge and new animals.

Since a mule is a hybrid between a donkey and a mare, the dating of this one suggests something remarkable. The researchers concluded that “knowledge of hybridizing equids may have reached Europe from the Middle East earlier than previously thought.” The mule becomes, in a sense, a quiet witness to the arrival of ideas carried over waves, carried on ships, carried by the networks the Phoenicians built link by link along the coastline.

What once seemed like a simple set of animal remains is now a messenger from a distant age, speaking to the movement of people, animals and knowledge across vast distances.

Following the Clues Hidden in Bone

To unlock the mule’s identity, scientists turned to a combination of radiocarbon dating and genetic analyses. They conducted a multidisciplinary study exploring the animal on taxonomic, morphological, pathological and dietary levels. Stable isotope data helped reveal what it ate and how it lived. Each method added a new shade to the portrait.

The historical context deepened the mystery. The same site, along with nearby ones, contained material of Phoenician origin. This was not an isolated village but a place tied into a far-reaching network of trade. The Phoenicians brought exotic animals such as donkeys and chickens into Iberia. Their presence here is a sign that cultural influence and economic exchange reached further inland than many might have assumed.

And so the bones in the pit were no longer just remains. They were evidence of a world knitted together by commerce and curiosity.

An Ancient Innovation in Motion

Hybridization of equids was not done casually. It required knowledge, intention and a clear understanding of the strengths of different animals. Mules, born from a donkey and a mare, offered a powerful advantage. They could carry loads more efficiently, withstand harsher climates and resist fatigue better than horses. They were, in every sense, engineered for work.

The researchers propose that this particular mule was used for transport and fed on fodder, meaning it lived a life of labor and reliance. It may have been the product of crossbreeding between locally raised horses and imported donkeys, suggesting that people of the Iberian Peninsula experimented with hybridization themselves. But the team also acknowledges another possibility. “It could also be a mule born outside the peninsula,” they note, and upcoming genetic and isotopic analyses may solve that puzzle.

Whether native-born or imported, the mule adds weight to a broader idea. The discovery “opens the door to considering the northwestern Mediterranean as an important center for Phoenician expansion.” Until this find, the oldest known mules in Europe were dated several centuries later, during the early Roman period. This single animal pushes the timeline back dramatically.

Suddenly, early Iron Age Iberia appears not as a remote corner but as a dynamic crossroads where innovation flowed.

Why This Ancient Mule Matters

It is tempting to see ancient discoveries as small curiosities, but this mule carries far more significance than its silence might suggest. It reveals the reach of Phoenician trade, the spread of agricultural and technological knowledge and the surprising complexity of early Iberian societies. It shows that hybridization, an intentional and skilled practice, was likely known in Europe earlier than anyone had realized.

Most strikingly, it illuminates how interconnected the ancient world truly was. A single mule, found beside the remains of a woman in a forgotten pit, becomes proof that the early Iron Age was alive with movement. People traded, traveled and experimented. They exchanged animals, ideas and techniques. They shaped landscapes and cultures through choices that still echo today.

This discovery also challenges earlier assumptions. If the oldest previously known European mules came three or four centuries later, then researchers now have reason to look again, to question what else lies beneath fields and vineyards, waiting patiently for modern science to notice.

In the end, the mule from Penedès is more than the oldest of its kind. It is a reminder that history is full of stories waiting to be uncovered, stories that change how we see the past and how we imagine the world behind us. The animal stands not only as a scientific milestone but also as a testament to the curiosity and interconnectedness that have always defined human civilization.

More information: Silvia Albizuri et al, The oldest mule in the western Mediterranean. The case of the Early Iron Age in Hort d’en Grimau (Penedès, Barcelona, Spain), Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports (2026). DOI: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2025.105506