Along the rugged northern coast of Spain, the past has always spoken in fragments. Charcoal buried in ancient hearths. Bones left behind after meals long finished. And, very often, shells carried in from the sea by people who lived close to the water nearly 18,000 years ago. For decades, archaeologists have listened carefully to these remains, using radiocarbon dating to ask one simple question: when did these people live?

But the sea has a habit of whispering the wrong time.

A new international study led by the Institute of Environmental Science and Technology of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (ICTA-UAB) has revealed that some of those whispers have been slightly misleading. By refining how scientists correct radiocarbon dates from marine remains, the research sharpens our view of the Magdalenian period, a key chapter of European prehistory preserved along the Cantabrian coast. Published in the journal Radiocarbon, the study offers a more precise way to read time itself from shells, fish, and other traces of ancient coastal life.

This is not a story about rewriting history. It is about tuning the clock.

The Clock That Ticks Inside All Living Things

Radiocarbon dating works because life quietly records time while it lives. Every living organism absorbs carbon-14, a naturally occurring radioactive isotope, from its environment. Plants take it in from the air. Animals absorb it by eating plants or other animals. As long as an organism is alive, this exchange keeps its carbon-14 levels in balance with the world around it.

Death stops that exchange. From that moment on, carbon-14 begins to decay at a steady pace, losing half of its remaining amount every 5,730 years. By measuring how much carbon-14 remains in a sample, scientists can calculate how long it has been since that organism died and place it within a chronological framework.

This method has become one of archaeology’s most trusted tools. Charcoal from ancient fires, human bones, and the remains of terrestrial animals often provide clear and reliable dates. But along ancient coastlines, the story is rarely so simple.

When the Ocean Keeps Older Secrets

Many prehistoric sites along the northern Iberian Peninsula sit close to the sea. For the people who lived there during the Magdalenian period, marine resources were often part of daily life. Shells, fish, and other marine remains are sometimes the only materials left behind that can be dated.

Yet marine organisms carry a hidden complication.

The ocean does not share carbon-14 in the same way the land does. Seawater contains carbon that has already lost part of its carbon-14 through long cycles beneath the surface. As a result, marine organisms incorporate less carbon-14 than terrestrial organisms living at the same time. When they die, they begin their decay from a lower starting point.

This phenomenon is known as the marine reservoir effect, and it can make radiocarbon dates from marine remains appear several hundred years older than they truly are. Without careful correction, the sea can quietly push the past farther away than it should be.

The Art of Correcting Time

To address this problem, archaeologists rely on a global marine calibration curve that accounts for average differences between marine and terrestrial carbon-14 levels. But this global curve is not enough on its own. Local conditions matter. Ocean circulation, regional ecosystems, and time periods all influence how much carbon-14 marine organisms contain.

That is why scientists apply a local correction value known as ΔR. This factor adjusts marine radiocarbon dates to better match reality. But ΔR is not constant. It varies by region and by era, and determining the correct value is essential for reliable dating.

As Asier García-Escárzaga, who conducted the research at ICTA-UAB and the Department of Prehistory of the UAB, explains, accurate ΔR values are especially critical at sites where marine remains dominate, or when dating human populations whose diets included large amounts of marine resources. Without them, the archaeological clock drifts.

A Cave That Held Two Timelines

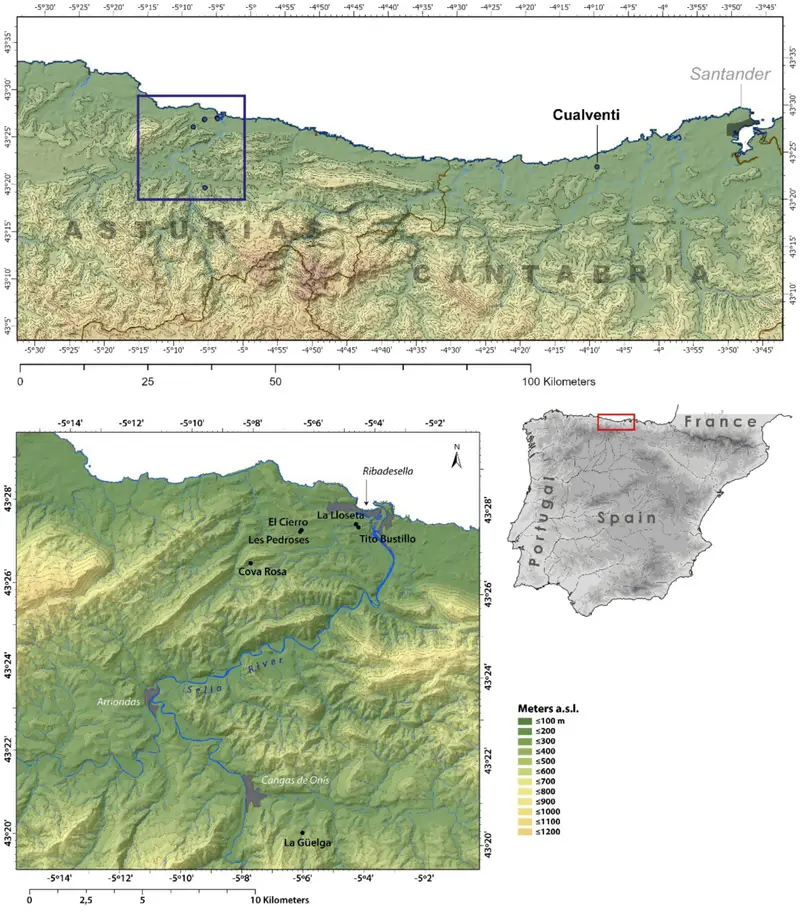

To refine these corrections for the Magdalenian period, the research team turned to a site that offered a rare opportunity. The Tito Bustillo cave in Ribadesella is famous for its rock art and Paleolithic engravings, but it also preserves something equally valuable: both marine and terrestrial remains from the same archaeological context.

By comparing radiocarbon dates from shells and other marine materials with dates from terrestrial remains recovered from the same layers, the researchers could directly measure how much the marine dates were offset. This side-by-side comparison allowed them to calculate new ΔR values specific to Magdalenian sites in the northern Iberian Peninsula dating to around 18,000 years ago.

The study brought together researchers from the universities of Salamanca and Cantabria, the Aranzadi Society of Sciences, and the Max Planck Institute in Germany, combining expertise across archaeology, environmental science, and radiocarbon analysis.

The result is a refined correction that makes marine-based radiocarbon dates significantly more precise.

Precision Without Rewriting the Past

One of the most important messages of the study is what it does not do. These new correction values do not suddenly make archaeological sites older or younger than previously believed. They do not overturn established timelines or introduce dramatic shifts in human history.

Instead, they reduce uncertainty.

As García-Escárzaga notes, this advance allows archaeologists to fine-tune the clock they use to reconstruct the history of Paleolithic populations. When dates are more precise, the gaps between events become clearer. Occupations can be distinguished more accurately. Changes in behavior, technology, or settlement patterns can be placed in better order.

In coastal regions, where marine remains are often the primary source of dating evidence, this precision can make the difference between a blurred timeline and a coherent narrative.

Seeing the Magdalenian World More Clearly

The Magdalenian period represents a crucial phase of human prehistory in Europe. Along the Cantabrian coast, it is marked by artistic expression, complex tool traditions, and long-term occupation of caves and coastal environments.

Understanding exactly when these activities occurred matters. It shapes how researchers interpret the pace of cultural change, the duration of occupations, and the relationship between people and their environment. When dates are slightly off, even by a few hundred years, connections between sites can appear weaker or stronger than they truly were.

By improving the accuracy of marine radiocarbon dating, the study helps align coastal sites more precisely with inland ones. It brings different strands of evidence into better agreement and allows archaeologists to reconstruct the Magdalenian past with greater confidence.

Why This Research Matters

This research matters because archaeology is ultimately about time. Every story of human history depends on knowing not just what happened, but when. Along ancient coastlines, where the sea provided food, materials, and pathways, marine remains are often the only voices left to speak for the past.

By refining ΔR correction values for the northern Iberian Peninsula, this study gives those voices a clearer tone. It ensures that shells and other marine remains tell time more honestly, without the quiet distortion of the marine reservoir effect.

The result is a sharper, more reliable picture of human life 18,000 years ago, one that respects the complexity of both the ocean and the people who lived beside it. In tuning the archaeological clock, the researchers have not changed the story of the Magdalenian world. They have simply helped us hear it more clearly.

Study Details

Asier García-Escárzaga et al, Bayesian estimates of the marine radiocarbon reservoir effect during the Magdalenian in northern Iberia, Radiocarbon (2025). DOI: 10.1017/rdc.2025.10175