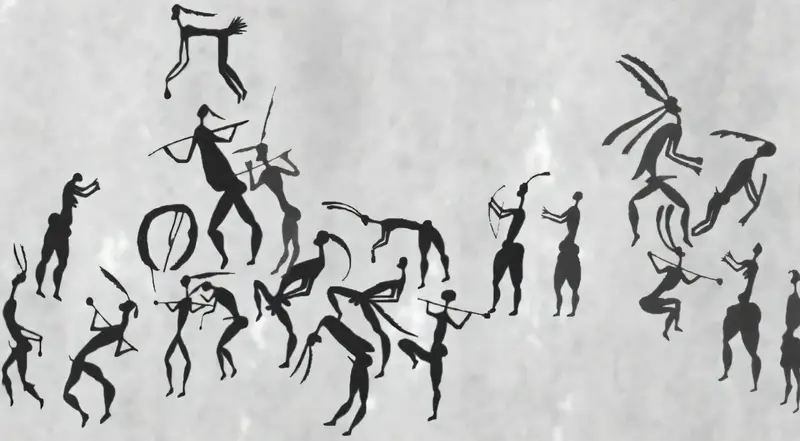

On the stone faces of southern Africa, figures bend, circle, clap, and transform. They are frozen in pigment, yet somehow still alive. For generations, these images have been admired as art. Now, they are being listened to as stories of movement, rhythm, and meaning.

In a study published in Telestes, Dr. Joshua Kumbani and Dr. Margarita Díaz-Andreu turned their attention to one of the most recurring and expressive themes in South African rock art: dance. What they found was not a single ritual frozen in time, but a living archive of cultural practices painted by the San themselves. These scenes capture healing, initiation, rainmaking, and even moments of joy that may never have been written down anywhere else.

By drawing together ethnographic sources, published studies, and the extensive SARADA database, the researchers set out to do something that had surprisingly never been done before. They systematically identified, categorized, and interpreted the different kinds of dances shown on rock walls across South Africa, treating these images not as isolated artworks but as evidence of lived experience.

The San and the Language of Movement

The San hunter-gatherers of southern Africa left behind one of the richest rock art traditions in the world. These paintings are among the most important sources for understanding how San communities organized their beliefs, ceremonies, and social life. Within this visual language, dancing appears again and again, suggesting it was central to how meaning was created and shared.

The dances shown are varied. Some are clearly ritual in nature, linked to healing or initiation. Others seem lighter, more playful, perhaps created simply for entertainment. Until now, these scenes had been noticed but not carefully compared or analyzed as a whole.

Dr. Kumbani explains that the motivation for the study came from this gap. Dancing scenes had been mentioned in earlier publications, but they had not been examined systematically from either a music archaeological or iconographic perspective. Without that deeper analysis, it remained unclear what kinds of dances were being shown and what roles they played in San society.

The researchers wanted to know whether all dances were sacred, or whether some were simply expressions of communal enjoyment. To answer that, they turned to the details painted into the rock.

Circles of Healing Painted in Stone

Among all the dance scenes identified, one stands out as the most frequently depicted: the trance dance. This ritual form of dancing appears 17 times in South African rock art, making it the most common type recorded in the study. It is most often found in KwaZulu-Natal, where repeated visual elements link the paintings to known ethnographic descriptions.

In these scenes, dancers typically move in a circle. Men dance while women clap and sing, creating a rhythmic structure that can last for hours. The rock art captures specific physical signs associated with trance dancing. Figures bend forward at the hips. Some are shown with nosebleeds, a well-known marker of trance states. Others hold dancing sticks, tools associated with ritual movement. In some images, dancers appear partially transformed into animals, becoming therianthropes that blur the boundary between human and animal.

These details matter. They allow researchers to connect what is painted on stone with what is described in ethnographic records. The repetition of these elements across different sites strengthens the interpretation that these are not symbolic abstractions, but visual records of real ceremonial practices.

Through careful categorization, the study shows that trance dances were not rare or peripheral. They were central enough to be painted again and again, suggesting their deep importance in San spiritual and social life.

Girls, Growth, and the Power of the Eland

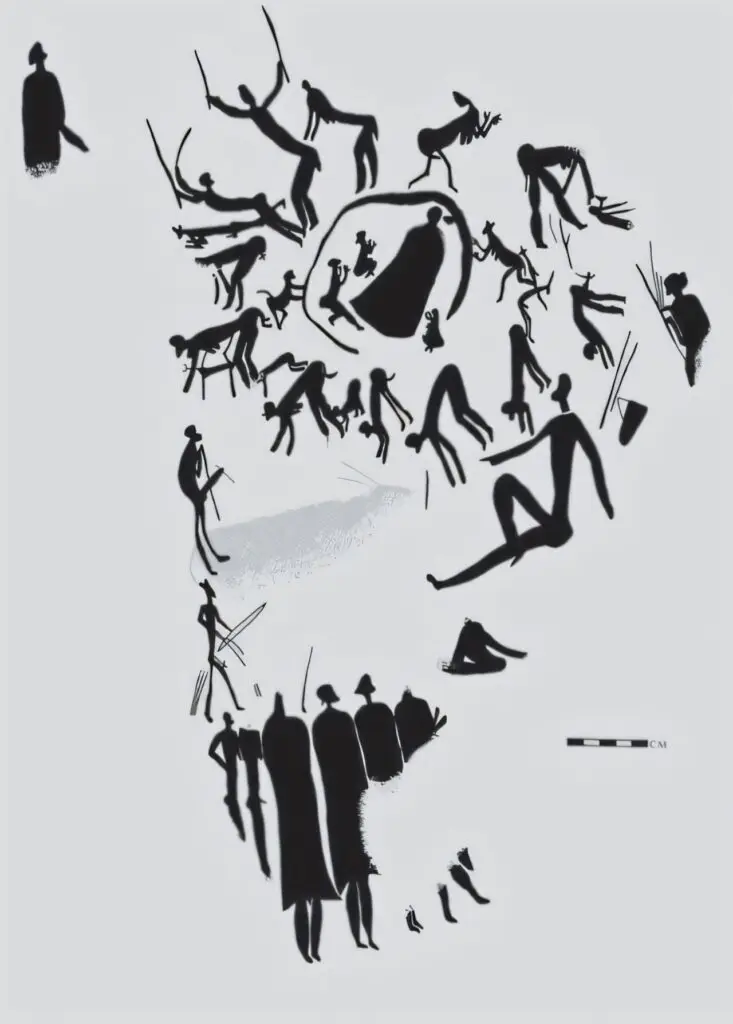

Trance dances are not the only movements preserved in pigment. Another significant category identified by the researchers is eland dances, also known as girls’ initiation dances. These ceremonies marked key transitions in life and were closely tied to ideas of fertility, growth, and social belonging.

One particularly striking example comes from Namahali, a site in the Free State. Here, the rock art depicts a dynamic scene that appears to show two distinct groups engaged in different but possibly connected activities.

According to Dr. Kumbani, one group consists of women bending forward. This posture, combined with the absence of back aprons, suggests a ritual context linked to girls’ initiation ceremonies. In such dances, women played a central role, guiding younger members of the community through an important rite of passage.

The scene does not stop there. A second group is shown carrying implements identified as digging sticks. These tools have layered meanings. Based on the Bleek and Lloyd (1911) transcripts, digging sticks were used by women during rainmaking dances and were also essential for gathering tubers. Their presence in the painting suggests that the dance may have combined multiple layers of meaning, linking initiation, subsistence, and environmental balance.

At Namahali, the rock wall becomes a stage where different aspects of San life intersect, captured in motion rather than words.

The Silence Around Male Initiation

While female initiation dances appear relatively often, one absence stands out. Male initiation rituals are rarely depicted in South African rock art. This absence raises questions that the researchers openly acknowledge.

Dr. Kumbani notes that the reasons for this are not entirely clear. Several explanations are possible, but one stands out as particularly compelling. It may be that men deliberately kept their initiation ceremonies secret, choosing not to record them visually. If so, the silence on the rock walls is itself a meaningful cultural statement.

This contrast between what is shown and what is hidden reminds us that rock art is not a complete record of San life. It is a selective archive shaped by cultural choices about what could be shared, remembered, or displayed.

More Than Ritual: Dancing for Joy

One of the key questions driving the study was whether all dances depicted in South African rock art were ritual in nature. The answer appears to be no.

While many scenes clearly relate to healing, initiation, or rainmaking, others do not show obvious ritual markers. These dances may have been performed simply for entertainment, moments of communal enjoyment that were meaningful enough to paint but not tied to formal ceremonies.

This possibility expands how we understand San rock art. It suggests that the painters were not only recording sacred moments but also celebrating everyday expressions of movement and rhythm. Dancing, in this sense, was part of life in all its forms, from the deeply spiritual to the joyfully ordinary.

Why These Painted Dances Matter Today

Rock art is one of the few ways we have to access the inner life of the San as they experienced it themselves. Written records often come from outsiders, filtered through different cultural lenses. The paintings, by contrast, were made by the San, for the San, using their own visual language.

By systematically cataloging and categorizing dance scenes, Dr. Kumbani and Dr. Díaz-Andreu have given researchers a clearer framework for interpreting what these images show and why they matter. Their work strengthens methodological approaches to studying rock art and demonstrates how ethnographic information can be used carefully and responsibly to interpret ancient images.

The study also opens the door to future research. San rock art exists beyond South Africa, extending into regions such as Namibia. The researchers hope to expand their analysis across southern Africa, building a broader picture of how dance, belief, and community were expressed through rock art.

At its heart, this research reminds us that these paintings are not static relics. They are records of moving bodies, clapping hands, bending backs, and transformed spirits. They show that long before music was written down, it was danced onto stone.

Study Details

Margarita Díaz-Andreu et al, Exploring Dance Scenes in South African Rock Art: From Kwazulu-Natal to the Western Cape, Telestes (2025). DOI: 10.19272/202514701002