To imagine daily life in Ancient Egypt is to step into a world shaped by the rhythm of a river. The Nile was not merely water flowing through a desert—it was the very artery of survival. It dictated the seasons, determined the harvests, and gave life to villages that stretched along its fertile banks. For the ordinary Egyptian, every dawn was tied to its cycles: when the river rose, crops would flourish; when it failed, hunger stalked the land.

While pharaohs and pyramids dominate modern imagination, the true story of Egypt is found not in royal tombs but in mudbrick houses, bustling markets, irrigated fields, and the laughter of children playing near the Nile. Ordinary Egyptians—the farmers, fishermen, craftsmen, and servants—were the silent majority who built the civilization that endured for over three thousand years. Their lives were not as gilded as the pharaoh’s, but they were no less meaningful. Their stories are written in pottery shards, in humble graves, and in the walls of houses preserved in desert sands.

To understand Ancient Egypt is not only to study kings and gods, but to peer into the daily rhythms of its people—how they worked, loved, struggled, and dreamed.

The Rhythm of the Seasons

Life in Egypt was organized around three great seasons, each tied to the flooding of the Nile. This natural calendar was as predictable as the sunrise, and for ordinary people it meant survival.

The year began with Akhet, the season of inundation. From June to September, the Nile swelled with floodwaters that deposited dark, fertile silt across the fields. Farmers could not work their land during this time, so many were conscripted into building projects—digging canals, maintaining dikes, or even hauling stone for temples and pyramids.

Next came Peret, the season of growth, from October to February. As the waters receded, farmers sowed barley, wheat, flax, and vegetables. With wooden plows pulled by oxen, they scratched lines into the soil, then pressed seeds into the earth with their bare feet. Families worked side by side, children scattering grain while parents guided animals through the fields.

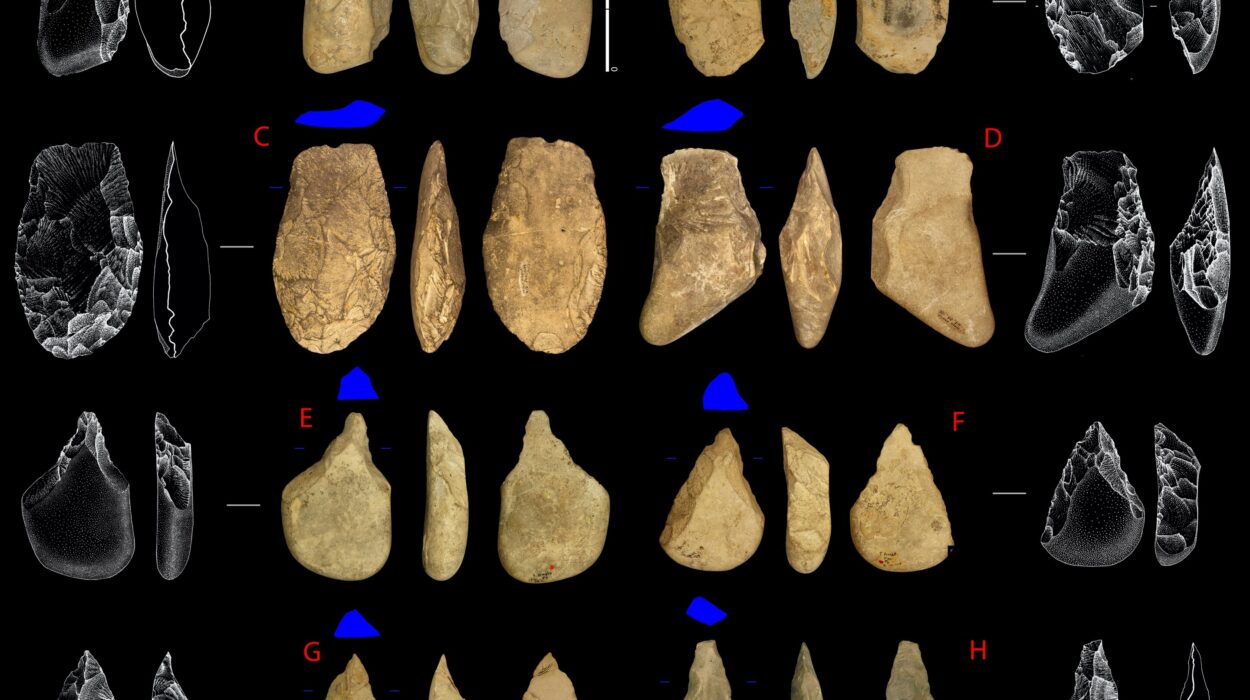

Finally, there was Shemu, the harvest season, from March to May. Families reaped their crops with flint sickles, singing as they cut golden sheaves of grain. Villagers celebrated with feasts, music, and offerings to the gods who made the cycle possible.

The cycle was so reliable that Egyptians believed it reflected cosmic order, ma’at—the divine balance of the universe. To disrupt the Nile’s rhythm would be to invite chaos, a fear that haunted both kings and commoners.

Homes of Mud and Sunlight

Ordinary Egyptians did not live in palaces of stone, but in modest houses built from mudbrick. These sun-dried bricks, made from Nile silt and straw, were cheap and plentiful. A typical house might have two or three rooms, with a flat roof where families slept on warm nights.

Inside, life was simple. The floors were hard-packed earth, sometimes covered with mats. There was little furniture beyond low stools, reed mats, and perhaps a wooden chest for storing clothing. Clay lamps burned animal fat to light the darkness, filling homes with a smoky glow.

Kitchens were usually outdoors, with clay ovens for baking bread. Women ground grain with heavy stones, kneading dough to bake into flat loaves that formed the staple of every meal. Children fetched water from the Nile or nearby wells, carrying jars balanced on their heads.

Houses were clustered tightly in villages, connected by narrow alleys where donkeys brayed, dogs barked, and neighbors greeted one another. Life was communal; doors were often left open, and sounds of conversation and work filled the air.

Though simple, these homes were full of warmth—families ate together, shared stories by lamplight, and relied on one another in both hardship and joy.

Food: Bread, Beer, and Onions

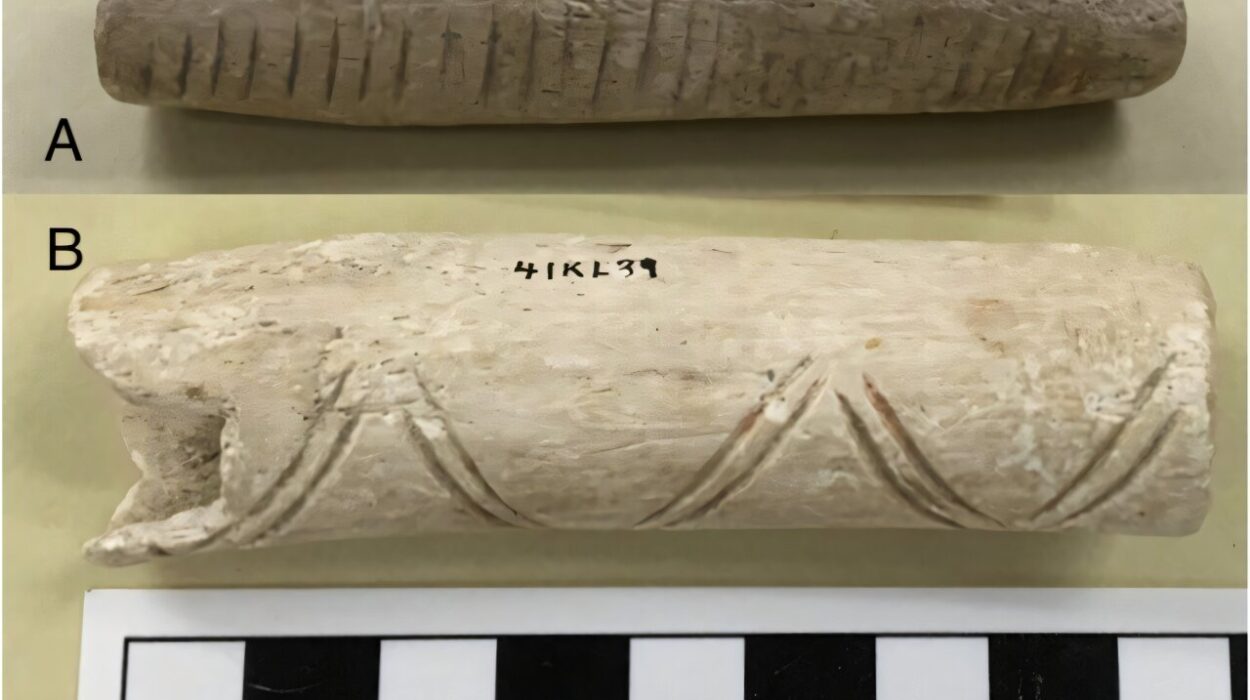

The Egyptian diet was humble but hearty. Bread was the cornerstone of every meal, baked from emmer wheat or barley. Women spent hours grinding grain into flour, mixing it with water, and baking it in clay ovens. The bread was dense, sometimes gritty with sand from the grinding stones, which wore down teeth over time.

Beer, brewed from fermented barley, was the second staple. Thick and nutritious, it was drunk by men, women, and children alike. It provided hydration in a land where clean water could be scarce and carried a mild buzz that made daily labor more bearable.

Vegetables such as onions, leeks, garlic, and cucumbers were common, along with lentils and beans. Dates and figs provided sweetness, while honey—rare and precious—was reserved for special occasions. Meat was a luxury for ordinary people, usually eaten only during festivals or special feasts. Fish from the Nile, however, was more common, caught with nets or simple hooks.

Meals were shared, eaten with hands rather than utensils. To sit with family, tearing bread, dipping it into stews, and sipping beer, was one of life’s simplest and most enduring pleasures.

Clothing and Appearance

In a land of blazing sun, clothing was light and simple. Men wore kilts of linen, while women wore sheath dresses held up by straps. Linen, made from flax, was the most common fabric, ranging from coarse for peasants to fine, almost transparent cloth for the wealthy.

Children often wore little or no clothing until adolescence, their heads shaved to prevent lice, with a small lock of hair left at the side—the “sidelock of youth.” Adults sometimes shaved their heads as well, wearing wigs made of human hair or plant fibers to keep cool and stylish.

Jewelry was popular even among ordinary people. Beaded necklaces, amulets, and simple bracelets added color to daily attire. Amulets were more than decoration; they were believed to protect against evil spirits and bring good fortune.

Cosmetics were a part of daily life for both men and women. Eyes were lined with kohl, made from galena, not only for beauty but also to reduce glare from the sun and ward off eye infections. Red ochre colored lips and cheeks, while perfumed oils softened skin dried by desert winds. In a culture that valued cleanliness, bathing in the Nile or in basins at home was a regular practice, accompanied by scented oils that replaced soap.

Work and Labor

For most Egyptians, life was work. The majority were farmers, bound to the cycles of planting and harvest. When not tending fields, they were called to labor for the state—building temples, repairing canals, or serving in work crews that hauled stone for monuments.

Craftsmen formed another vital group: potters, weavers, carpenters, and metalworkers whose skills supported daily life. Their workshops echoed with the tapping of chisels, the whirring of potter’s wheels, and the clatter of looms.

Fishermen and hunters provided food, while traders carried goods along the Nile in wooden boats. Servants worked in wealthier households, grinding grain, cleaning, and caring for children.

Women played an essential role in this economy. In addition to managing households, they worked in weaving, brewing, and farming alongside men. While pharaohs and nobles wrote their names in stone, it was the labor of these ordinary people that sustained Egypt’s grandeur.

Family and Children

Family was the heart of Egyptian life. Marriage was simple, often beginning with a couple moving in together. Love poetry written on papyrus and pottery fragments shows that affection and romance were valued as much in the Nile Valley as anywhere else.

Children were cherished, considered blessings from the gods. They spent their early years naked, playing with toys made of clay, wood, or woven reeds. Dolls, balls, and little animal figurines brought laughter to dusty courtyards. Parents taught children by example—boys learned farming, fishing, or crafts from their fathers, while girls learned weaving, cooking, and household management from their mothers.

Education was limited for most. Only boys destined for scribal work or government positions attended schools, where they learned to read, write, and calculate under strict discipline. For the majority, life skills were learned through family and community.

Despite hardships, the warmth of family bonds shines through the fragments of history—letters, tomb inscriptions, and art all speak of affection between parents and children, husbands and wives.

Religion in Daily Life

Religion was woven into every breath of Egyptian existence. Ordinary people prayed to the gods for good harvests, healthy children, and protection from illness. Shrines stood in homes, where offerings of bread, beer, or incense were made.

The pantheon was vast. Hathor, goddess of love and music, was adored by women. Taweret, the hippopotamus goddess, guarded childbirth. Bes, a dwarf-like deity, protected homes and frightened away evil spirits. Ordinary Egyptians may not have had the wealth to dedicate temples, but they carried amulets, sang hymns, and left offerings at local shrines.

Funerary beliefs also shaped daily life. The promise of an afterlife, where fields of plenty awaited, gave meaning to struggles. Even the poorest sought proper burials, wrapping their dead in linen and placing simple goods—pottery, food, or amulets—in graves to accompany them beyond death.

Leisure and Entertainment

Though life was hard, Egyptians knew how to find joy. Music, dance, and games were central to leisure. Flutes, harps, and percussion instruments accompanied festivals, while dancers and acrobats entertained crowds.

Board games were popular pastimes. Senet, played on a grid of squares with small pieces, was more than entertainment—it symbolized the journey of the soul through the afterlife. Children played with spinning tops, balls, and dolls, while adults gathered to gamble with dice or enjoy storytelling.

Festivals brought communities together. The Nile’s flooding was celebrated with feasts, beer, and dancing. Religious holidays honored gods with processions, music, and offerings. In these moments of joy, the hardships of daily labor faded, replaced by laughter and community spirit.

Medicine and Health

Illness and injury were constant challenges. Egyptian medicine blended practical remedies with spiritual healing. Doctors, known as sunu, used herbs, honey, and animal products to treat wounds and diseases. Honey, with its antibacterial properties, was applied to cuts, while garlic was used for infections.

Magic was equally important. Spells were recited to drive out illness believed to be caused by spirits. Amulets were worn to ward off disease. This combination of practical and supernatural reflects the Egyptian worldview, where the physical and spiritual were inseparable.

Dental problems were widespread due to gritty bread, and life expectancy was short by modern standards—many died before forty. Yet evidence from mummies shows attempts at surgery, prosthetics, and advanced treatments that demonstrate remarkable medical knowledge for their time.

Conclusion: The Real Builders of Egypt

When we think of Ancient Egypt, we picture pyramids, mummies, and golden treasures. But behind the monuments stood millions of ordinary people whose hands and hearts sustained this civilization. They lived in mudbrick houses, ate bread and onions, worked under the desert sun, prayed to household gods, and found joy in music and laughter.

Their lives were not recorded in hieroglyphs carved into temple walls, but in the wear on their bones, the toys of their children, the bread ovens still standing in abandoned villages. They were farmers, mothers, craftsmen, fishermen, servants—people who loved, toiled, and dreamed beneath the eternal gaze of the Nile.

To understand Ancient Egypt is to honor these lives, for it was they, not the kings alone, who built one of the world’s greatest civilizations. Their daily struggles and joys remind us that history is not only the story of rulers and battles, but of ordinary human beings, whose lives, though humble, shaped the world.