Thousands of years ago, before skyscrapers and smartphones, before metal tools or maps, something extraordinary stirred in the dry soils of the Sonoran Desert.

Not an empire. Not a war. Not a monument.

A seed.

Maize—humble, golden, genetically wild—arrived in the Tucson Basin during what archaeologists call the Early Agricultural Period (EAP). But how it got there, and who carried it, has been a long-standing mystery that has divided scholars for decades.

Now, a new study by bioarchaeologist Dr. James Watson and his team is rewriting that story with remarkable precision. Published in the journal American Antiquity, the research weaves together three threads of evidence—projectile points, mortuary practices, and bioarchaeology—to reveal the fingerprints of small-scale migrations that likely brought maize northward from Mesoamerica. The tale they tell is not one of conquest, but of quiet cultural exchange, resilience, and identity planted in unfamiliar soil.

A Tale of Two Hypotheses

In archaeology, every artifact whispers a theory, and for years, two competing ideas have dominated the conversation about how maize arrived in what is now southern Arizona.

One theory suggests that maize and its sister crops—beans, squash—traveled with migrating farming communities from Mesoamerica around 4,500 years ago. These migrants didn’t arrive en masse like an invading army. Instead, they trickled in, integrating with local hunter-gatherers.

The other hypothesis paints a subtler picture: that maize spread not with people, but through people—by way of long-distance trade networks, cultural borrowing, and neighbor-to-neighbor exchange.

For decades, the evidence seemed to support both stories. But Dr. Watson and his colleagues believed there was more to find beneath the desert surface. And they were right.

Stone Points and Silent Stories

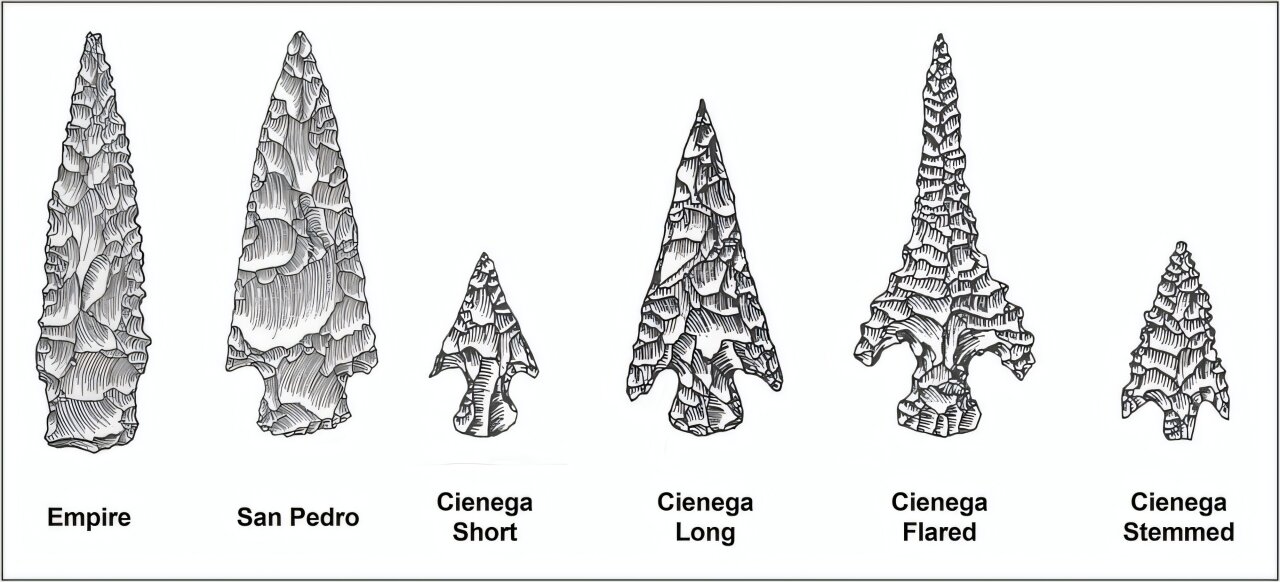

To understand the deep past, Watson’s team turned to an unlikely source of evidence: projectile points—stone arrowheads and spear tips that once served as tools, weapons, and, as it turns out, cultural calling cards.

In the archaeological layers of the Sonoran Desert, they found four distinct types of points. Two, in particular, stood out: the Empire point and the San Pedro point.

Empire points were long, thick, and carefully serrated—crafted with a precision that hinted at origins beyond the local traditions. They dominated one key site: Las Capas, an ancient village nestled near the Santa Cruz River. San Pedro points, by contrast, were shorter, broader, and far more common at nearby sites.

Here’s where it gets intriguing: after a temporary abandonment of Las Capas, the people who returned began making San Pedro-style points, not Empire ones. This abrupt shift, the researchers suggest, points to a new cultural identity—either because the migrants had assimilated with local groups or because they were replaced by them.

“It’s a subtle but powerful signal,” explains Dr. Watson. “Those projectile points aren’t just tools. They’re traditions—passed down, taught, and shared. Their sudden disappearance suggests a change in who was calling that place home.”

Burying the Dead, Uncovering Identity

But stone tools only tell part of the story. To go deeper, Watson’s team turned to the dead—their bodies, their graves, their rituals.

In prehistory, how a community buries its dead often says more about its beliefs than its buildings ever could. At sites across the Tucson Basin, local burials were strikingly consistent: most individuals were laid to rest in flexed positions, curled like sleeping children. Pigmentation—using red ocher or hematite—was rare. Grave goods were sparse but symbolic: shells, tools, sometimes a projectile point tucked beside a man’s bones.

But at other sites, especially La Playa—linked to the same Empire points as Las Capas—the story was different. There, bodies were placed prone, extended, or in varied postures. Pigmentation was common. The diversity of burial practices spoke of a different worldview, perhaps even a different origin.

These weren’t just stylistic differences. They were expressions of identity—of belonging, belief, and memory. And they strongly suggested the presence of non-local groups who carried not just maize seeds but rituals, customs, and cosmologies with them.

DNA in the Dust: What Bones Remember

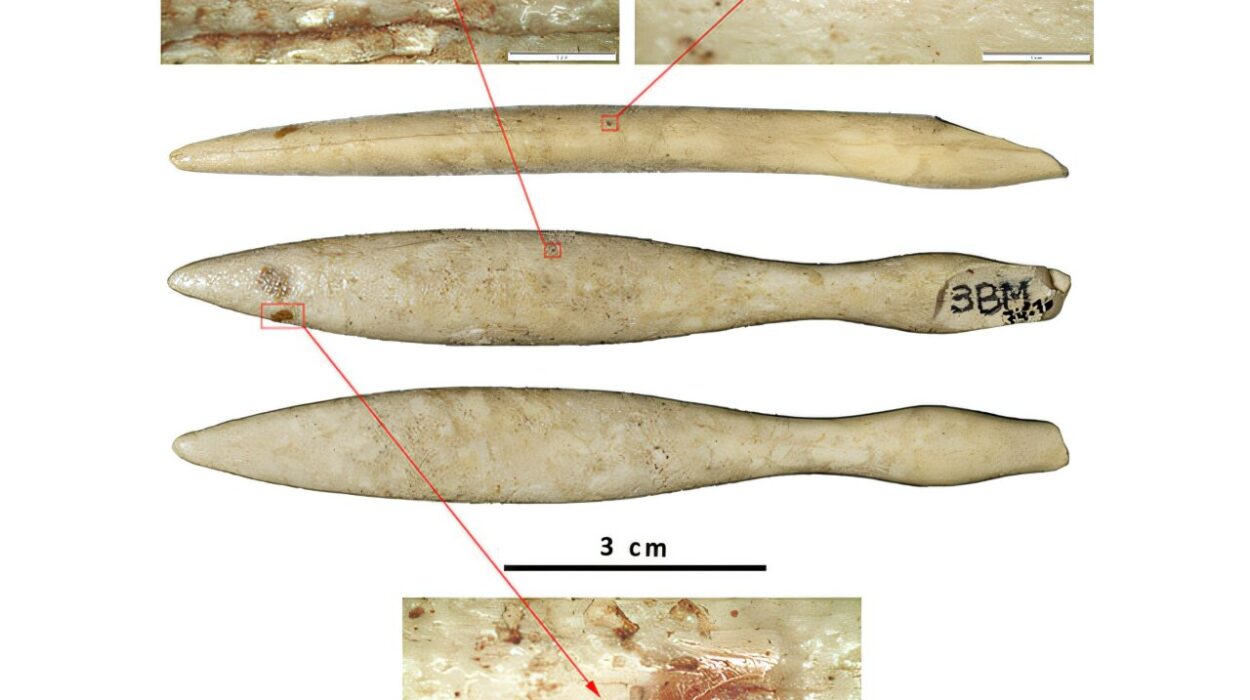

Still, Watson and his colleagues weren’t content to stop at stones and skeletons. They also turned to bioarchaeology—the study of ancient human remains—to look for genetic fingerprints of migration.

What they found was subtle, but telling. Male skeletons from the EAP showed greater genetic diversity than female ones. This pattern, researchers believe, reflects exogamous marriage practices, where males were more likely to marry—and migrate—outside their natal groups.

“Increased male gene flow often indicates male-dominated movement,” says Watson. “It aligns with the other lines of evidence suggesting small-scale male-led migrations introducing maize into the region.”

These weren’t massive population shifts, like those that would define later epochs. They were trickles—fathers, sons, brothers—moving northward, bringing with them seeds and stories, changing the destiny of the desert one field at a time.

The Role of Water and Timing

Timing, as always in archaeology, is everything. The arrival of maize coincided with a rare climatic gift in the Sonoran Desert: water.

The period when maize appears in the archaeological record was not a time of drought, but one when rainfall was relatively abundant. Rivers like the Santa Cruz flowed more freely, carving fertile floodplains. This moisture would have made early farming feasible—and tempting.

“Maize enters the Sonoran Desert at a time when water was apparently plentiful,” says Watson. “That likely aided in its spread and in people’s willingness to invest in agriculture.”

In a desert, water is life. And in this case, it may have been the catalyst that allowed a foreign crop to take root in a new land—and with it, a new way of life.

A Uniquely Sonoran Story?

One of the most surprising takeaways from Watson’s study is how localized this pattern of migration seems to be.

While maize eventually blanketed much of North America, Watson notes that there’s no clear evidence of similar migration-linked introductions of maize in other northern regions during this period.

The Sonoran Desert, then, may represent a unique cultural corridor—one where migration, climate, and innovation aligned to create the continent’s first agricultural societies.

And the legacy of those ancient farmers didn’t stop in Tucson. There’s growing evidence that some San Pedro phase farmers eventually migrated even farther north to the Colorado Plateau, laying the foundation for the Western Basketmaker II culture—one of the early ancestors of the Ancestral Puebloans.

The Human Story Beneath Our Feet

Science, at its best, doesn’t just give us data. It gives us context. It teaches us not only what happened, but what mattered.

Watson’s study is a powerful reminder that agriculture didn’t begin with machines or manifestos. It began with risk, with travel, with trust in the land and in strangers. The first farmers of the Sonoran Desert weren’t conquering heroes. They were likely migrants looking for better lives—people who carried seeds and memories in the folds of their clothing, who dug into dry earth with hope.

And while maize is now a global crop—fueling economies, diets, and politics—it began as a whisper in the desert, a quiet promise planted by human hands.

Reference: James T. Watson et al, Small-Scale Migrations among Early Farmers in the Sonoran Desert, American Antiquity (2025). DOI: 10.1017/aaq.2024.78