Few artifacts inspire as much intrigue, fascination, and controversy as the so-called “crystal skulls.” These enigmatic objects—carved from blocks of clear or milky quartz into the shape of human skulls—have captivated imaginations for more than a century. They are shrouded in legends that speak of lost civilizations, mystical powers, and even extraterrestrial connections. For some, the skulls are sacred relics passed down by ancient peoples with wisdom far beyond our own. For others, they are clever fakes born of the human hunger for mystery.

Regardless of their authenticity, crystal skulls occupy a curious place in both science and myth. They straddle the line between archaeology and folklore, between history and hoax. To explore their story is to explore not only the objects themselves but also the deep human need to find wonder in the past.

First Glimpses in the Western World

The skulls first came to light in the mid- to late-19th century, a time when archaeology was still a young and romantic discipline. Explorers and collectors roamed the jungles of Central America, hungry for treasures from the Maya and Aztec civilizations. Amid the relics of temples and tombs, tales began to surface of crystal skulls—objects said to be found buried in ruins, gleaming like glass yet carved with uncanny skill.

Perhaps the most famous story centers around Frederick Albert Mitchell-Hedges, a British adventurer. In the 1920s, he claimed to have discovered a crystal skull at the Maya site of Lubaantun in Belize. The artifact, later called the “Mitchell-Hedges Skull,” was said to be so finely carved that it defied explanation. According to Mitchell-Hedges, the skull was ancient, created by a civilization with knowledge surpassing anything modern science could replicate.

Though romantic, the tale was riddled with inconsistencies. Records showed that the skull was purchased at auction in London in 1943, not unearthed in Belize. Still, the story stuck. To believers, the Mitchell-Hedges Skull was a key to forgotten knowledge. To skeptics, it was simply one of many mysterious artifacts whose origins had been embellished.

Legends of Ancient Wisdom

The allure of the crystal skulls lies not only in their craftsmanship but in the legends woven around them. Among the most enduring is the tale of the “thirteen skulls.” According to popular lore, there exist thirteen ancient crystal skulls, each imbued with wisdom and power. When brought together, these skulls would reveal secrets of the universe, offering humanity guidance in times of crisis.

Proponents of this legend suggest that the skulls were created by the Maya, the Aztecs, or even more ancient civilizations like Atlantis. Some stories go further still, claiming the skulls are gifts from extraterrestrials who visited Earth in antiquity. Their flawless carving, believers argue, could not have been achieved with primitive tools.

These legends grew in popularity in the 20th century, fueled by books, documentaries, and later Hollywood films. They resonated with a public hungry for mystery, particularly during the New Age movement of the 1970s and 1980s, when crystals were widely associated with healing, energy, and spiritual awakening.

The Craftsmanship of the Skulls

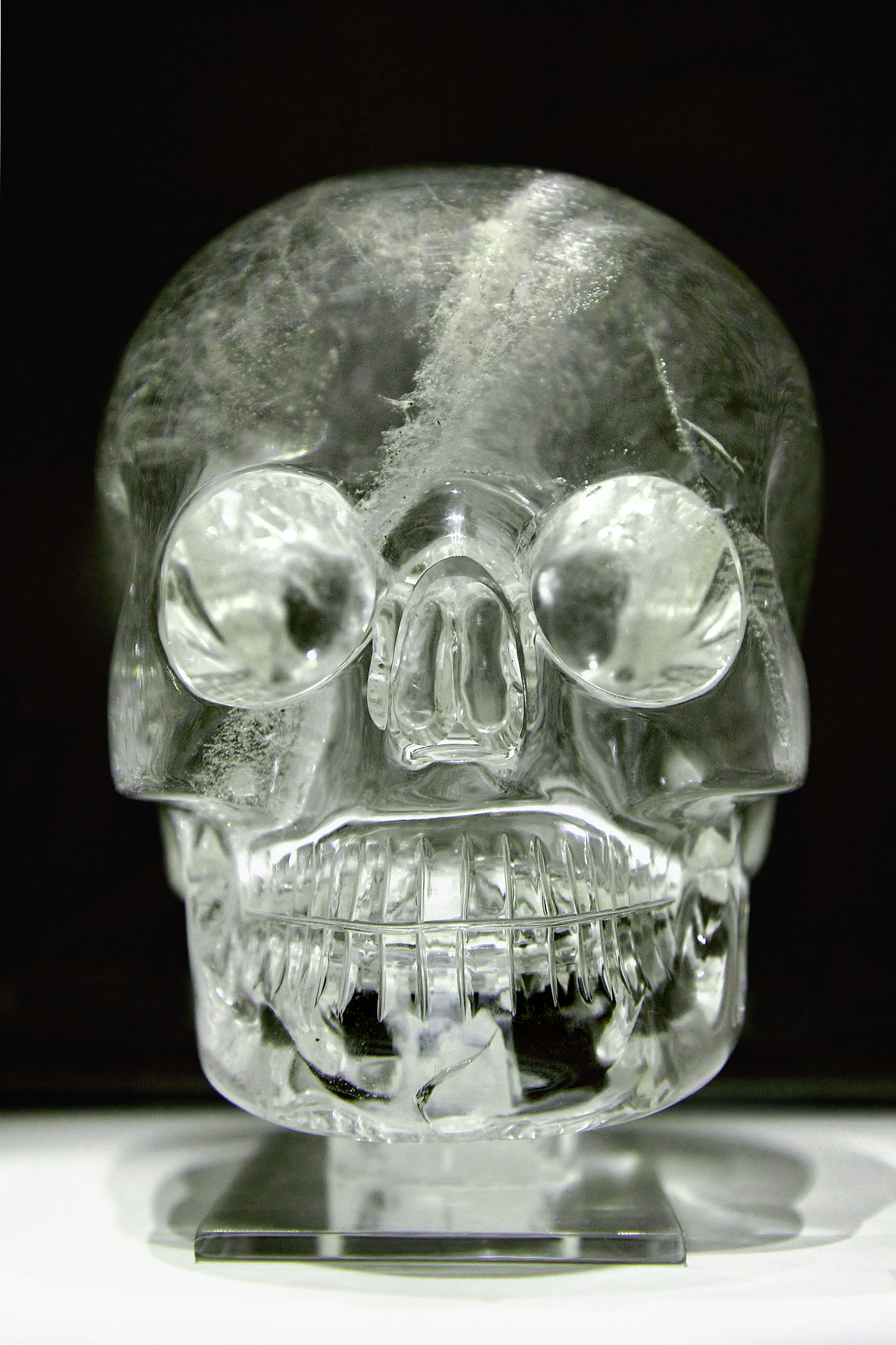

To understand the fascination with crystal skulls, one must consider their artistry. Quartz crystal is a notoriously difficult material to work with. It is hard, brittle, and prone to fracturing under pressure. Carving it into complex shapes requires patience, skill, and the right tools. The human skull, with its intricate curves, cavities, and proportions, presents an especially challenging subject.

Some skulls, like the Mitchell-Hedges Skull, display remarkable polish and symmetry. The jaw is separate and movable. Light refracts beautifully through the clear crystal, creating an almost lifelike presence. Others are cruder, with rougher surfaces and less accurate proportions.

To admirers, the perfection of the finest skulls seemed to suggest a technology unknown to the ancients. How, they asked, could pre-Columbian artisans without metal tools achieve such precision? To skeptics, the answer was simpler: the skulls were not ancient at all. They were the work of modern lapidaries, crafted using advanced equipment and then passed off as relics.

Scientific Investigations

By the late 20th century, crystal skulls had become so famous that scientists began to study them in detail. Researchers from institutions such as the British Museum and the Smithsonian Institution examined several prominent examples using electron microscopy and other techniques. Their findings were illuminating.

Microscopic analysis revealed tiny marks consistent with rotary wheels and modern abrasives, tools unavailable to pre-Columbian peoples. In some cases, traces of carborundum, a synthetic abrasive developed in the late 19th century, were found. The style of carving also bore little resemblance to known Mesoamerican art traditions.

The conclusion was difficult to avoid: most, if not all, of the crystal skulls in museums and private collections were modern fabrications. Many likely originated from lapidary workshops in 19th-century Europe, particularly in Germany, where artisans in Idar-Oberstein were renowned for their skill with quartz and other stones. These workshops could have produced skulls for sale to collectors eager for exotic artifacts, blurring the line between genuine archaeology and imaginative fraud.

The Clash of Belief and Evidence

Despite these findings, belief in the skulls’ mystical origins has not faded. For those who see them as symbols of ancient wisdom, scientific reports are dismissed as narrow or incomplete. They argue that absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, that science cannot always measure the intangible qualities of sacred objects.

This clash between science and belief is part of what keeps the crystal skulls compelling. They are not merely artifacts; they are mirrors reflecting our own desires. To some, they represent proof that lost civilizations were more advanced than we imagine. To others, they offer a connection to spiritual realms. And to skeptics, they are cautionary tales about the dangers of wishful thinking in archaeology.

Crystal Skulls in Popular Culture

Crystal skulls have long since escaped the confines of museums and private collections. They have become icons of popular culture, appearing in novels, television shows, and films. Most famously, they took center stage in the 2008 film Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. While the movie blurred fact and fiction, it introduced the legend to a new generation.

New Age spirituality also embraced the skulls, with practitioners claiming they emit healing energies or act as conduits for higher consciousness. Some crystal skull enthusiasts hold gatherings where skulls are displayed, meditated upon, and “activated.” Whether or not one accepts these claims, they speak to the enduring human need to find meaning in objects that seem otherworldly.

Why Skulls?

One of the most intriguing questions is why the human skull was chosen as the form for these carvings. The skull is a powerful symbol across cultures. It is both a reminder of mortality and a representation of the seat of the mind. In Mesoamerican art, skulls appear frequently in depictions of deities, sacrifices, and cycles of death and rebirth.

For Europeans of the 19th century, skulls also carried fascination. They evoked curiosity about life, death, and the mysteries of existence. By carving skulls from crystal—material long associated with purity, energy, and eternity—artisans created objects that resonated with universal symbolism. Whether intended as hoaxes or as curiosities, the crystal skulls tapped into deep cultural archetypes.

The Real Archaeological Record

It is important to distinguish between the legends of the crystal skulls and the authentic achievements of Mesoamerican civilizations. The Maya, Aztecs, and their neighbors produced remarkable works of art in stone, jade, obsidian, and bone. They built cities of astonishing complexity, developed sophisticated calendars, and made advances in mathematics and astronomy.

Skull imagery was indeed significant in their cultures. The Aztec tzompantli, or skull rack, displayed rows of human skulls from sacrifices, symbolizing power and the cyclical nature of life. Carvings of skulls appear in temples and codices, reflecting themes of death, fertility, and cosmic renewal.

But no verified pre-Columbian crystal skulls have ever been found in controlled archaeological excavations. The absence of such discoveries strongly suggests that the famous quartz skulls in circulation today are not genuine products of ancient Mesoamerican artistry.

The Psychology of Belief

Why, then, do crystal skulls continue to inspire belief despite the evidence? Part of the answer lies in the psychology of mystery. Humans are storytelling creatures. We are drawn to objects that promise hidden meanings or secret histories. When confronted with something as strange as a crystal skull, our imaginations leap to fill the gaps.

Belief in the skulls also reflects a longing for connection to a deeper past, one in which human civilizations were wiser or more in tune with the cosmos. In an age of rapid technological change and environmental crisis, the idea of lost wisdom holds powerful appeal. Whether through tales of Atlantis, extraterrestrials, or ancient shamans, crystal skulls invite us to dream of knowledge beyond our reach.

The Continuing Journey

The story of the crystal skulls is not finished. New skulls continue to appear in markets and collections, each accompanied by its own origin tale. Scholars continue to test and analyze them, while spiritual seekers gather to meditate on their energies. They remain objects suspended between worlds: part archaeology, part myth, part modern invention.

Perhaps that is their real power. Whether ancient or modern, authentic or fraudulent, crystal skulls reflect our hunger for mystery, our fascination with life and death, and our restless search for meaning. They remind us that history is not only about facts and artifacts—it is also about imagination and belief.

Conclusion: Between Stone and Story

So what are the crystal skulls? From a scientific standpoint, they are almost certainly modern creations, carved with tools unavailable to the ancient peoples they are often attributed to. From a cultural standpoint, however, they are something far larger. They are myths made solid, stories crystallized in quartz.

Their alleged origins—whether in Maya temples, Atlantean halls, or alien spacecraft—say less about the skulls themselves than about us. They reveal our yearning to believe that the past holds secrets capable of transforming the present. They show how easily mystery can blossom in the absence of certainty.

The crystal skulls may not be keys to cosmic wisdom, but they are keys to understanding human imagination. And perhaps that is why they endure—not as relics of lost civilizations, but as monuments to the enduring human need for wonder.