The story begins quietly, with bones laid to rest along the Nile River Valley, in a landscape that once belonged to ancient Nubia and now lies within present-day Sudan. For centuries, these remains held their silence. Archaeologists studied them, cataloged them, measured them, and moved on. But hidden on the skin of some of these long-buried people was a message no one had fully heard before. Only now, with new ways of seeing, has that message begun to emerge.

Ancient Nubians who lived between the 7th and 9th centuries tattooed the cheeks and foreheads of their infants and toddlers. The idea alone stops time for a moment. Tattooing, something many people today associate with adulthood, choice, and personal expression, was being placed on the faces of children who had barely learned to walk, and in some cases, had barely entered the world at all.

This discovery did not come from a single extraordinary mummy or a chance find. It emerged slowly and carefully from a systematic survey of more than 1,000 human remains examined across three archaeological sites. Each individual added a fragment to a much larger story, one that had been waiting for the right moment to be told.

When Tattoos Were More Than Decoration

Tattoos have always carried meaning. Across human history, they have been used to mark identity, religious belief, belonging, and personal experience. Archaeological evidence suggests that tattooing practices stretch back at least 5,000 years, weaving ink into the story of humanity itself.

In ancient Nubia, tattoos were already a subject of fascination by the 1800s. Early archaeologists noticed faint markings on mummified skin and began to document them. But time had taken its toll. Skin darkened. Ink faded. Subtle details slipped beyond the reach of the naked eye. For generations, researchers suspected that much more lay hidden beneath the surface, but suspicion alone could not confirm it.

The tattoos that were visible suggested patterns of nature and ethnic identity, often formed from clusters of small dots. Scholars believe these were made by repeatedly poking a single-pointed tool into the skin. The designs were usually placed on the hands and forearms, discreet locations that could be easily covered. Tattooing, at least in earlier periods, appeared to be primarily associated with women.

But this understanding, shaped by incomplete evidence, was about to change.

Seeing What the Eye Could Not

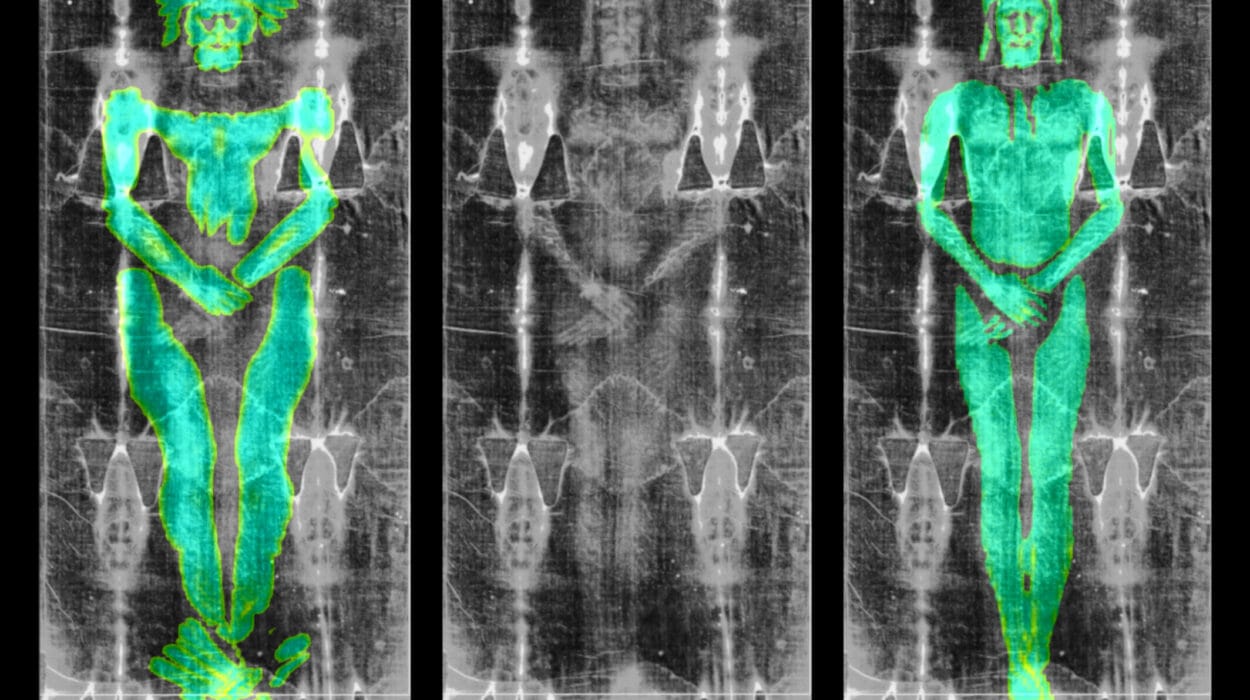

The turning point came not from the ground, but from light. Researchers turned to multispectral imaging, a technique capable of capturing images across multiple wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum. This method allows scientists to see details that ordinary vision cannot detect, especially on aged or mummified skin.

In a study published in PNAS, researchers applied multispectral imaging to human remains from three sites in Sudan: Semna South, Kulubnarti, and Qinifab School. The goal was simple but ambitious. They wanted to look again, more deeply, at skin that had already been studied, and ask what had been missed.

What they found was remarkable. The technology allowed tattoos to be examined at the microscopic level, revealing faded or previously invisible markings. Tattoos emerged on darkened skin, on aged remains, and on bodies where no markings had been recorded before.

In total, tattoos were identified on more than 27 individuals. Among them was an 18-month-old child with clearly defined tattoo marks. Even more striking was the discovery of possible tattooing on an infant aged between 7.5 and 10.5 months. These were not isolated anomalies. They were part of a broader pattern that reshaped how researchers understood tattooing in ancient Nubia.

A Shift Written on the Face

To understand why these tattoos appeared where they did, and on whom, researchers had to look beyond skin and ink, and into history itself.

Around the 7th century CE, Christianity spread across the Nubian region. With it came significant cultural changes, including shifts in tattooing practices. The survey examined 1,048 individuals, and the site of Kulubnarti, primarily occupied during the Christian era, revealed a striking transformation.

At Kulubnarti, 19% of individuals were tattooed. These tattoos were no longer confined mostly to women. Men, women, and toddlers all bore markings. Even more telling was where those markings appeared. Instead of being hidden on hands or forearms, tattoos were placed prominently on the face, often on the forehead, temples, and cheeks.

The face is impossible to ignore. A tattoo there is not private or subtle. It declares something openly, to everyone who looks. The shift from discreet to defining suggests a profound change in how tattoos functioned within Nubian society during this period.

The techniques themselves may have changed as well. Evidence suggests a move away from slow, dot-based hand-poking toward faster, single-puncture methods using sharper tools, resembling a knife point. This evolution may have made facial tattooing more practical, especially if it became more widespread.

Children at the Center of the Story

Perhaps the most emotionally powerful aspect of the discovery lies with the youngest individuals. Tattoos on infants and toddlers raise questions that echo across centuries. These markings were not chosen by the children themselves. They were placed with intention by the adults who cared for them.

The presence of facial tattoos on such young individuals suggests that these markings were not about personal achievement or individual storytelling in the modern sense. Instead, they likely reflected identity assigned at birth or early childhood. Religious belonging, community affiliation, or cultural protection may have been part of their meaning, though the study itself focuses on what can be seen and documented, rather than speculating beyond the evidence.

What is clear is that tattooing had become deeply embedded in social life. It reached across age, gender, and visibility, leaving its mark even on those who had lived less than a year.

Filling a Long-Standing Silence

Before this study, only 30 instances of tattoos had been recorded from the Nile Valley across a span of 4,000 years. That sparse record left enormous gaps in understanding how tattooing practices evolved and what they meant within different historical contexts.

By surveying more than a thousand individuals and applying advanced imaging techniques, researchers were able to dramatically expand that picture. The findings created crucial connections between tattooing in the medieval period and practices seen in more modern times in the Nile Valley.

What once appeared as isolated examples now forms a coherent pattern. Tattoos were not rare curiosities. They were a living tradition, shaped by religious change, technological adaptation, and social meaning.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research matters because it restores voices that history nearly erased. It shows how technology can reopen conversations with the past, allowing us to see people not just as skeletal remains, but as individuals who lived within rich cultural systems.

The discovery challenges assumptions about who was tattooed and why. It reveals that tattooing was not limited to adults or women, nor was it always hidden. It was, at times, a public and defining marker of identity, placed on the most visible part of the human body.

Most importantly, the research demonstrates how much of human history still lies hidden in plain sight. The past has not finished telling its story. Sometimes, it only needs new ways of looking to begin speaking again.

More information: Anne Austin et al, Revealing tattoo traditions in ancient Nubia through multispectral imaging, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2517291122