Every moment of being alive is stitched together from events that move at wildly different speeds. A blink happens in an instant. A sudden sound makes you flinch before you can think. Meaning, context, and understanding take longer, unfolding gradually as the brain gathers pieces and fits them together. This constant dance between the fast and the slow is something the human brain performs without pause, yet how it does so has remained a mystery hiding deep within its tangled wiring.

A new study from Rutgers Health, published in Nature Communications, steps into this mystery with a sense of quiet revelation. The research tells a story not of isolated brain regions acting alone, but of a vast network learning how to share time itself. It shows how the brain integrates signals that move at different speeds, weaving them together across white matter pathways to support cognition and behavior.

At the center of the study is a simple but profound idea: not all parts of the brain live in the same moment.

Regions That Live Fast and Regions That Linger

Different regions of the brain are tuned to different rhythms. Some areas are built to respond almost instantly, ideal for split-second reactions and immediate sensory input. Other regions operate over longer windows of time, allowing for reflection, context, and meaning to emerge. Scientists refer to this property as intrinsic neural timescales, or INTs.

These intrinsic timescales shape how each region processes information locally. But human behavior does not arise from isolated pockets of activity. It emerges from coordination, from information traveling across the brain’s complex web of white matter connectivity pathways. The question that has long hovered over neuroscience is how these fast and slow processes are brought together into something coherent.

According to Linden Parkes, assistant professor of Psychiatry at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School and the senior author of the study, this integration is essential to how we act in the world.

“To affect our environment through action, our brains must combine information processed over different timescales,” Parkes said. “The brain achieves this by leveraging its white matter connectivity to share information across regions, and this integration is crucial for human behavior.”

That sentence captures the heart of the study. Action, thought, and behavior are not simply about speed or slowness alone. They depend on the brain’s ability to coordinate across time.

Mapping the Highways of Thought

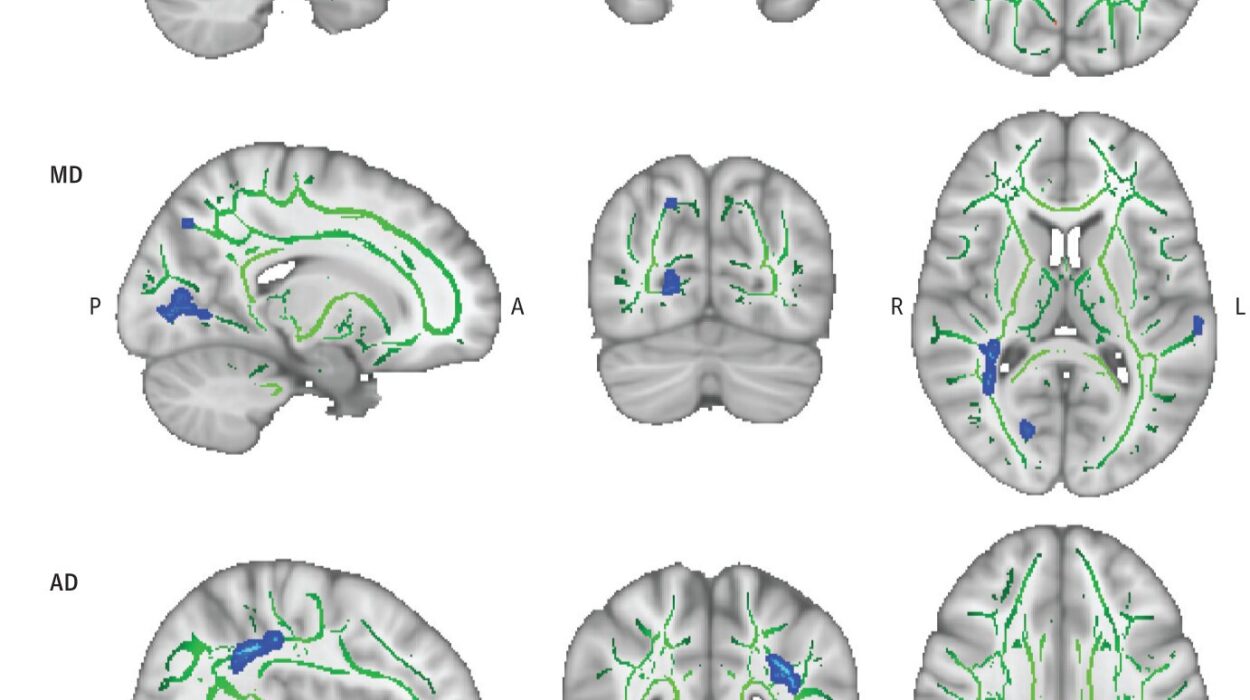

To explore how this coordination happens, Parkes and his team turned to an unusually rich dataset. They analyzed multimodal brain imaging data from 960 individuals, each one offering a detailed snapshot of how their brain is wired. From this data, the researchers built connectomes, intricate maps that show how different brain regions are connected through white matter pathways.

These maps are not static diagrams. They represent living systems through which information flows. To understand that flow, the team applied mathematical models designed to describe how complex systems change over time. This approach allowed them to examine how information moves across the network and how the timing properties of one region influence others.

“Our work probes the mechanisms underlying this process in humans by directly modeling regions’ INTs from their connectivity,” Parkes said. “This draws a direct link between how brain regions process information locally and how that processing is shared across the brain to produce behavior.”

In other words, the researchers did not treat intrinsic timescales as abstract traits. They modeled them as properties that emerge from connectivity itself. The brain’s wiring, the study suggests, does not merely transmit information. It shapes how time is experienced by different regions.

When Timing Shapes Thought

As the analysis unfolded, a striking pattern emerged. The distribution of neural timescales across the cortex played a crucial role in how efficiently the brain could switch between large-scale activity patterns related to behavior. This switching is not just a technical detail. It is fundamental to cognition, allowing the brain to move between different modes of processing as situations change.

What made the finding even more compelling was its variability. This organization of timescales was not identical across people. Instead, it varied from individual to individual.

“We found that differences in how the brain processes information at different speeds help explain why people vary in their cognitive abilities,” Parkes said.

This insight reframes individual differences in cognition in a subtle but powerful way. It suggests that variation in cognitive abilities may not only be about how much information the brain can process, but about how well its timing is coordinated. A brain that integrates fast and slow information more efficiently may be better equipped to handle complex tasks, adapt to new situations, and sustain flexible behavior.

Wiring That Matches the Mind

The study went further, grounding these timing patterns in biology. The researchers discovered that the observed distributions of intrinsic neural timescales are linked to genetic, molecular and cellular features of brain regions. This connection ties the abstract idea of information timing directly to the physical structure and biology of the brain.

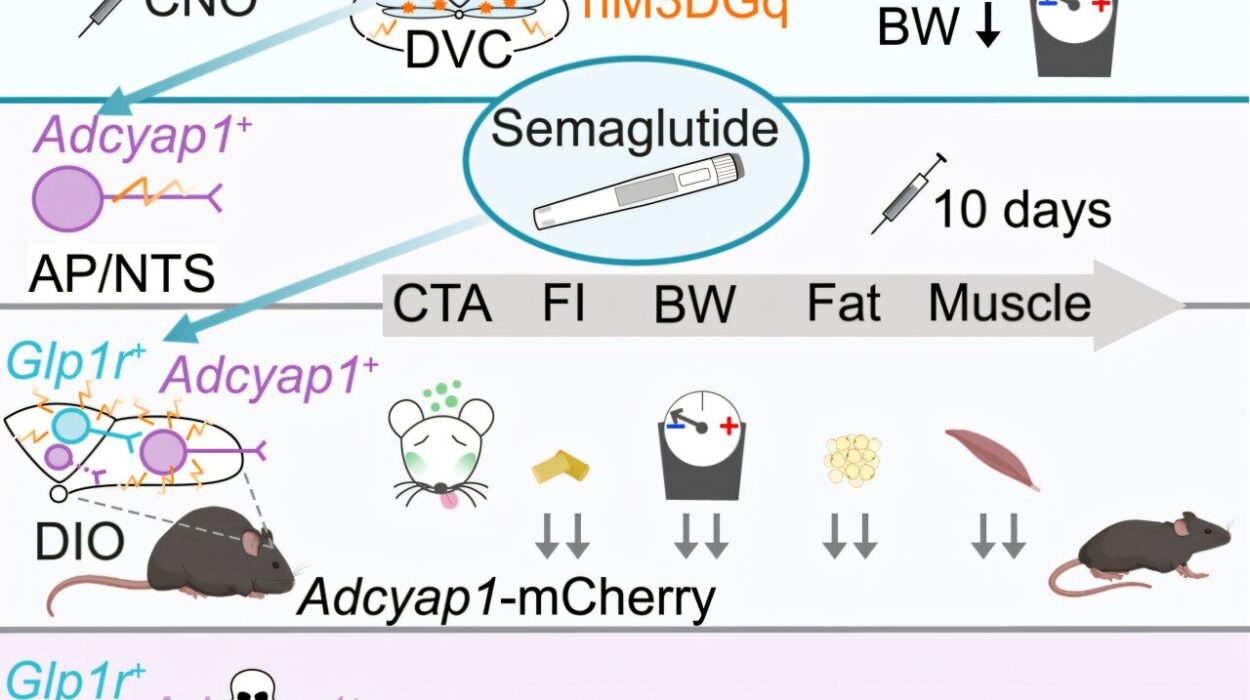

Even more strikingly, similar relationships were observed in the mouse brain. This suggests that the mechanisms uncovered by the study are conserved across species, hinting at a fundamental principle of brain organization rather than a quirk of human cognition.

“Our work highlights a fundamental link between the brain’s white-matter connectivity and its local computational properties,” Parkes said. “People whose brain wiring is better matched to the way different regions handle fast and slow information tend to show higher cognitive capacity.”

This finding paints brain wiring not as a fixed blueprint, but as a dynamic match between structure and function. The way regions are connected must align with how they process time. When that alignment is strong, cognition appears to benefit.

From Understanding to Possibility

The implications of this work do not stop at healthy cognition. Building on these findings, the research team is now extending the work to study neuropsychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression. The goal is to examine how disruptions in brain connectivity may alter information processing across timescales.

Although this next step is still unfolding, it points to a future where understanding the timing of brain activity could help explain the cognitive and behavioral challenges seen in these conditions. If connectivity shapes intrinsic neural timescales, then altered wiring could lead to mismatches in how fast and slow information is integrated.

The study itself was a collaborative effort, bringing together researchers across institutions. Alongside Parkes, the work involved Avram Holmes, an associate professor of psychiatry and a core member of the Rutgers Brain Health Institute and the Center for Advanced Human Brain Imaging Research, as well as postdoctoral researchers Ahmad Beyh and Amber Howell, and Jason Z. Kim from Cornell University. Their combined expertise helped turn a complex question into a coherent scientific narrative.

Why This Research Matters

This study matters because it reshapes how we think about the brain’s relationship with time. It shows that cognition is not simply about where activity happens, but about when it happens and how those moments are coordinated across the brain’s network.

By linking intrinsic neural timescales to white matter connectivity, the research provides a framework for understanding why people think and behave differently, even when their brains contain the same basic parts. It grounds those differences in measurable features of brain organization, tying behavior to biology without reducing it to a single cause.

Perhaps most importantly, the study offers a unifying perspective. Fast reactions and slow reflections are not competing processes. They are partners, brought together through the brain’s wiring to create coherent behavior. Understanding how that partnership works opens new doors for studying cognition, individuality, and mental health.

In revealing how the brain weaves together moments that move at different speeds, this research brings us closer to understanding not just how we think, but how we experience time itself.

More information: Jason Z. Kim et al, Inferring intrinsic neural timescales using optimal control theory, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-66542-w