Multiple sclerosis is not a sudden catastrophe. It is a slow, unsettling unraveling. Inside the brain, optic nerve, and spinal cord, the body’s own immune system begins to mistake protection for threat. It attacks myelin, the insulating sheath that allows nerve cells to send signals smoothly. As myelin erodes, the body falters. Vision blurs. Muscles weaken. Balance slips away. Coordination dissolves into uncertainty.

For people living with progressive multiple sclerosis, or P-MS, this decline does not come in dramatic waves. It creeps forward steadily, year after year. Symptoms begin quietly and worsen without remission. Scientists have spent decades trying to understand what drives this relentless progression, but the inner machinery of the disease has remained stubbornly opaque.

Now, a new study published in Nature Neuroscience offers a clearer picture of what may be happening inside the brain during progressive MS. Drawing on work by researchers at the University of Saskatchewan, the University of Montreal, the University of Calgary, and other institutions, the study tells a story of chemical damage, immune system misfires, and a delicate balance that slowly tips toward degeneration.

A Trail of Damage Left by Oxidative Stress

At the center of this research lies oxidative stress, a process that occurs when reactive oxygen molecules accumulate in excess and begin damaging cells. Oxidative stress is not foreign to biology; it is part of normal life. But in progressive MS, it appears to spiral out of control.

One result of oxidative stress is the creation of chemically altered molecules known as oxidized phosphatidylcholines, or OxPCs. These molecules are not passive debris. According to the researchers, they are actively harmful to nerve cells.

“Oxidized phosphatidylcholines (OxPCs) are neurotoxic byproducts of oxidative stress elevated in the central nervous system (CNS) during progressive multiple sclerosis (P-MS),” Ruoqi Yu, Brian M. Lozinski and their colleagues write in their paper. “How OxPCs contribute to the pathophysiology of P-MS is unclear.”

This uncertainty became the starting point for their investigation. Rather than observing the disease from a distance, the researchers decided to recreate part of its chemical environment and watch what unfolded.

Recreating Progressive MS Inside the Brain

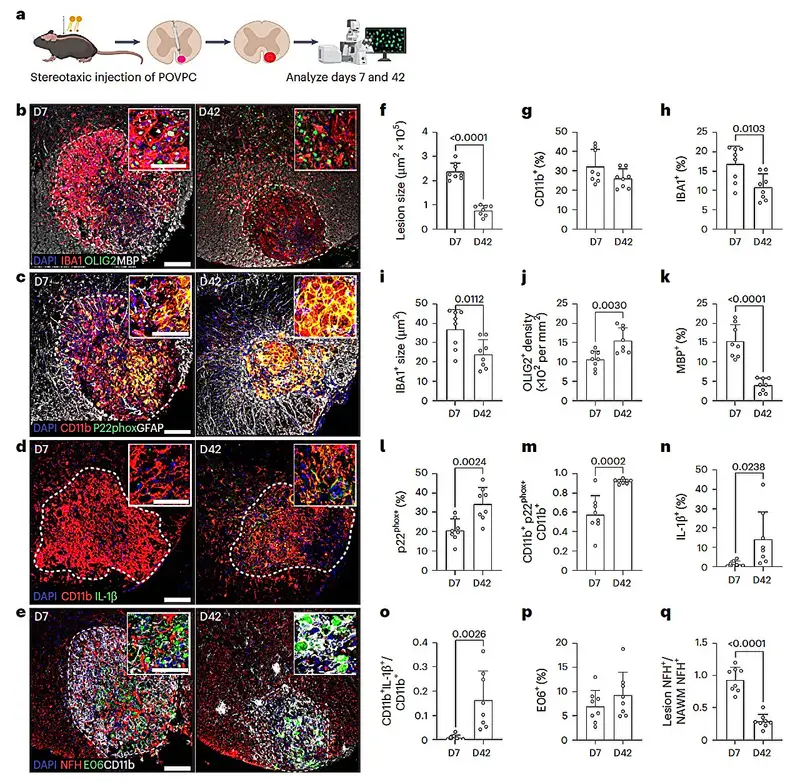

To explore the role of OxPCs, the team built a new mouse model of progressive MS. They introduced OxPCs directly into specific regions of the mice’s brains using stereotactic surgery, a precise technique that allows scientists to target exact locations within the central nervous system.

This was not a short-term experiment designed to trigger an immediate response. The goal was to observe what happens over time when these neurotoxic molecules settle into the brain and remain there.

“We show that stereotactic OxPC deposition in the CNS of mice induces a chronic compartmentalized lesion with pathological features similar to chronic active lesions found in P-MS,” wrote the authors.

What emerged was striking. The lesions that formed in the mice’s brains did not fade away. They persisted, evolving into chronic damage that closely mirrored what doctors see in people with progressive MS. The researchers were no longer looking at an abstract model; they were witnessing a living approximation of the disease’s slow-burning pathology.

The Brain’s Guardians and Their Gradual Replacement

Within the brain, immune defense is largely handled by microglia. These resident immune cells patrol neural tissue, responding to injury and infection while maintaining a fragile peace. In the early stages of OxPC exposure, microglia appeared to do their job. They worked to protect nerve cells and limit damage.

But this protection did not last.

As the OxPC lesions became chronic, the researchers noticed a shift. Microglia were gradually replaced by monocyte-derived macrophages, immune cells that originate in the blood rather than the brain. Unlike microglia, these incoming macrophages were associated with greater harm.

“Using this model, we found that although microglia protected the CNS from chronic neurodegeneration, they were also replaced by monocyte-derived macrophages in chronic OxPC lesions,” the authors explained.

This replacement marked a turning point. Instead of containment, damage accelerated. The immune system, once a defender, became an amplifier of destruction.

Aging Tips the Balance Toward Damage

Progressive MS is more likely to emerge later in life, and aging itself is a known risk factor. The researchers wanted to understand how age might influence the immune dynamics they were observing.

To do this, they compared younger and older mice exposed to OxPCs. The differences were clear and troubling. Aging altered the composition of microglia and weakened their protective role. In older mice, the shift toward damaging immune cells happened more readily, and the resulting neurodegeneration was more severe.

“Aging, a risk factor for P-MS, altered microglial composition and exacerbated neurodegeneration in chronic OxPC lesions,” the researchers wrote.

This finding helps explain why progressive MS often takes hold later in life. As the brain’s immune environment changes with age, its ability to contain chemical and inflammatory damage appears to falter.

Following the Signals That Fuel Inflammation

Oxidative stress and immune cell replacement were only part of the picture. The researchers also examined inflammatory signaling pathways that might be driving the damage forward.

They focused on enzymes known as Caspase-1 and Caspase-4, which play key roles in activating inflammatory signals. Some mice in the study lacked these enzymes entirely. In others, the researchers blocked a specific inflammatory pathway involving the IL-1 receptor.

The effects were dramatic. In both cases, nerve cell damage was significantly reduced. The chronic degeneration seen in untreated mice slowed, suggesting that inflammation was not merely a bystander but a central engine of disease progression.

“Amelioration of disease pathology in Casp1/Casp4-deficient mice and by blockade of IL-1R1 indicate that IL-1β signaling contributes to chronic OxPC accumulation and neurodegeneration,” writes Yu. Lozinski and their colleagues.

This result tied the story together. OxPCs, oxidative stress, immune cell changes, and inflammatory signals were not isolated factors. They formed a self-reinforcing loop, each element intensifying the others.

A Glimpse of New Therapeutic Possibilities

The study does not claim to offer a cure. But it does something just as important: it identifies specific drivers of damage that could potentially be targeted.

“These results highlight OxPCs and IL-1β as potential drivers of chronic neurodegeneration in MS and suggest that their neutralization could be effective for treating P-MS.”

By showing that blocking inflammatory signaling or preventing oxidative damage can reduce neurodegeneration in a model of progressive MS, the research opens doors to new treatment strategies. Future therapies might aim to neutralize OxPCs, dampen IL-1β signaling, or protect microglia from being displaced by more harmful immune cells.

Other research teams are likely to attempt to replicate and extend these findings, probing deeper into how oxidative stress and inflammation interact in the human brain.

Why This Research Matters

Progressive multiple sclerosis has long been one of the most difficult neurological diseases to understand and treat. Unlike relapsing forms of MS, it does not offer clear pauses or recoveries. Its damage accumulates quietly, often outpacing available therapies.

This study matters because it transforms that quiet mystery into a coherent narrative. It shows how chemical byproducts of oxidative stress can lodge themselves in the brain, how the immune system responds with both protection and harm, how aging weakens those defenses, and how inflammatory signals lock the process into a chronic cycle of degeneration.

By illuminating these mechanisms, the research provides something invaluable to patients and scientists alike: clarity. With clarity comes direction, and with direction comes the possibility of slowing a disease that has long seemed unstoppable.

In the story of progressive MS, this work does not write the final chapter. But it does turn a crucial page, revealing pathways that may one day be interrupted, softened, or healed.

More information: Ruoqi Yu et al, Oxidized phosphatidylcholines deposition drives chronic neurodegeneration in a mouse model of progressive multiple sclerosis via IL-1β signaling, Nature Neuroscience (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41593-025-02113-y.