Most people know the moment. Someone walks into a room and before they say a word, something feels off. Their eyes seem heavy. Their lips look pale. Their expression carries a tired stillness that words have not yet explained. Long before thermometers or medical tests, humans learned to read these silent signals. They mattered, because recognizing sickness in others could mean avoiding danger oneself.

A new study published in Evolution and Human Behavior takes that familiar human experience and places it under the careful lens of science. It asks a deceptively simple question: when illness leaves subtle traces on a person’s face, who notices them more accurately? The answer, according to the data, points gently but clearly toward women.

Faces That Were Not Acting

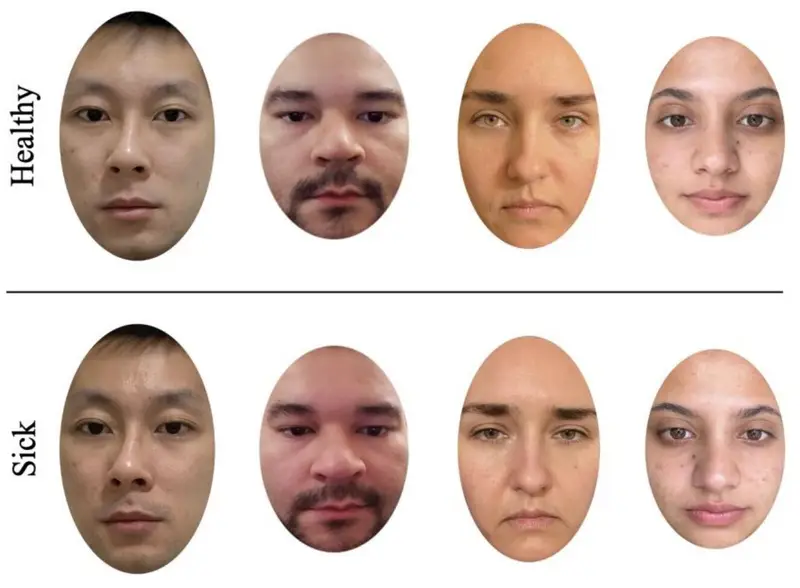

Past research has often tried to understand illness perception by showing people manipulated images or photographs of individuals whose sickness had been artificially induced. While those studies offered insights, they left an open question lingering in the background. Would people respond the same way to faces marked by real, naturally occurring illness rather than laboratory-made cues?

The researchers behind this new study wanted to find out. They focused on ordinary faces in ordinary conditions, capturing moments of genuine sickness and genuine health. Their goal was not to exaggerate illness but to see whether subtle, everyday signals were enough for observers to notice something was wrong.

To do this, they recruited 280 undergraduate students, evenly divided between men and women. Each participant was asked to rate 24 photographs. These images showed 12 individuals photographed twice: once while sick and once while healthy. The faces were cropped and stationary, offering no clues from posture, movement, or voice. All that remained was the face itself.

Judging More Than Just Health

The participants were not simply asked whether someone looked sick. Instead, they evaluated each face across six illness-related dimensions using 9-point Likert scales. These dimensions included safety, healthiness, approachability, alertness, social interest, and positivity. Through these ratings, the researchers could capture a fuller emotional and social response to illness cues.

A face that looked unhealthy might also seem less approachable. A tired expression might suggest low alertness or diminished social interest. Together, these perceptions form a broader sense of what the researchers describe as “lassitude,” a word that captures fatigue, low energy, and disengagement.

The study authors explain their approach clearly: “Given that these dimensions are positively correlated with each other and have been previously used to assess sick face sensitivity, we created a latent lassitude perception variable, indexed by the six dimensions that each tapped unique but related constructs. We also predicted that sex would predict latent lassitude perception, with females showing more accuracy in their ability to discriminate between sick and healthy faces than males.”

This was not a test of intuition alone. It was a structured attempt to understand whether one group consistently detected sickness more accurately across multiple emotional and social cues.

A Subtle but Consistent Difference

When the ratings were analyzed, the pattern became clear. Women, on average, were better at distinguishing sick faces from healthy ones. The difference was not dramatic. It did not suggest that men were unaware or incapable. But it was statistically significant and repeated across the study.

In practical terms, women tended to sense the quiet signs of illness more reliably. A slight droop in the eyelids, a faint dullness in expression, or a reduced sense of positivity registered more clearly in their evaluations. Across the six dimensions, their ratings aligned more closely with whether the person in the photo was actually sick or healthy.

The researchers emphasize that the difference was small. Yet in science, consistency matters. A modest effect that appears reliably across many observations suggests something deeper than chance.

Echoes from Human History

Why might such a difference exist? The study explores two major hypotheses, both rooted in human evolutionary history.

The first is known as the primary caretaker hypothesis. Throughout much of human history, women were more often responsible for caring for infants and young children. In this context, the ability to detect illness early would have been crucial. Babies cannot describe their symptoms. Young children may not recognize when something is wrong. Subtle changes in appearance or behavior could be the first warning sign.

According to this hypothesis, women who were better at recognizing these cues would have been more effective caregivers. Over generations, this ability may have been favored because it increased the chances of offspring survival.

The second explanation is called the contaminant avoidance hypothesis. This idea focuses not on caregiving, but on self-protection. It suggests that women experience higher levels of disgust than men, which may sharpen their sensitivity to signs of disease.

The study authors write, “These differences are theorized to result from repeated periods of immune suppression across the reproductive lifespan, occurring both during pregnancy and in the luteal phase of the monthly cycle, in anticipation of pregnancy. Females, therefore, overall, may have had greater selective pressure for disease-avoidance than males.”

In this view, detecting illness quickly is not just about caring for others, but about avoiding exposure oneself during vulnerable periods. Over time, this heightened awareness could become part of how faces are read and interpreted.

The Quiet Language of Lassitude

What makes this research particularly intriguing is how it highlights the quiet nature of illness perception. The faces in the study were not dramatic. There were no obvious rashes, no exaggerated expressions of pain. Instead, the cues were subtle, woven into the fine details of expression and vitality.

The concept of lassitude captures this subtlety. It is not simply looking sick. It is looking less engaged with the world, less alert, less socially open. These are the kinds of changes people often notice without consciously realizing why.

The study suggests that women may be slightly better attuned to this quiet language. Not because they are actively searching for illness, but because their perception integrates multiple small signals into a coherent impression.

The Boundaries of the Study

The researchers are careful to acknowledge the limits of their findings. All participants were undergraduate students, which means the results may not apply to all age groups or cultural backgrounds. Life experience, health awareness, and social roles could all influence how illness cues are perceived.

The study also focused only on faces. Real-life illness detection involves much more. Voice tone, posture, movement, and behavior all contribute to how sickness is perceived. The photos used were stationary and cropped, removing these additional layers of information.

The researchers note that these other indicators may influence sickness perception to a different degree. Future studies could explore how facial cues interact with voice or body language, and whether the observed sex difference remains consistent in more dynamic settings.

Why This Research Matters

At first glance, the idea that women are slightly better at noticing sick faces may seem like a small curiosity. But it touches on something fundamental about human social life.

Illness perception shapes how we interact with one another. It influences who we approach, who we avoid, and how we respond emotionally to others. These decisions often happen below conscious awareness, guided by impressions formed in a fraction of a second.

Understanding how different people perceive illness can help researchers better grasp the social dynamics of health and disease. It can shed light on caregiving behaviors, social avoidance, and even the emotional experience of being sick and seen by others.

More broadly, this research reminds us that faces carry stories we may not even realize we are reading. Tiny changes in expression can signal vulnerability, fatigue, or risk. And while everyone shares this ability to some degree, subtle differences in sensitivity may reflect deep-rooted patterns shaped by human history.

In a world still deeply affected by concerns about illness and contagion, understanding how we perceive sickness in others is more relevant than ever. This study does not claim to offer final answers. Instead, it opens a quiet window into the invisible conversations happening every time two people look at each other, where health, care, and caution are silently negotiated through the human face.

More information: Tiffany S. Leung et al, Individual differences in sick face sensitivity: females are more sensitive to lassitude facial expressions than males, Evolution and Human Behavior (2026). DOI: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2025.106803