Archaeology is often a dialogue with silence. The bones, stones, and remnants left behind by ancient cultures do not speak in words, yet they whisper stories of lives lived thousands of years ago. Among these fragments of the past, some discoveries challenge our expectations and unsettle our imaginations. One such discovery comes from the Neolithic Liangzhu culture of southern China, a society that thrived around 5,300–4,500 years ago.

In a recent study led by Dr. Sawada and colleagues, published in Scientific Reports, archaeologists uncovered 183 human bones from Liangzhu sites. Of these, 52 bore evidence of deliberate modification. These were not ordinary remains: they were worked human bones, reshaped and transformed by human hands. This discovery marks the first and only known instance of human bone modification in Neolithic China.

What might compel a culture to alter and repurpose the very bones of its people? The answer lies not only in the physical remains but also in the broader story of Liangzhu society, its urbanization, its rituals, and the shifting bonds between the living and the dead.

The Liangzhu Culture: An Early Urban Power

The Liangzhu culture represents one of the earliest complex societies in East Asia. Emerging in the fertile Yangzi River Delta, Liangzhu people built vast walled settlements, encircled by moats and strengthened with dams and canals. Their achievements in hydrological engineering were extraordinary, transforming wetlands into organized landscapes that supported urban life.

At the heart of these settlements were palaces, altars, and workshops, evidence of social hierarchy and centralized leadership. Cemeteries, too, reveal that Liangzhu society was not egalitarian but stratified, with elites commanding resources and labor. Jade artifacts, intricately carved and ritually significant, speak of religious or cosmological systems now lost to us.

Yet unlike later dynasties that would leave written records, Liangzhu remains mute in text. Without words to guide interpretation, archaeologists must rely on material culture—the architecture, the artifacts, and, in this case, the human bones.

The Puzzle of the Worked Bones

The bones uncovered by Dr. Sawada’s team were not randomly scattered. Many were found in canals and moats, deliberately discarded in watery boundaries of the city. This context itself is striking: in many cultures, waterways serve as liminal spaces, thresholds between life and death, the sacred and the mundane.

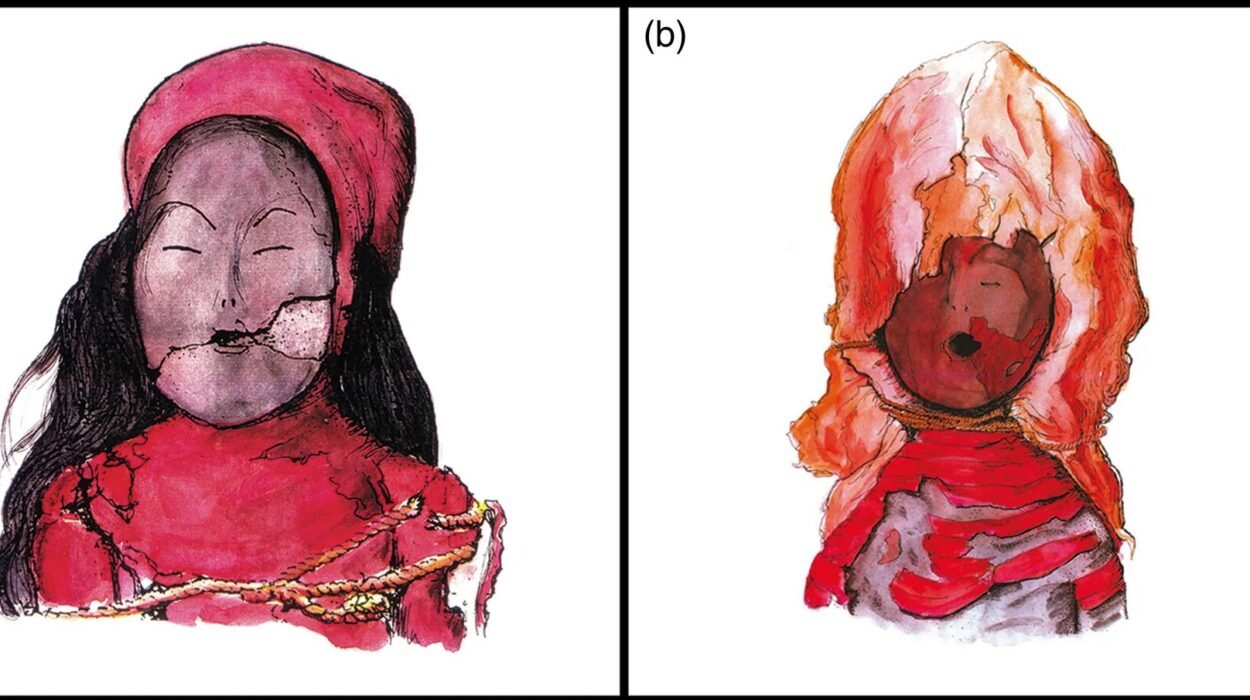

The modifications were varied but deliberate. Some bones had been transformed into skull cups, their upper crania reshaped into vessels. Others resembled masks, with facial skulls carefully prepared. Still others were small, plate-like fragments or mandibles shaped for unknown purposes. Limb bones bore traces of working, their surfaces flattened or altered.

Importantly, the bones did not belong to a single category of individuals. Adults, adolescents, and even children were represented. Both men and women underwent this transformation. There was no apparent preference for age or sex. Instead, what they shared were signs of nutritional stress, suggesting many of these individuals came from lower social classes.

Violence, Kinship, or Ritual?

When archaeologists encounter worked human bones, the first interpretation often involves violence—trophies of war, marks of enmity, or evidence of ritualized cannibalism. Yet the Liangzhu bones resist this narrative. They show no signs of dismemberment, no cut marks of butchery, no trauma suggesting violent conflict.

Instead, the evidence points to a different process. The lack of cutting marks indicates that the bones were not harvested immediately after death but collected after decomposition. Flesh had given way to bone before modification began. The majority of bones, around 80%, appear unfinished, never completed into functional objects.

This pattern suggests that these bones were not sacred relics of honored ancestors nor violent trophies of conquest. Rather, they may have been materials processed in workshops, treated almost as resources rather than revered remains.

The Transformation of Social Bonds

To understand this unusual practice, it helps to look at the broader social context. In earlier Neolithic societies, smaller and tighter-knit communities often buried their dead in formal graves, preserving kinship ties through commemoration. The dead were remembered as ancestors, their bones infused with meaning and continuity.

But Liangzhu was different. It was vast, urban, stratified. Kinship may have loosened in the face of anonymous city life. In such a society, not all individuals may have been afforded the dignity of ancestorhood. Some were remembered; others, perhaps, were not.

Dr. Sawada and his colleagues suggest that urbanization itself may have shifted attitudes toward death. In an impersonal society, bones of those outside immediate kinship networks may have been treated as “other”—neither enemies nor ancestors, but expendable. The act of working bones and discarding them unfinished into canals might reflect this transformation.

Water, Boundaries, and Ritual Disposal

The placement of bones in canals and moats carries symbolic weight. Water has often been seen as a boundary between worlds, a purifying or transitional space. To consign bones to the waters surrounding Liangzhu settlements may have been a way of marking their difference, removing them from the sphere of kinship and ancestor worship.

This is not unlike later practices in parts of China, where skull burials or alternative mortuary treatments developed. Though the specific meaning of Liangzhu’s bone-working remains unclear, it is consistent with societies experimenting with new forms of ritual and social organization during times of transition.

Unfinished Lives, Unfinished Bones

One of the most haunting aspects of this discovery is that most of the bones appear unfinished. They were not carefully crafted into permanent objects but abandoned mid-process. Why? Were they practice pieces, raw material that proved unsuitable, or ritual gestures never intended to be completed?

The high proportion of unfinished bones suggests they were neither rare nor sacred. Instead, they may have been plentiful, worked as part of a standardized process in workshops such as Zhongjiagang, then deliberately discarded. In this interpretation, death itself had become anonymous, its material remains stripped of individuality.

The Human Story Behind the Bones

While the archaeological evidence tells us about processes and patterns, it is the human dimension that lingers. Each of these bones belonged to a person, someone who lived, breathed, and struggled in the bustling world of Liangzhu. Many bore signs of poor nutrition, lives lived in hardship. Their transformation into unfinished artifacts may reflect not only the impersonal nature of urban society but also the inequality embedded within it.

These individuals were not the jade-bearing elites interred with ceremony. They were the marginalized, the forgotten, whose remains were treated not as symbols of reverence but as raw matter. In this sense, the worked bones may reveal the underside of Liangzhu’s brilliance: a society advanced in engineering and urban planning, yet one in which social bonds fractured under the weight of inequality.

The Significance of the Discovery

The worked bones of Liangzhu remain unique in Neolithic China. They stand apart from earlier traditions of burial and ancestor worship, and they do not continue into later practices of skull burial. They are, in this sense, a cultural anomaly, a singular experiment in how a society grappled with the meaning of death and the body.

For archaeologists, this discovery opens questions not only about Liangzhu but about the relationship between urbanization and mortuary practice. How do large, stratified societies change the way people view kinship, memory, and the dead? What do the choices of treatment—burial, commemoration, transformation, or disposal—reveal about social values?

Echoes Across Time

Though separated from us by five millennia, the Liangzhu worked bones resonate with timeless questions. How do we honor the dead? How do societies decide who is remembered and who is forgotten? What does it mean when human remains are treated as material rather than memory?

These questions remain as urgent today as in the Neolithic. In remembering the worked bones of Liangzhu, we confront both the ingenuity and the disquiet of human history—the ways in which progress and alienation can coexist, and how even in advanced societies, some lives are rendered invisible.

Conclusion: The Bones That Speak Without Words

The Liangzhu culture has no written records, no chronicles of kings or priests, no poems to explain its beliefs. Yet the bones, worked and unfinished, discarded into water, speak in their own way. They tell of a society negotiating the challenges of urbanization, inequality, and changing relationships between the living and the dead.

For us today, these bones are reminders of the fragility of human bonds and the ways culture shapes our deepest rituals. They show that even without words, the dead continue to shape the living—forcing us to reflect on what it means to remember, to forget, and to belong.

The canals of Liangzhu may have swallowed the bones, but they did not silence them. Thousands of years later, they still have a story to tell.

More information: Sawada et al, Worked human bones and the rise of urban society in the neolithic Liangzhu culture, East Asia, Scientific Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-15673-7