When we think of the foundations of civilization, images of monumental architecture, flourishing trade routes, or the first written symbols often come to mind. Yet, behind every great society lies something even more enduring: rules that bind people together, resolve disputes, and establish order. Among the earliest and most influential of these was Hammurabi’s Code, a remarkable collection of laws carved into stone nearly four thousand years ago. It was not merely a set of regulations but a declaration of justice, a proclamation of authority, and a window into the lives of an ancient people whose concerns, in many ways, echo our own.

Hammurabi’s Code is often described as the first written legal code in history. While other societies before Babylon had laws and customs, Hammurabi’s achievement was unique in that he recorded his laws publicly, in writing, so that all might see. It marked a turning point in human history, transforming justice from something oral and arbitrary into something concrete and enduring. These laws shaped the daily lives of Mesopotamians and influenced legal traditions for millennia, leaving a legacy still felt in the principles of modern justice today.

The World of Hammurabi

To understand Hammurabi’s Code, we must first step into the world of its creator. Hammurabi was the sixth king of the First Babylonian Dynasty, ruling from about 1792 to 1750 BCE in Mesopotamia, the fertile land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. This region, often called the “cradle of civilization,” had already seen the rise of Sumer, Akkad, and other early kingdoms. By Hammurabi’s time, Babylon was emerging as a powerful city-state, strategically located for trade and military expansion.

Hammurabi was not merely a conqueror—though he expanded his empire significantly through warfare and diplomacy—he was also a visionary statesman. His reign was marked by efforts to unify his diverse realm under a common framework of justice. Babylon was home to farmers, merchants, artisans, priests, slaves, and nobles, all living under the same sky but with different needs, disputes, and expectations. For Hammurabi, the creation of a universal legal system was both a political necessity and a profound expression of kingship.

In ancient Mesopotamian culture, kings were seen as chosen by the gods, guardians of order and justice. Hammurabi framed his code as divinely inspired, presenting himself as the shepherd of his people. By inscribing his laws into stone, he offered not only legal clarity but also a divine guarantee of fairness. His Code became a symbol of the sacred bond between ruler, people, and the gods who watched over them.

The Discovery of the Code

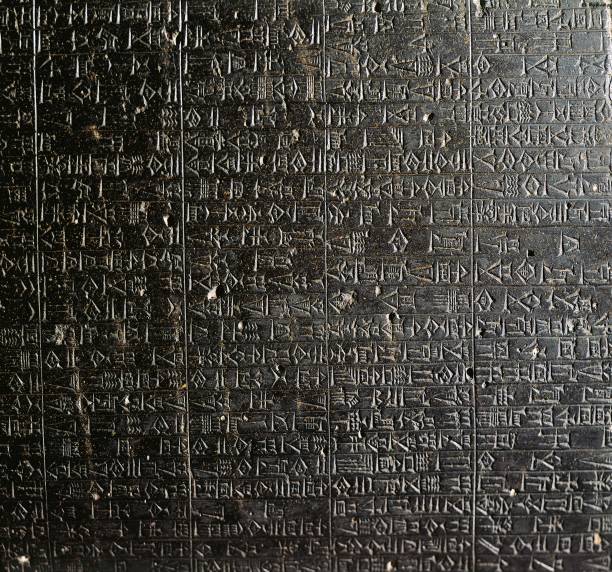

For centuries after Hammurabi’s death, his laws faded from memory, buried beneath the sands of Mesopotamia. It was not until the early 20th century that archaeologists rediscovered his monumental contribution. In 1901, French archaeologists working in Susa (modern-day Iran) unearthed a massive basalt stele inscribed with cuneiform writing. This was the famous Hammurabi’s Code, transported there as a war trophy by a later king.

Standing over seven feet tall, the black stone stele is crowned with an image of Hammurabi receiving authority from Shamash, the sun god and god of justice. Below the carving, etched into the stone in meticulous Akkadian script, are nearly 300 laws covering every aspect of Babylonian life. Today, this extraordinary artifact resides in the Louvre Museum in Paris, a silent witness to humanity’s first great experiment with written law.

The discovery of Hammurabi’s Code was a revelation for historians and the wider public alike. It not only shed light on Babylonian society but also demonstrated that the principles of justice, fairness, and governance were as old as civilization itself.

The Structure of the Code

Hammurabi’s Code is composed of a prologue, the body of laws, and an epilogue. The prologue sets the tone, presenting Hammurabi as a righteous king chosen by the gods to bring justice and protect the weak. It emphasizes that his authority comes from the divine, making his laws not just political but sacred.

The laws themselves, 282 in total (though some sections are damaged or missing), cover a wide range of topics: family matters, property disputes, trade, labor, agriculture, theft, assault, and more. They are written in conditional “if…then” statements, a style that lends them clarity and directness. For example, “If a man puts out the eye of another man, his eye shall be put out.” This style of law, known as casuistic law, remains recognizable in legal systems today.

The epilogue reaffirms Hammurabi’s role as protector of justice, calling upon future kings to uphold his laws and warning of divine punishment for those who might ignore or alter them. The structure itself reveals a society deeply concerned with order, fairness, and continuity.

Justice in the Ancient World

One of the most famous principles associated with Hammurabi’s Code is the idea of lex talionis, or the law of retaliation: “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.” This phrase has often been misunderstood. While it may sound harsh to modern ears, in its time it was a progressive step toward limiting revenge. Instead of endless cycles of blood feuds, the law established proportional justice. Punishments were meant to fit the crime, preventing excessive retaliation.

Yet Hammurabi’s justice was not blind. The Code clearly reflects the hierarchical nature of Babylonian society. Punishments varied depending on the social status of the offender and the victim. A noble striking another noble might face one penalty, while striking a slave could result in a much lighter punishment. Similarly, the value of property, marriage contracts, and inheritance rights all depended on class and gender.

This stratification reveals both the fairness and limitations of Hammurabi’s justice. On the one hand, it recognized that even the weakest members of society—slaves, widows, orphans—deserved some measure of protection. On the other hand, it enshrined inequality as part of the legal order. The Code, therefore, is a reflection of its time: a society striving for fairness within the boundaries of rigid social hierarchies.

The Role of Family and Property

Many of Hammurabi’s laws deal with family matters, underscoring the importance of kinship in Babylonian society. Marriage was not only a personal relationship but also an economic and legal contract. The Code addressed issues of dowries, inheritance, adultery, divorce, and legitimacy, ensuring that property and lineage were protected.

For example, if a man divorced his wife without cause, he was required to return her dowry. If a wife was unfaithful, however, the punishment could be severe, including death. These laws reveal both the value placed on family stability and the patriarchal norms that governed relationships.

Property rights were equally significant. Babylonian society was agrarian, dependent on land and agriculture. The Code includes detailed provisions on irrigation, crop damage, livestock, and tenancy agreements. It also regulated trade, debt, and wages, reflecting a society deeply engaged in commerce. By addressing these practical concerns, Hammurabi’s laws provided a framework for economic stability in a complex and growing kingdom.

Crime and Punishment

The severity of Hammurabi’s punishments has often been a subject of debate. Some penalties seem harsh, such as the death penalty for theft, false accusation, or adultery. Others were surprisingly pragmatic, such as fines for negligent farming practices or compensation for injuries.

One striking aspect of the Code is its attention to professional accountability. Builders, for example, were held to strict standards: if a house collapsed and killed its occupants, the builder could be put to death. This may sound brutal, but it established a clear sense of responsibility, ensuring that those providing services could not escape consequences for negligence.

Punishments were also symbolic, reinforcing the principle that crime had social consequences. By publicly declaring penalties, Hammurabi made justice not a private matter but a collective one. The laws thus served both as deterrents and as moral lessons for society.

The Religious Dimension

Religion permeated every aspect of Mesopotamian life, and Hammurabi’s Code was no exception. By presenting his laws as divinely ordained, Hammurabi linked human justice with cosmic order. Shamash, the god of the sun and justice, was depicted on the stele as handing Hammurabi a rod and ring, symbols of authority.

This divine framing gave the laws extraordinary legitimacy. To obey Hammurabi’s Code was not only to respect the king but also to honor the gods. Conversely, to break the law was not merely a crime against society but a sin against the divine order. This fusion of religion and law reinforced Hammurabi’s authority while instilling a sense of sacred duty in his subjects.

The Legacy of Hammurabi’s Code

Though carved in stone nearly four millennia ago, Hammurabi’s Code left a profound legacy. It influenced later legal systems in the ancient Near East, including those of the Hittites, Assyrians, and Israelites. Many biblical laws in the Old Testament bear striking similarities to Hammurabi’s provisions, suggesting that his Code helped shape the legal and moral traditions of Western civilization.

Beyond its historical influence, Hammurabi’s Code represents a milestone in the evolution of justice. It introduced the idea that laws should be public, written, and binding for all. It established the principle of proportional punishment, limiting personal vengeance. And it acknowledged the responsibility of rulers to protect the vulnerable and uphold fairness.

Even today, the Code resonates with modern debates about justice, inequality, accountability, and the rule of law. While we may not adopt Hammurabi’s punishments, the ideals of order, fairness, and transparency remain at the heart of legal systems worldwide.

A Mirror of Humanity

Hammurabi’s Code is more than a historical artifact—it is a mirror reflecting humanity’s timeless struggle to live together in fairness. It shows us the aspirations and contradictions of a society both advanced and imperfect. It reveals how deeply people of the past cared about justice, responsibility, and community.

At its core, Hammurabi’s Code tells us that the rule of law is one of humanity’s greatest achievements. It is the recognition that no society can endure without rules, that fairness must be sought even in the face of inequality, and that justice is both a human need and a divine calling.

The black stone stele in the Louvre may stand silent, but its words still speak. They remind us that the pursuit of justice is as old as civilization itself, and that while laws may change, the human desire for fairness, protection, and order remains constant.

Conclusion: The Enduring Voice of Stone

In the bustling heart of ancient Babylon, Hammurabi had his laws carved into stone so that none could claim ignorance and none could escape accountability. He knew that words alone were fleeting, but stone endures. And endure it has, carrying his vision of justice across centuries and civilizations.

Hammurabi’s Code was not perfect—it reflected the inequalities and harshness of its age. Yet it was a bold step toward a world where justice was written, accessible, and shared by all. It transformed law from a whispered custom into a public institution, and in doing so, it laid the foundation for legal systems that govern societies to this day.

To read Hammurabi’s Code is to travel back in time, to hear the voice of a king who sought to weave fairness into the fabric of society, and to recognize in his ancient words the enduring human quest for justice. It is a testament to our shared history, a reminder of how far we have come, and an invitation to reflect on how far we still have to go.