Today, we live in a world where information travels at lightning speed. A single tweet can topple reputations, spark movements, or spread misinformation to millions within hours. The internet has made virality part of daily life, so much so that we rarely stop to think about the mechanics behind it. We simply know that ideas can behave like living organisms, multiplying across screens, reshaping societies, and sometimes leaving devastation in their wake.

Yet this phenomenon is not unique to the digital age. Long before hashtags and social media algorithms, societies were shaken by waves of information spreading at epidemic speed. The “Great Fear” of 1789 in France stands as one of history’s clearest examples, where rumors, much like contagious pathogens, leapt from village to village and reshaped the course of a nation.

A Summer of Panic

The summer of 1789 was already tense in France. Inequality was deep, the monarchy faced unrest, and hunger stalked the countryside. When rumors spread that aristocrats were plotting to starve the peasants—burning fields, hoarding grain, and conspiring against the people—the fragile balance snapped.

Between July 20 and August 6, whispers ignited like wildfire. Villagers armed themselves, riots erupted, and the collective fear of conspiracy transformed into chaos. Though no aristocratic plot existed, the rumor took on a life of its own. Within two weeks, the panic—what historians later called la Grande Peur, or the Great Fear—had spread across much of rural France, fueling the French Revolution and hastening the collapse of feudalism.

Historians have long debated how the Great Fear could have moved so fast across such vast distances. But now, modern science has provided an unexpected answer: the spread of these rumors mirrors the spread of disease.

Modeling Rumors Like Epidemics

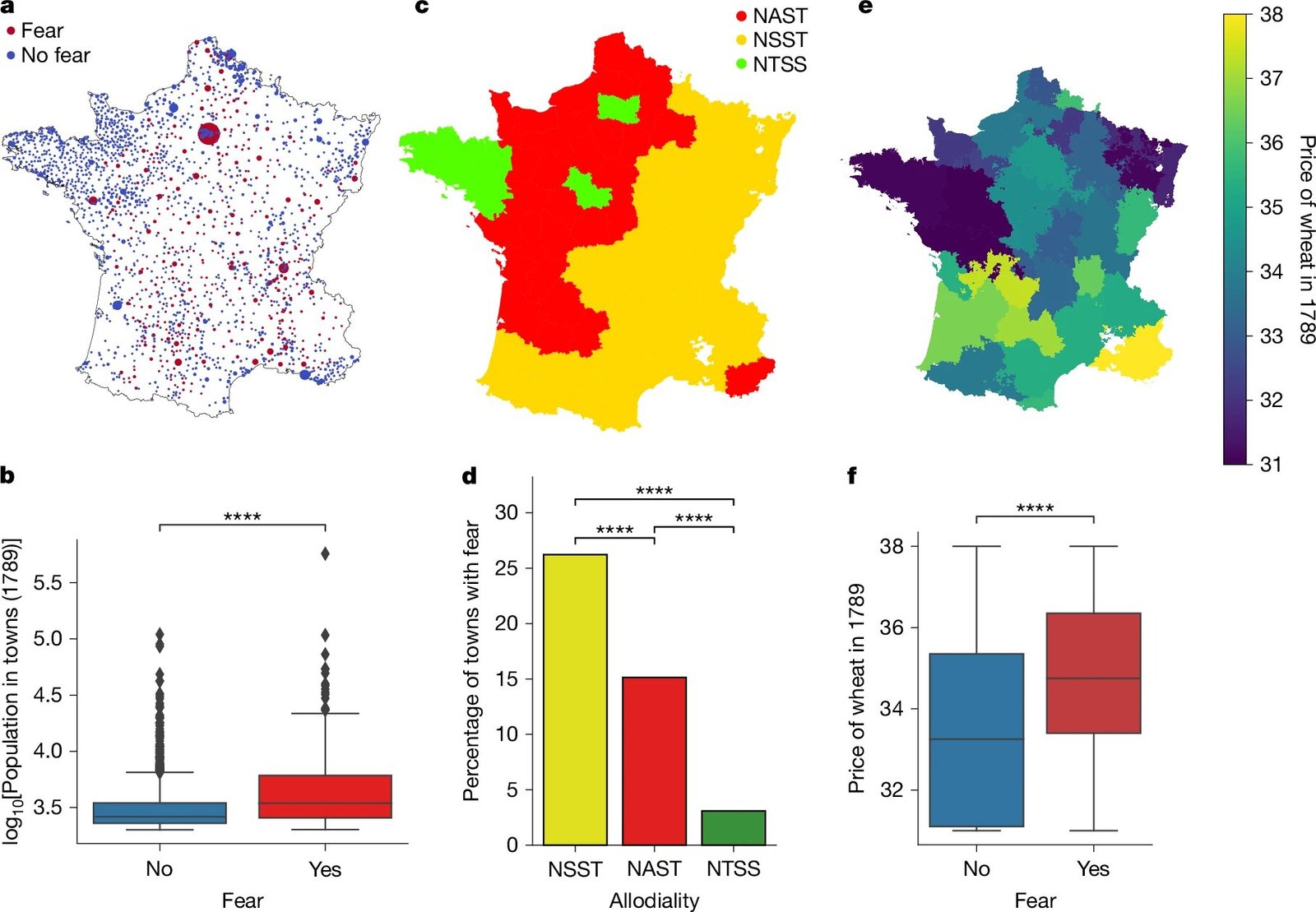

In a recent study published in Nature, researchers approached the Great Fear not simply as a historical episode but as a kind of outbreak. Using methods normally reserved for epidemiology—the study of how diseases spread—they digitized historical records to trace how the rumors traveled through towns, villages, and roads in 1789.

The results were startling. The researchers found that the spread of rumors during the Great Fear followed the same patterns as an infectious disease. They calculated the basic reproduction number, or R₀—a key parameter in epidemiology that measures how many others one infected individual is likely to pass the disease on to in a fully susceptible population. For the Great Fear, the R₀ was about 1.5.

In other words, on average, each “infected” person passed the rumor to one or two others. The outbreak peaked on July 30, before sharply declining, a trajectory strikingly similar to that of many viral epidemics.

Why Some Places “Caught” the Rumor Faster

Just as some communities are more vulnerable to outbreaks of disease, the study found that certain towns were more susceptible to the spread of rumor. Population size, wealth, literacy rates, and economic pressures like high wheat prices all played a role. Places where land ownership was concentrated and inequality ran high were particularly fertile ground for the fear to take hold.

The geography of rumor spread also revealed striking patterns. Transmission often followed major roads and postal routes—the 18th-century equivalents of today’s social media feeds. Instead of retweets and shares, information traveled by word of mouth, letters, and the movement of people along well-established routes. The spread happened in distinct waves, rolling across regions in a manner eerily similar to contagion maps used for diseases like influenza or COVID-19.

As one of the study’s authors noted, this is a general property of infectious diseases: large, well-connected hubs act as accelerators of transmission. In the 18th century, these hubs were prosperous towns. Today, they are digital platforms.

Fear, Rationality, and Politics

The Great Fear has often been painted as an emotional outburst—a case of collective panic untethered from reason. But the new study complicates this narrative. By applying epidemiological modeling, the researchers suggest that the spread of fear was not random chaos but a rational response to local conditions.

In villages where economic exploitation was stark, where laws reinforced feudal hierarchies, and where food insecurity loomed, the rumor of aristocratic conspiracy felt plausible. People believed it because their lived reality made it believable. The fear was not born in a vacuum; it was rooted in social and political tension, and the rumor simply provided a spark that set it ablaze.

This understanding reframes the Great Fear not as mass hysteria but as a politically charged moment, shaped by the structural realities of rural France.

Echoes in the Modern Age

If all of this feels strangely familiar, it should. The parallels to our own time are hard to ignore. The COVID-19 pandemic showed the world how quickly a biological virus can spread. Simultaneously, the pandemic revealed how misinformation—about masks, vaccines, or the origins of the virus—spread just as rapidly, often with consequences just as dangerous.

The Great Fear of 1789 shows us that viral rumors are not new. What has changed are the tools of transmission. Instead of roads and postal routes, we now have smartphones, social media platforms, and algorithms designed to maximize engagement. Instead of days or weeks, rumors can now leap continents in seconds.

But the underlying mechanics remain strikingly similar. Populations that feel vulnerable—whether economically, politically, or socially—are more likely to embrace misinformation. Well-connected hubs (whether bustling French market towns or modern Twitter feeds) accelerate the spread. And just like with disease, containment requires both understanding the vectors of spread and addressing the underlying vulnerabilities that make societies susceptible.

Lessons for Today

The Great Fear offers a powerful lesson: misinformation does not spread in a vacuum. It finds fertile ground where fear, inequality, and uncertainty already exist. Understanding this can help us prepare for the “outbreaks” of misinformation we face today.

Epidemiological models, once confined to the realm of viruses and bacteria, are now tools we can use to understand the dynamics of human communication. By mapping the spread of rumors, by calculating their reproduction numbers, and by identifying social “risk factors,” we can begin to predict and perhaps even curb the virality of false information.

This is not about silencing voices or suppressing ideas. It is about equipping societies with the awareness to distinguish between signal and noise, to recognize when fear is being exploited, and to respond not with panic but with reason.

The Viruses We Cannot See

When we think of contagion, we often think of coughs, fevers, and microbes invisible to the naked eye. But there is another kind of contagion—one woven from words, fears, and beliefs. These are the viruses of the mind, and they can be just as powerful as the viruses of the body.

The Great Fear of 1789 reminds us that ideas are not static. They live, move, and evolve. They can topple regimes, ignite revolutions, or destabilize communities. And just like diseases, they can be studied, mapped, and perhaps even prevented from doing their worst harm.

In the end, the story of the Great Fear is not just a historical curiosity. It is a mirror held up to our own time, reflecting both the fragility and resilience of societies in the face of uncertainty. As long as humans share stories, fears, and hopes, ideas will continue to spread like viruses. Our task is to learn how to live with this reality—and to shape it toward truth, rather than despair.

More information: Stefano Zapperi et al, Epidemiology models explain rumour spreading during France’s Great Fear of 1789, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09392-2