For more than a century, a mystery lay buried beneath the quiet soil of Margaret Island in Budapest. In the shadow of the ruins of a medieval monastery, archaeologists once unearthed the broken bones of a young man whose life and death were wrapped in royal intrigue and violence. The year was 1915, and the clues seemed to whisper the name of a lost Hungarian prince — Béla, Duke of Macsó.

Now, after more than a hundred years, an international team led by Hungarian researchers has finally solved this riddle. Through the combined power of archaeology, genetics, and forensic science, they have identified the remains of Duke Béla of Macsó — a descendant of two great royal houses, the Árpáds of Hungary and the Ruriks of Kievan Rus’. Their work, recently published in Forensic Science International: Genetics, does more than confirm a name; it breathes life into a story of power, betrayal, and human fragility buried beneath centuries of dust.

A Prince Between Two Dynasties

Béla of Macsó lived in the turbulent 13th century, a time when kingdoms were built and shattered by alliances and wars. He was born after 1243 to a family that bridged East and West. On his mother’s side, he was the grandson of King Béla IV of Hungary, a ruler remembered for rebuilding his kingdom after the devastating Mongol invasion. On his father’s side, Béla inherited the blood of the Rurik dynasty — the Scandinavian-descended princes who had ruled the powerful Kievan Rus’ for generations.

To be of both Árpád and Rurik descent was to stand at the crossroads of European history. Béla’s lineage connected him to the great Christian dynasties of medieval Europe and to the Byzantine Empire itself through his grandmother, Maria Laskarina, a member of the imperial Laskaris family. Yet this noble birth also placed him in the heart of political storms that would end his life violently and far too soon.

The Murder of a Duke

According to 13th-century chronicles, Béla’s life ended abruptly and brutally in November 1272. He was assassinated by Ban Henrik Kőszegi and his followers — powerful nobles of the Héder family — during one of Hungary’s many internal power struggles. Béla was still in his early twenties, a young man with influence, ambition, and royal blood. His death was not a random act of violence but a calculated strike within the treacherous world of medieval politics.

Contemporary accounts describe the murder in horrifying detail. His mutilated body was said to have been collected by his sister, Saint Margaret of Hungary, and his niece Erzsébet, who buried him in the Dominican monastery on Margaret Island. The burial site became a silent witness to one of medieval Hungary’s most tragic political crimes.

The Forgotten Bones

When archaeologists uncovered human remains in 1915 in the sacristy of the Dominican monastery, all evidence pointed to Béla of Macsó. The skeleton bore the marks of violent death: sword cuts, crushed bones, and shattered features. The anthropologist Lajos Bartucz analyzed the bones and counted 23 separate sword wounds, concluding that the young man had been attacked by multiple assailants from several directions — a brutal execution rather than a duel.

Then, the trail went cold. The skull was photographed and published by Bartucz in 1938, but afterward, the remains vanished from public knowledge. For decades, historians believed the bones had been lost amid the chaos of the Second World War. The Duke of Macsó faded once again into legend — a victim of time as much as violence.

Rediscovery and the Call of Science

The story took an extraordinary turn in 2018. In the vast anthropological collection of the Hungarian Museum of Natural History, curators stumbled upon a wooden box containing postcranial bones — the bones of the body — labeled in an old hand. Astonishingly, the skull had survived too, preserved in the Aurél Török Collection at Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE).

What had once been a ghost of history could finally be studied anew. Under the leadership of Dr. Tamás Hajdu of ELTE’s Department of Biological Anthropology, an international research team formed to reexamine the remains. The project brought together experts from ELTE’s Institute of Archaeogenomics, Harvard University, the Universities of Vienna, Bologna, and Helsinki, and several Hungarian institutions. It was an alliance of the humanities and the natural sciences — historians, anthropologists, geneticists, and forensic specialists united in pursuit of truth.

Their goal was both ambitious and deeply human: to give Béla of Macsó his identity back, to reconstruct his life and death, and to place his story within the broader narrative of medieval Europe.

The Science of a Prince

The analysis of the bones began with radiocarbon dating, a method that measures the decay of carbon isotopes to determine age. Curiously, the initial results suggested an earlier date than expected. The mystery was soon solved when isotope experts at the Institute for Nuclear Research in Debrecen discovered that Béla’s diet had distorted the readings.

Like many medieval nobles observing religious fasting, Béla likely consumed large amounts of fish and other aquatic animals. Because these animals fed on ancient carbon sources, they left a “reservoir effect” in the bones, making him appear older in radiocarbon years. It was a fascinating glimpse into the daily life of the young duke — his meals shaped by both faith and privilege.

Microscopic analysis of his dental calculus, or tartar, revealed more details of his diet. Trapped within the hardened plaque were over a thousand microfossils, including starch grains from wheat and barley. The grains bore the marks of cooking and milling, suggesting that Béla ate baked bread and boiled semolina — everyday foods of medieval nobility.

The Journey of His Life

By studying strontium isotope ratios in Béla’s teeth and bones, researchers could trace his movements through geography. Strontium enters the body through food and water, and its isotopic signature reflects the geological composition of the region where a person lives.

The data showed that Béla was not born on Margaret Island. His early years were spent in the region of Vukovar and Syrmia — part of the Macso Banat, which he ruled in name as Duke. Later, as a child or adolescent, he moved northward, perhaps to the royal court near present-day Budapest. His life path mirrored that of many medieval nobles: born in one corner of the realm, educated and groomed for power in another.

The Genetics of Royal Blood

The heart of the project lay in the genetic analysis conducted by Anna Szécsényi-Nagy and Noémi Borbély at ELTE’s Institute of Archaeogenomics. Through advanced sequencing of ancient DNA, they compared Béla’s genetic profile with that of known Árpád descendants and modern genetic databases.

The results were clear and astonishing. The man buried on Margaret Island was indeed Béla of Macsó. His genome revealed the unmistakable signature of Árpád and Rurik ancestry: nearly half of his DNA carried a Scandinavian component consistent with the northern origins of the Rurik dynasty, while another portion reflected Eastern Mediterranean heritage — a legacy of his Byzantine grandmother.

Y-chromosome analysis confirmed his paternal lineage as Rurikid. Remarkably, recent studies from Russia identified the same genetic markers in the remains of Dmitry Alexandrovich, a 13th-century Rurikid prince, confirming the dynastic connection. Béla’s bloodline could thus be traced directly to Yaroslav the Wise, one of medieval Europe’s most powerful rulers.

For the first time, modern science had united centuries of genealogy with hard biological evidence, illuminating the genetic tapestry of two great royal houses.

The Final Moments of a Duke

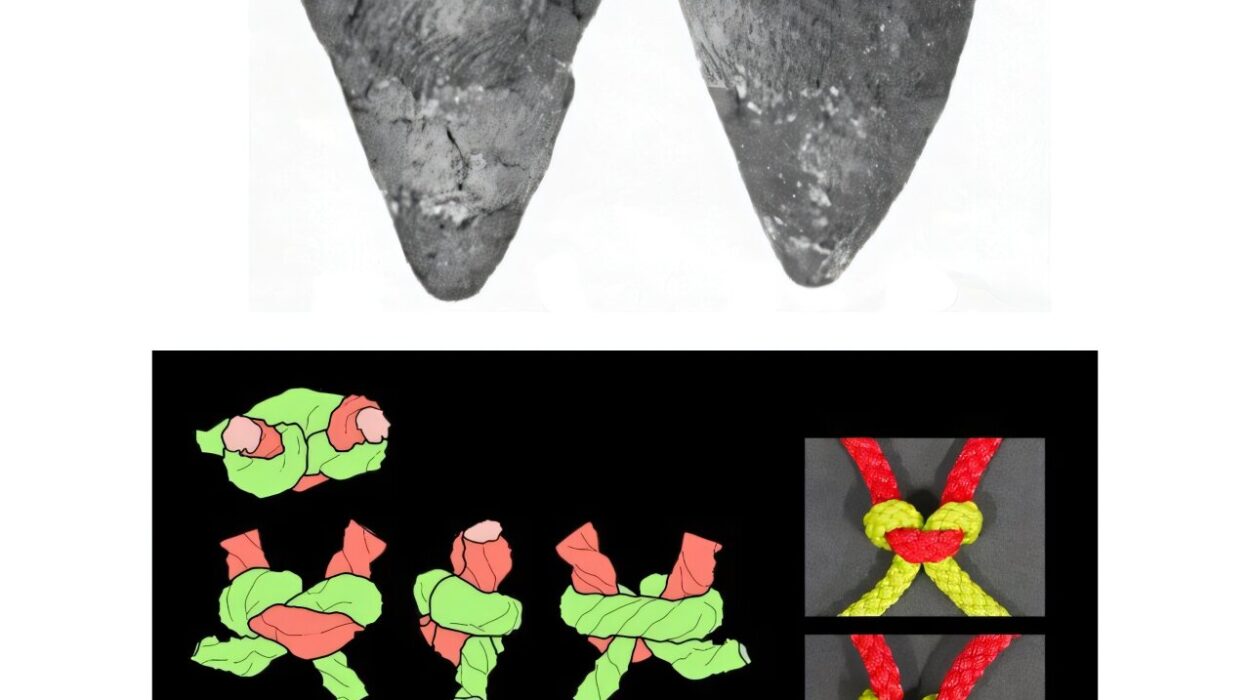

While genetics revealed who he was, forensic analysis revealed how he died. The investigation found 26 perimortem injuries — wounds inflicted at or near the time of death. Nine struck the head; seventeen marked the body. The evidence painted a picture not of a duel, but of an ambush.

Three attackers likely surrounded Béla. One struck from the front, the others from the sides. The cuts to his arms and hands showed desperate attempts to defend himself. Deep gashes to the skull indicated that the final blows came when he was already on the ground.

The weapons were identified as a saber and a longsword — the instruments of knights and assassins alike. The ferocity of the attack, especially the mutilation of his face, spoke of rage and personal hatred. Yet the precision of the assault also suggested planning and coordination. This was not a random killing; it was a political execution carried out with both passion and intent.

As forensic scientists reconstructed the final moments of Béla’s life, they restored more than just a narrative of violence. They gave form to his courage — a young nobleman who, surrounded and unarmed, faced his killers head-on.

Bridging the Past and the Future

The rediscovery of Béla of Macsó’s remains stands as one of the most significant achievements in Hungarian historical science in decades. Apart from King Béla III, his is the only nearly complete skeleton of an Árpád descendant ever confirmed. His bones not only connect two dynasties but also two eras — the medieval world of kings and knights, and the modern world of molecular genetics and forensic anthropology.

Through this research, history and science converged in a remarkable dialogue. Archaeology unearthed the bones; anthropology read their silent testimony; genetics spoke the truth of lineage; and history gave context to every scar. Together, these disciplines wove a narrative that transcends time — a story of loss, rediscovery, and redemption through knowledge.

The Meaning of the Discovery

To identify Béla of Macsó is not simply to put a name to ancient bones. It is to bridge the gulf between past and present, to remind us that history lives not only in chronicles but in the human body itself. The duke’s life, though cut short by betrayal, continues to speak across seven centuries — a testament to both the fragility and the resilience of human legacy.

His rediscovery is also a triumph of cooperation. Scholars from Hungary, Austria, Italy, Finland, and the United States joined forces, proving that the greatest insights often arise when the humanities and the sciences walk hand in hand. Their work reaffirms a profound truth: understanding humanity requires both numbers and narratives, both evidence and empathy.

The Duke Lives Again

Today, the bones of Béla of Macsó rest not in anonymity but in recognition. He is no longer a lost prince, but a person — a young man of royal blood, born between dynasties, whose life was caught in the storm of medieval politics.

Through science, his story has been revived, his voice heard once more in the halls of history. His remains speak not of death, but of discovery — a reminder that even centuries after the final heartbeat, truth endures.

And so, Duke Béla of Macsó, grandson of kings and son of warriors, lives again — not in castles or chronicles, but in the fusion of past and present, memory and science. His bones tell the story that time tried to silence: the story of a life interrupted, and of knowledge that refuses to die.

More information: Tamás Hajdu et al, Murder in cold blood? Forensic and bioarchaeological identification of the skeletal remains of Béla, Duke of Macsó (c. 1245–1272), Forensic Science International: Genetics (2026). DOI: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2025.103381