The Celts stand as one of the most fascinating and enigmatic peoples of ancient Europe. For centuries, they lived, fought, traded, and thrived across a vast territory stretching from the British Isles to the fringes of Anatolia. Yet unlike the Greeks and Romans, the Celts left behind no great written histories of their own. Instead, their story survives through fragments—archaeological finds buried in the earth, accounts written by outsiders, and echoes preserved in myth and folklore.

They were warriors, artisans, farmers, and poets. They painted themselves in vivid colors before battle, fought with ferocity, and terrified even Rome, the most disciplined military power of the ancient world. But they were also a people of deep spirituality, revering the natural world, crafting exquisite jewelry, and sustaining rich oral traditions carried by bards and druids.

To speak of “the Celts” is not to describe a single unified nation but a mosaic of tribes and cultures bound by language, art, and worldview. Their story is not just one of warriors clashing with empires, but also of survival, creativity, and legacy. The Celts shaped Europe’s ancient past, and their echoes remain alive in its cultural heart today.

Origins of the Celtic World

The roots of Celtic culture stretch deep into the European Iron Age. Around 1200 BCE, Europe entered a new era defined by iron tools, weapons, and social transformations. Archaeologists trace the beginnings of Celtic identity to the Hallstatt culture (named after a site in modern Austria), flourishing from about 800 to 500 BCE. Here, evidence of chieftains’ burials with elaborate weapons, wagons, and treasures reflects a warrior elite who commanded both military strength and prestige.

The Hallstatt people spoke early Celtic languages, part of the wider Indo-European family. Their settlements and trade networks linked them with the Mediterranean world. Salt mines, especially at Hallstatt itself, provided wealth and power, enabling the growth of warrior aristocracies. By the 5th century BCE, the Hallstatt culture evolved into what archaeologists call the La Tène culture, centered around Switzerland and spreading outward into France, Germany, Britain, and beyond.

The La Tène Celts became famous for their art—spirals, curving patterns, and stylized animals—decorating weapons, shields, jewelry, and everyday objects. This was the Celtic golden age, when tribes expanded their territories, traded with Greeks and Etruscans, and came into history’s spotlight as both allies and adversaries of empires.

Warriors of Renown

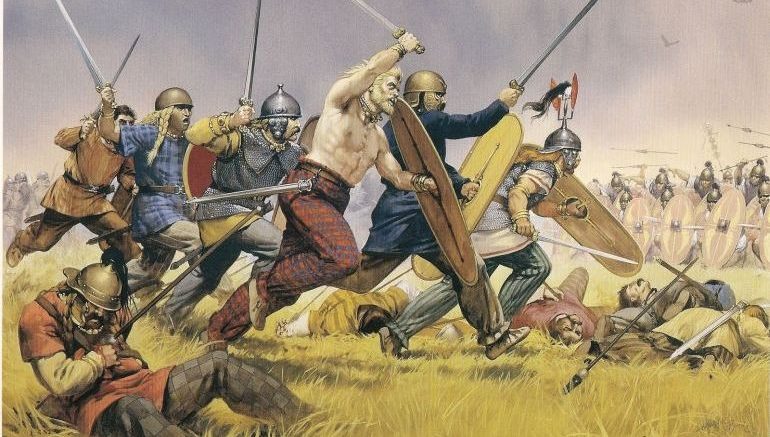

The Celts earned a reputation as fierce warriors across Europe. Greek and Roman writers often described them with awe and fear. The Celts fought with long iron swords, oval shields, and sometimes hurled spears or slings. They valued personal courage and often engaged in single combat before the larger battle, seeking honor and glory.

Classical sources claim that Celtic warriors sometimes fought naked, their bodies painted with bright dyes such as woad, to terrify enemies and demonstrate fearlessness. While historians debate how common this practice was, it illustrates the Celts’ reputation for ferocity. Their war trumpets, called carnyxes, produced a terrifying braying sound that echoed across battlefields.

Celtic warfare was not only about brute force but also mobility. Many tribes excelled in cavalry, and chariots played a prominent role in Britain and Ireland. For centuries, the Celts were the nightmare of Rome, raiding into Italian territory and even sacking the city of Rome in 390 BCE under the chieftain Brennus. His legendary words—“Vae victis!” or “Woe to the vanquished!”—resonated as a reminder of Celtic might.

Society and Daily Life

Although warriors dominate the historical image of the Celts, their society was far richer and more complex. The Celts lived in tribal communities led by chieftains or kings, often supported by councils of nobles and druids. Their society was hierarchical but not rigidly uniform across regions.

At the heart of Celtic life was the extended family and the tribe. Villages and hillforts dotted the landscape, with roundhouses made of wood, wattle, and thatch. Hillforts served as centers of power, trade, and refuge, often surrounded by defensive walls.

Agriculture formed the backbone of daily life. The Celts grew wheat, barley, and oats, raised cattle, sheep, and pigs, and were skilled in dairying. They brewed beer, consumed mead, and traded surplus goods for Mediterranean wine, which they prized greatly.

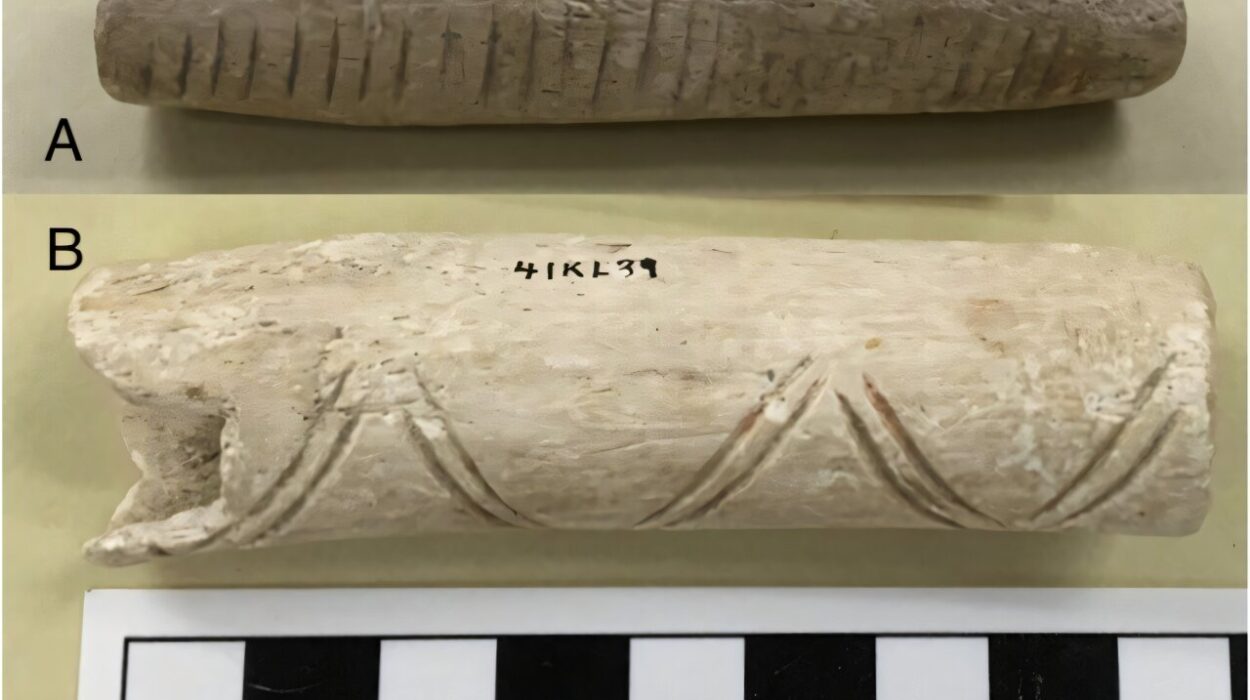

Craftsmanship was highly developed. Celtic blacksmiths produced superior iron weapons and tools, while artisans created jewelry of gold, bronze, and enamel. The La Tène style reflected a love for flowing forms and symbolic designs, suggesting both aesthetic sophistication and deep spiritual meaning.

Women in Celtic societies often enjoyed higher status than in contemporary Mediterranean cultures. Classical sources describe women accompanying men into battle, ruling as queens, and wielding significant influence. Legends like Boudica of the Iceni, who led a rebellion against Rome in Britain, reflect this tradition of female leadership and courage.

Religion and the Druids

Spirituality was central to Celtic life. The Celts saw the natural world as sacred, with rivers, groves, and mountains inhabited by spirits or deities. Their gods were many, often associated with war, fertility, the harvest, or the cycles of life and death. Unlike the Olympian gods of Greece, Celtic deities were more fluid, often merging local and pan-regional characteristics.

The druids held a special place in Celtic religion and society. They were priests, philosophers, judges, and keepers of oral knowledge. Because the Celts left no written records of their beliefs, much of what we know comes from Greek and Roman accounts, especially Julius Caesar, who described the druids in Gaul. They presided over rituals, offered sacrifices, taught oral traditions, and acted as intermediaries between gods and people.

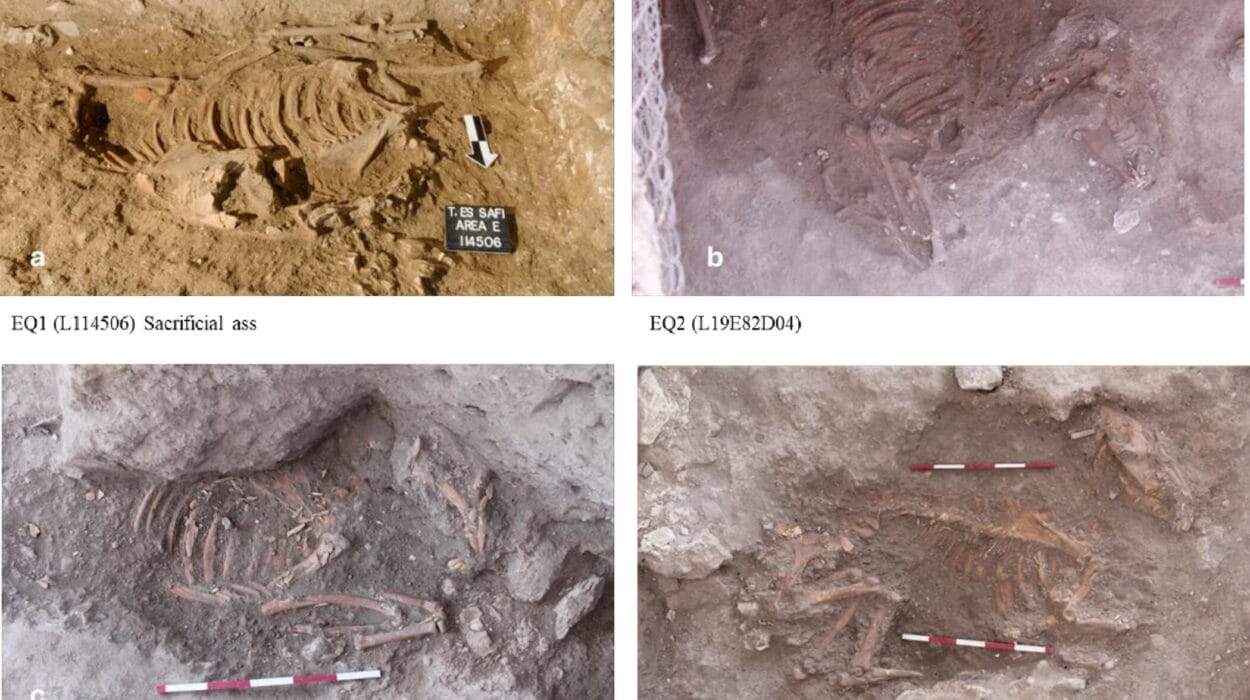

Ritual sacrifice—of animals and perhaps sometimes humans—played a role in Celtic religion. Sacred sites such as lakes and rivers often yielded offerings: weapons, jewelry, and even entire war gear hoards have been discovered underwater, suggesting acts of devotion to deities.

Seasonal festivals marked the Celtic year. Samhain celebrated the end of the harvest and the thinning of the veil between worlds; Beltane marked the fertility of spring with fire rituals. These traditions echo through modern festivals like Halloween and May Day, living remnants of Celtic spirituality.

Expansion and Encounter with Empires

The Celts were not confined to a corner of Europe. During their peak, Celtic tribes spread widely, leaving their imprint from Ireland to Anatolia. In the 3rd century BCE, Celtic warriors moved into the Balkans, fought Greek armies, and eventually settled in Galatia, in modern-day Turkey. St. Paul would later write his biblical letter to the Galatians, descendants of these Celtic migrants.

In the west, Celts dominated much of France (Gaul), the Iberian Peninsula, and the British Isles. They traded with Greeks in southern France and Etruscans in Italy, exchanging tin, slaves, and other goods for wine and luxury items.

But expansion brought them into conflict with the rising power of Rome. The Romans viewed the Celts as both valuable mercenaries and dangerous enemies. The Gallic Wars, led by Julius Caesar in the 1st century BCE, marked the turning point. Caesar’s conquest of Gaul brought most Celtic territories under Roman control, devastating tribal independence but also integrating Celtic lands into the Roman world.

Britain, too, eventually fell to Rome, though not without fierce resistance. Boudica’s revolt in 60–61 CE nearly drove the Romans out, but her defeat marked the decline of Celtic autonomy on the island. Only in Ireland and the Scottish Highlands did Celtic traditions survive largely untouched by Rome.

Art and Culture

Celtic art remains one of the most enduring legacies of this ancient people. Unlike the realism of Greek sculpture or the order of Roman design, Celtic art embraced abstraction, fluidity, and symbolism. Spirals, interlacing patterns, and stylized animals decorated everything from weapons to jewelry to religious artifacts.

The famous Gundestrup Cauldron, discovered in Denmark, showcases elaborate images of gods, animals, and rituals, reflecting the richness of Celtic cosmology. Torcs—neck rings of gold or bronze—symbolized power and status, often worn by warriors and leaders.

Music and oral tradition were equally important. Bards and poets preserved history, myths, and genealogies, passing them down through memorization. Though much was lost with the suppression of druids and the spread of literacy under Roman and Christian influence, Celtic myths later recorded in medieval Ireland and Wales preserve echoes of ancient beliefs. Tales of gods, heroes, and magical worlds—such as the Táin Bó Cúailnge or the Mabinogion—still captivate readers today.

Decline and Transformation

By the first centuries CE, Celtic independence had waned under Roman conquest and Germanic migrations. Gaul became Romanized, adopting Latin language and Roman customs, though Celtic place names and traditions persisted. In Iberia, Celtic and Iberian cultures blended under Rome’s dominance.

Yet in the fringes of Europe, Celtic traditions endured. Ireland, untouched by Rome, preserved a vibrant Celtic culture that would later flourish in early medieval Christianity. Monasteries in Ireland and Wales became centers of learning, preserving not only Christian texts but also echoes of pre-Christian myth and art.

The Celtic languages survived in varying forms, evolving into Irish, Welsh, Breton, and Scottish Gaelic. Today, these languages remain living testaments to an ancient heritage, spoken in communities across the British Isles and Brittany.

Legacy of the Celts

The Celts did not vanish. Their legacy runs deep in European identity, folklore, and cultural imagination. Place names, linguistic roots, and archaeological treasures remind us of their once-vast presence. Festivals like Halloween carry their imprint. The image of the Celtic warrior, wild and unyielding, still captivates modern culture through films, novels, and art.

The Celts also contributed to the story of resistance—resistance against Rome, against assimilation, and later against waves of conquest and change. They remind us of the diversity of Europe’s past, a patchwork of tribes and cultures whose voices, though partly lost, still resonate.

Conclusion: Warriors, Dreamers, and Survivors

The story of the Celts is not simply one of warriors clashing with empires. It is the story of a people who lived close to the land, celebrated the cycles of nature, and left behind an artistic and spiritual legacy that transcends centuries. They terrified Rome, shaped medieval myths, and continue to inspire fascination today.

Though fragmented by history, the Celts endure as warriors of Europe—not only in battle but also in culture, imagination, and spirit. Their story is the story of resilience, creativity, and the timeless human desire to live boldly, to fight fiercely, and to leave behind something that endures.

The Celts remind us that history is not only written by the victors. Sometimes, it is sung by bards, whispered in myths, and etched into the earth, waiting to be rediscovered. And in that rediscovery, the ancient Celts live on.