In the lush countryside of northern Yucatán, hidden beneath centuries of earth and vegetation, archaeologists have uncovered the story of a community that lived only fifteen years yet carried centuries of cultural weight. Hunacti, founded in 1557 and abandoned by 1572, was more than a colonial experiment—it was a battleground of belief, resilience, and quiet resistance.

At first glance, Hunacti appeared to embody the vision of the Spanish Crown. Its grid of streets led to a central plaza crowned by a proud T-shaped church. Elite houses, constructed in European fashion with plastered walls and arched windows, stood as symbols of a future imagined by missionaries and colonial officials. To the casual eye, it was a “model town,” neatly folded into Spain’s expanding empire.

But just beneath the stone streets and plastered walls lay another story: one of Maya endurance, persistence, and subtle defiance.

The Dream of a Colonial Showcase

Hunacti was not an ordinary town. It was chosen as a visita mission site, a place where Franciscan friars would travel from nearby convents to preach, supervise, and enforce Catholic doctrine. Its central church, rising beside older pre-Hispanic pyramids, seemed to declare the triumph of Christianity over Maya traditions.

Historical records reveal that Hunacti’s founding leaders were granted unusual privileges for Maya elites under colonial rule. They had access to horses, a symbol of Spanish power and prestige. They owned a cacao orchard, a crop long tied to wealth and ritual in Maya culture. They commanded significant labor to build the town’s impressive plaza and residences.

Yet such prominence made Hunacti a target for the Franciscan campaigns against “idolatry.” The missionaries, suspicious of Maya elites who held onto their traditions, saw Hunacti as fertile ground for rooting out resistance. What was meant to be a showcase became a stage for persecution.

The Trials of Faith

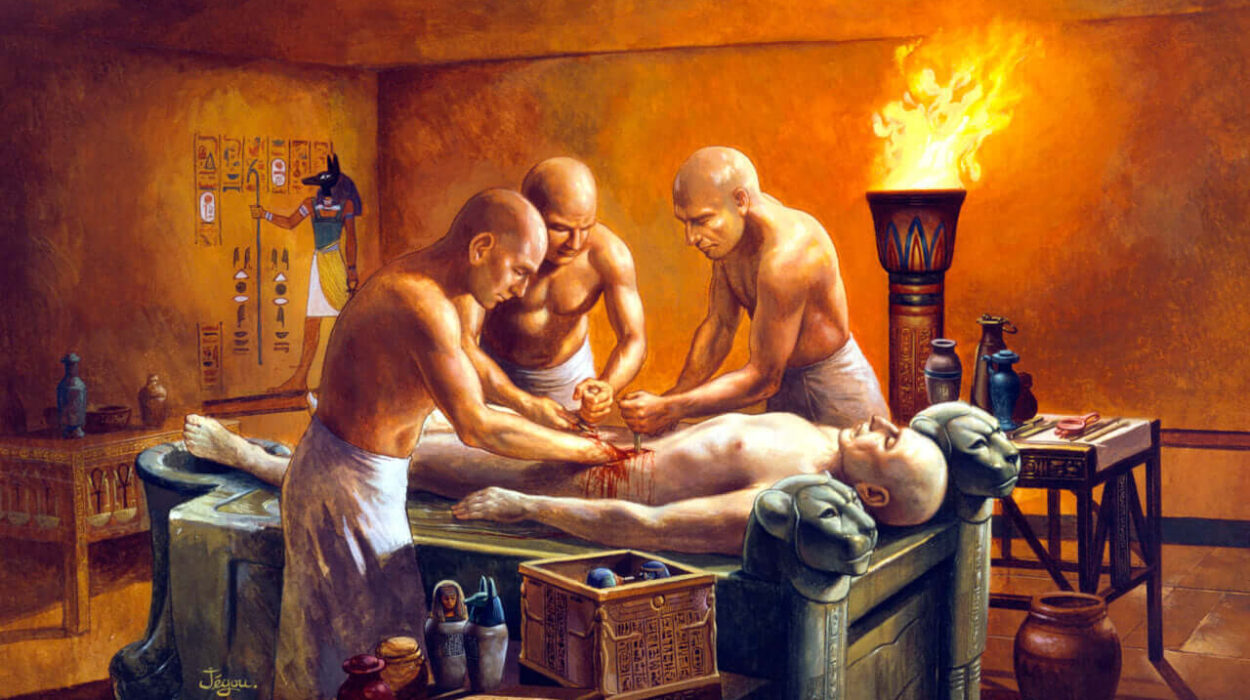

The turning point came in the 1560s, when Franciscan friar Diego de Landa launched infamous “idolatry trials” across Yucatán. These trials aimed to stamp out traditional religious practices, punishing Maya leaders who continued to honor their deities.

Hunacti quickly became entangled in this violent campaign. In 1562, one of its leaders, Juan Xiu, was arrested and tortured to death after being accused of human sacrifice. Others were publicly lashed in subsequent years for similar charges of idolatry. These punishments sent a chilling message: adherence to Maya traditions would be met with cruelty.

An unsettling episode in 1561 may have heightened suspicion. Xiu himself reported the birth of a stillborn infant marked with crucifixion-like scars, a bizarre event that drew even more Franciscan scrutiny. Whether Xiu’s account was a desperate attempt to align with Christian symbolism or a tragic anomaly, it ultimately deepened Hunacti’s vulnerability.

By 1572, famine struck the region, and the town was abandoned. Many of its residents likely relocated to the nearby settlement of Tixmehuac. The grand plaza, once alive with processions and gatherings, fell silent.

The Archaeology of Resistance

Centuries later, the stones of Hunacti still whisper stories that Spanish chronicles never intended to preserve. Excavations led by anthropologist Marilyn A. Masson and her international team reveal that beneath the surface of apparent compliance, Hunacti’s residents held fast to their beliefs.

Within the elite homes and even in the church itself, archaeologists discovered effigy censers—ceramic incense burners adorned with faces of ancient Maya deities. These were not artifacts buried deep from pre-colonial times; many were found above the last colonial floors, showing that residents continued to use them until the very end of the town’s life.

Other discoveries paint a picture of intentional independence. Stone tools were made from local materials, with almost no reliance on European imports—just a single hatchet was recovered. The scarcity of foreign goods suggests the town’s leaders limited their participation in Spanish trade. Animal remains revealed diets that relied on native species like deer, peccary, and iguana, with only a trace of European livestock. Even in the shadow of the church, Maya traditions endured.

A Calculated Autonomy

To colonial authorities, Hunacti’s short life may have seemed a failure. It did not thrive economically, nor did it fully embrace Christianity. But from another perspective, its story is one of resilience and autonomy.

By withdrawing from Spanish trade, maintaining local foodways, and preserving sacred rituals in secret, Hunacti’s leaders crafted a fragile but meaningful independence. They made choices that prioritized cultural continuity over material gain, even when those choices exposed them to persecution and hardship.

In this light, Hunacti’s abandonment was not simply collapse—it was an act of survival. The community carried its traditions to new ground, refusing to let them die in the shadow of empire.

Redefining Success

What does it mean to call a town successful? For colonial rulers, success meant wealth, obedience, and the spread of Christianity. For the people of Hunacti, success meant something different: the ability to sustain their traditions, to worship their gods, to make decisions about their own lives even when under siege.

“Success in this context isn’t just about wealth or imported goods,” Masson explains. “It’s about sustaining your own traditions and making your own decisions, even under intense outside pressure.”

In that sense, Hunacti achieved a kind of victory—not in the eyes of empire, but in the endurance of identity.

The Human Story Beneath the Ruins

Hunacti is more than an archaeological site. It is a reminder of the countless Indigenous communities who faced colonization not passively, but with subtle strategies of adaptation, negotiation, and resistance.

Its story challenges old histories that framed Indigenous peoples as either conquered or converted. The reality is richer and more complex. In kitchens, in household shrines, in the placement of ritual objects, people carved out spaces of freedom even within domination.

Today, as archaeologists sift through broken pottery and scattered bones, they are piecing together a narrative that still resonates. Hunacti speaks not only of suffering but of resilience. It shows that even in a town that lasted just fifteen years, the human spirit found ways to endure.

Legacy of a Forgotten Town

Four and a half centuries after its abandonment, Hunacti continues to speak. Its crumbling church and buried censers remind us that history is not written only by conquerors. It is also written in resistance, in the quiet decisions of communities who refused to let their traditions be erased.

Hunacti may have been short-lived, but it was not forgotten. In its story lies a truth that transcends time: that survival is not only about persistence of bodies, but persistence of belief, identity, and culture.

More information: Marilyn A. Masson et al, Archaeological Perspectives on Confronting Social Change at the Sixteenth-Century Visita Town of Hunacti, Yucatán, Latin American Antiquity (2025). DOI: 10.1017/laq.2025.1