When we imagine alien planets, our minds often drift toward oceans. The concept of “water worlds”—planets covered in endless seas—has fascinated scientists, science fiction writers, and moviegoers alike. Astronomers have long suspected that these aquatic planets are among the most common in the universe, especially because water ice is abundant beyond a star’s “snow line,” the orbital distance at which water freezes.

But what if many of those so-called water worlds aren’t watery at all? What if, instead, they’re made of something darker, stranger, and far more carbon-rich?

A new study led by Jie Li and colleagues at the University of Michigan proposes an alternative: the existence of “soot planets.” Their work, published on the arXiv preprint server, suggests that some exoplanets could be built not from vast reserves of water, but from a material that’s been with us all along—organic carbon dust, also known as soot.

What Exactly Is “Soot” in Space?

When we hear the word “soot,” we picture the black powder left behind after a fire. But in the language of astronomy, soot refers to something more complex: refractory organic carbon. These carbon-based compounds—rich in carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen, or CHON for short—are some of the most fundamental building blocks of chemistry.

Far from rare, soot is surprisingly common in the cosmos. In fact, astronomers estimate that comets, those frozen messengers from the early solar system, are made of up to 40% soot by mass. That abundance suggests that during the birth of planets billions of years ago, soot was everywhere, mixed into the swirling protoplanetary disks of dust and gas.

If comets are time capsules of the solar system’s youth, then soot was one of its most important ingredients. The new research argues that under the right conditions, soot could gather together to form entire planets.

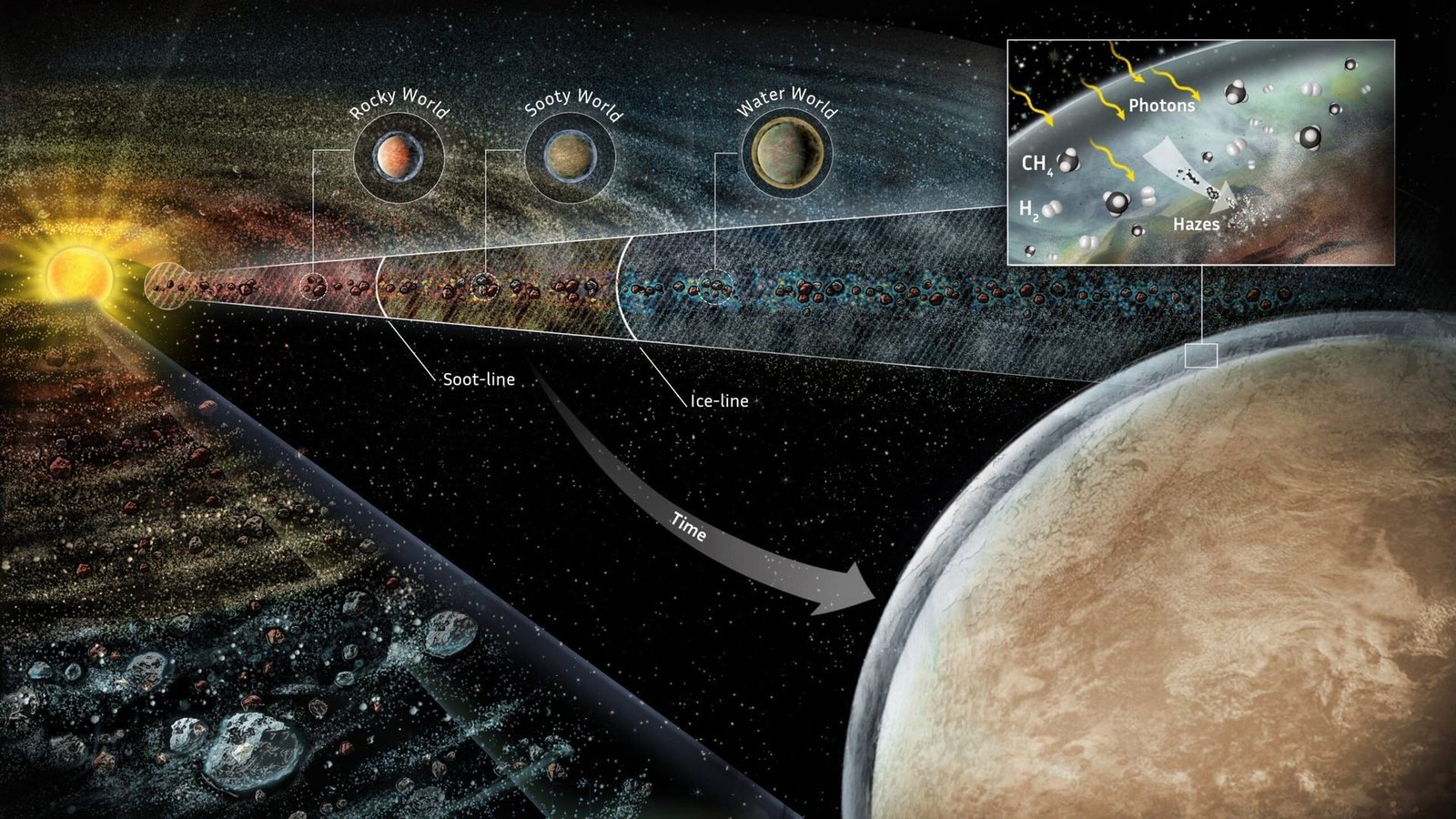

The Soot Line: A New Boundary for Planet Formation

Astronomers have long talked about the “snow line,” the point in a star’s disk where water vapor turns to ice. Beyond that line, icy grains are plentiful, helping planets grow into water-rich worlds.

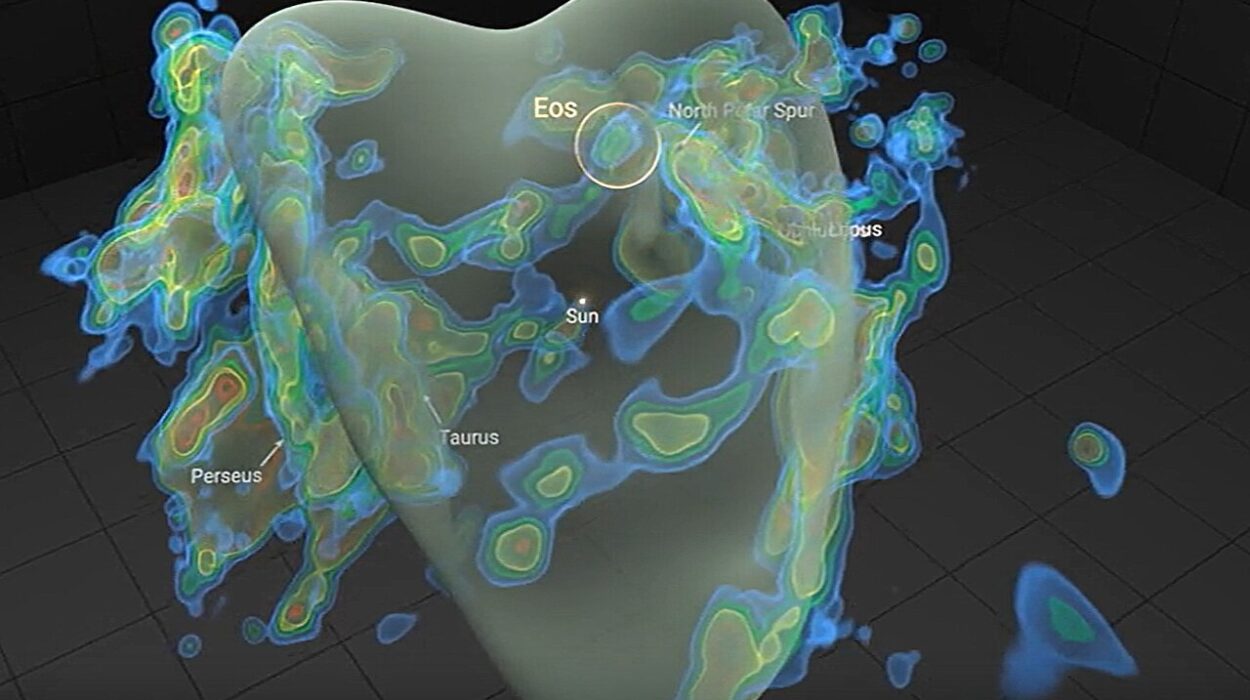

But Li and colleagues propose that there may also be a “soot line.” Closer to the star, it’s too hot for soot to remain stable—it would simply burn away. But past this boundary, soot could survive and clump together. This creates a fascinating new possibility: three distinct zones of planet formation.

- Inner Zone: Too hot for soot or ice, leading only to rocky planets like Earth and Mars.

- Middle Zone (between the soot line and snow line): Planets could form that are dominated by soot but poor in water. They might resemble Titan, Saturn’s moon, with methane-rich atmospheres. Up to a quarter of their mass could be soot.

- Outer Zone (beyond the snow line): Planets would be hybrids—mixtures of water ice and soot. Some could be relatively dry with just 25% water, while others could be half water by mass. Both would still contain 15–20% soot.

These soot-water combinations blur the line between what astronomers once assumed to be straightforward water worlds and what could, in fact, be something entirely different.

The Mystery of Mini-Neptunes

The challenge, however, is that soot worlds and water worlds look nearly identical from a distance. Both can have the same mass and radius, meaning telescopes can’t easily tell them apart. Many of the so-called “mini-Neptunes” already cataloged by astronomers—planets bigger than Earth but smaller than Neptune—may not be water-rich at all, but instead carbon-heavy soot planets.

The only way to know for sure is to study their atmospheres, searching for chemical fingerprints that reveal their true nature.

What the James Webb Space Telescope Is Finding

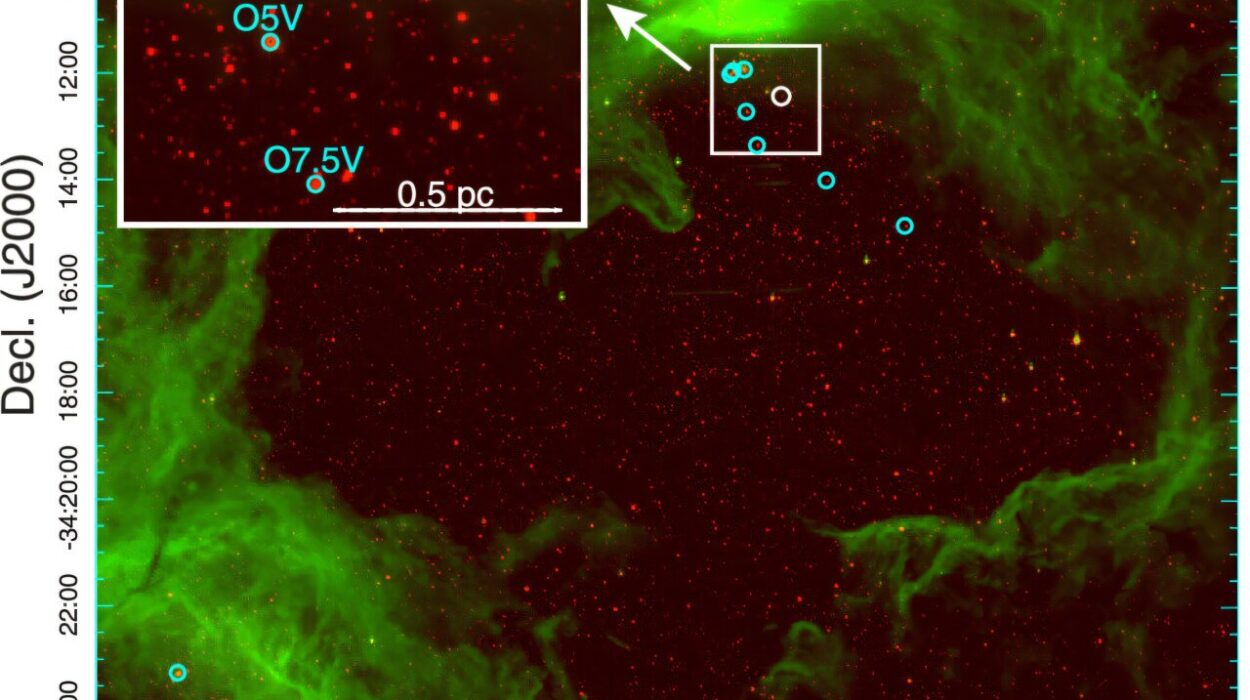

Thankfully, we are entering a golden age of planetary detection. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has already begun sniffing the atmospheres of exoplanets, including a few possible soot candidates.

For instance, JWST detected methane and carbon dioxide in the atmospheres of K2-12b and TOI-280d—two sub-Neptunes that orbit within their stars’ soot zones. The presence of methane and a particularly high carbon-to-oxygen ratio in TOI-280d suggests that it may indeed be a soot planet.

If confirmed, this would be the first evidence of carbon-dominated worlds outside our solar system.

Are Soot Planets Habitable?

The thought of living on a soot planet may sound bleak—dark skies, methane seas, and cores rich in carbon. Yet they may hold tantalizing ingredients for life.

On the downside, soot planets could have diamond-like interiors that prevent efficient circulation of gases and limit the generation of magnetic fields. Without a magnetic shield, life would be vulnerable to deadly cosmic radiation.

On the upside, these worlds would be rich in methane and other organic molecules, the very compounds that may have sparked prebiotic chemistry on early Earth. Though harsh, they might provide laboratories for life’s first steps.

Why It Matters

If soot planets exist, it means that our picture of the galaxy is incomplete. Many of the thousands of exoplanets discovered may not be what we thought they were. Some could be places where carbon, not water, defines the story of planetary evolution.

That has profound implications for how we search for life elsewhere. If life is tied too closely to water, then soot planets may be barren. But if life can adapt to methane, carbon, and alien chemistries, then our universe may be richer in possibilities than we ever dared to imagine.

From Science to Storytelling

There’s a touch of poetry in the idea of soot planets. They are born not from oceans, but from cosmic fire—burnt carbon dust frozen into spheres orbiting alien suns. They remind us that the universe is more creative than our imaginations, building worlds from ingredients we overlook.

And while astronomers will continue probing with telescopes and models, one can’t help but wonder if someday, a storyteller will take inspiration. Perhaps a future science fiction epic will feature explorers sailing methane seas under a sky dimmed by soot, searching for life in the shadows.

Kevin Costner may not return to reprise his role from Waterworld, but maybe—just maybe—the next great space film will be called Sootworld.

More information: Jie Li et al, Soot Planets instead of Water Worlds, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2508.16781