Around 40,000 years ago, two species of humans walked the same lands, hunted the same animals, and gazed at the same night sky. One of them was us—Homo sapiens, the species that would go on to dominate the planet, shaping landscapes, building civilizations, and eventually launching satellites into orbit. The other was the Neanderthals, Homo neanderthalensis, our close cousins who had thrived in Europe and parts of western Asia for hundreds of thousands of years before mysteriously disappearing.

The story of Neanderthals versus Homo sapiens is not a simple tale of competition and conquest. Archaeology reveals a more nuanced picture: one of shared ancestry, cultural exchange, environmental challenges, and perhaps even cooperation. To understand what archaeology tells us about these two species is to peer into a mirror of humanity’s past, seeing both our reflection and the shadow of what might have been.

Who Were the Neanderthals?

Neanderthals first appeared around 400,000 years ago, descending from earlier human species that had migrated out of Africa into Europe. They were adapted to life in Ice Age environments: stocky, strong, with broad ribcages and shorter limbs to conserve heat. Their skulls were elongated, with pronounced brow ridges and large noses, perhaps adaptations for warming cold, dry air before it entered their lungs.

For decades, Neanderthals were caricatured as brutish cavemen—slow-witted, clumsy, incapable of higher thought. This stereotype, born in the 19th century and fueled by early misinterpretations of skeletal remains, has been dismantled piece by piece by archaeological discoveries. Neanderthals were not primitive; they were human. They made tools, buried their dead, controlled fire, and may have painted caves long before Homo sapiens arrived in Europe.

The Rise of Homo sapiens

While Neanderthals were adapting to Europe, our own species was evolving in Africa. By around 300,000 years ago, Homo sapiens had emerged, distinguished by lighter builds, rounded skulls, smaller faces, and, most importantly, a capacity for symbolic thought and complex language.

Archaeological evidence from Africa shows that Homo sapiens were making sophisticated tools, ornaments, and cave art tens of thousands of years before migrating into Eurasia. By 60,000 years ago, waves of modern humans began leaving Africa, spreading across Asia, Europe, and eventually the entire globe.

When Homo sapiens arrived in Europe about 45,000 years ago, Neanderthals were already there, having survived in harsh climates for millennia. For a brief period, the two species shared the continent. What happened next has become one of archaeology’s most captivating mysteries.

Encounters at the Edge of Survival

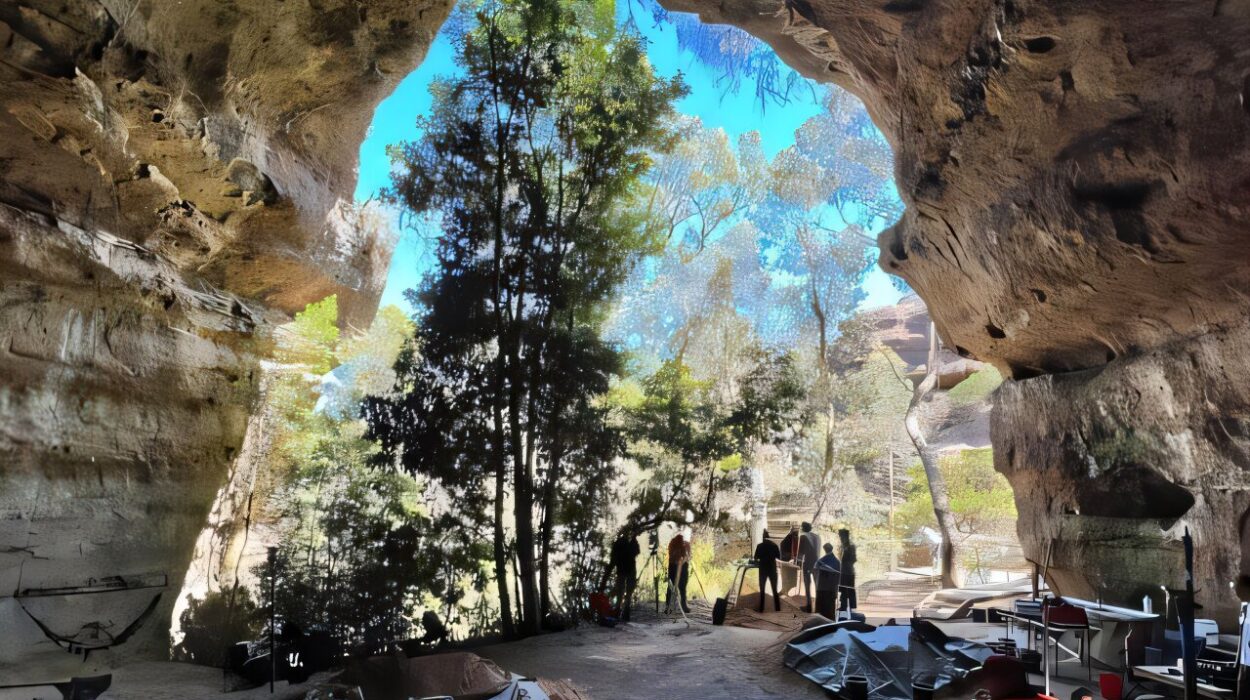

The meeting of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens was not a single event but a long period of interaction. Archaeological sites across Europe and the Middle East reveal overlapping occupations. In caves, archaeologists find layers of artifacts—some made by Neanderthals, others by Homo sapiens—sometimes separated by only a few centuries, or even decades.

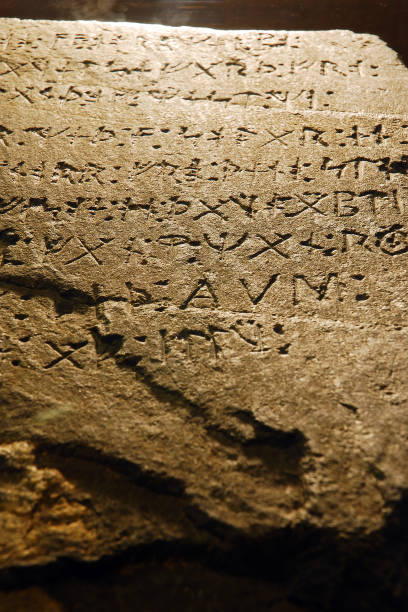

Neanderthal stone tools, part of what archaeologists call the Mousterian tradition, were finely crafted and effective. Yet when Homo sapiens arrived, they brought with them blade technologies, bone needles, and ornaments made of shells and animal teeth. These items hint at symbolic behavior—signs of identity, ritual, and perhaps even spirituality.

But interaction did not necessarily mean conflict. Genetic evidence shows that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens interbred. Today, every person of non-African ancestry carries between 1% and 2% Neanderthal DNA. This genetic legacy influences traits such as immune response, metabolism, and even skin and hair characteristics. Far from being entirely separate, our species were entwined in both biology and culture.

Shared Humanity: What Archaeology Reveals

Archaeology challenges the idea that Neanderthals were inferior. Evidence shows they were skilled hunters, capable of bringing down mammoths, bison, and deer with strategic planning. They used fire to cook food and may have used medicinal plants. Some Neanderthal sites even show traces of pigments and possible body ornamentation.

Burial sites add a haunting dimension. At Shanidar Cave in Iraq, archaeologists discovered Neanderthal skeletons dating back 60,000 years. One individual had injuries that would have left him disabled, yet he lived for years, suggesting care from his community. Another burial site contained pollen grains, sparking debates about whether Neanderthals placed flowers with their dead. Whether or not this interpretation holds, the evidence suggests Neanderthals were capable of empathy, ritual, and symbolic thought.

The Disappearance of the Neanderthals

Despite their resilience, Neanderthals vanished around 40,000 years ago. The reasons remain one of archaeology’s greatest puzzles. Multiple theories have been proposed, and the answer likely lies in a combination of factors.

Climate change was one. Neanderthals had survived numerous glacial and interglacial cycles, but the rapid climate shifts of their final millennia may have disrupted ecosystems, reducing the availability of large game they depended on.

Competition with Homo sapiens may have also played a role. Modern humans, with their wider social networks and more versatile technologies, may have been better at adapting to changing environments. Their ability to create long-distance trade networks could have given them an edge in acquiring resources and forming alliances.

Interbreeding also complicates the picture. Rather than a complete replacement, Neanderthals were absorbed in part into Homo sapiens populations. Their disappearance may not have been a sudden extinction but a gradual merging, leaving behind echoes in our DNA.

Culture Clash or Cultural Exchange?

One of the most intriguing debates in archaeology is whether Neanderthals independently developed symbolic behaviors or whether these arose through contact with Homo sapiens.

Some sites show evidence of Neanderthal cave art predating the arrival of modern humans in Europe, such as painted red symbols in Spanish caves dated to over 60,000 years ago. If these interpretations are correct, Neanderthals engaged in symbolic expression before encountering us.

Other evidence suggests cultural exchange. Tools and ornaments found in transitional archaeological layers may represent Neanderthals adopting ideas from Homo sapiens, or vice versa. Far from a simple “clash of cultures,” the evidence points toward a period of blending, where both species learned from one another.

The Archaeological Lens on Survival

Archaeology is more than a collection of artifacts; it is a window into lives once lived. When we compare Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, we are not looking at two starkly different beings but at variations of humanity shaped by environment and circumstance.

Neanderthals’ robust builds and survival skills were perfect for Ice Age Europe, while Homo sapiens thrived on adaptability and social complexity. Our species’ greater capacity for symbolic thought, larger social groups, and perhaps more intricate language may have allowed us to navigate environmental challenges more effectively. Yet the archaeological record also tells us that Neanderthals were not far behind. The gap between the two species was narrower than once believed.

What Neanderthals Teach Us About Ourselves

The story of Neanderthals is not merely about a species that vanished—it is also about what it means to be human. Neanderthals remind us that intelligence and empathy are not uniquely ours. They cared for the sick, buried their dead, and perhaps created art. They remind us that survival is fragile, that even a species well-adapted to its environment can disappear.

At the same time, their legacy lives on in us. The Neanderthal genes woven into our DNA carry ancient stories of encounters, families, and shared lives. Archaeology allows us to imagine a world where two kinds of humans walked side by side, sometimes competing, sometimes cooperating, always surviving as best they could.

The Mystery That Endures

Despite decades of research, the Neanderthal story remains unfinished. New archaeological discoveries continue to reshape our understanding. Each bone fragment, each tool, each cave painting adds depth to the picture. Were Neanderthals capable of fully modern symbolic thought? Did they sing, tell stories, laugh? How much did they contribute to our own cultural evolution?

What is clear is that the line between “us” and “them” is thinner than ever imagined. Neanderthals were not failed humans—they were a different kind of human, one whose fate diverged from ours but who continues to shape who we are today.

Conclusion: Two Paths, One Legacy

The story of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens is not a tale of winners and losers. It is a tale of two human species shaped by their environments, meeting in a world that was both harsh and beautiful. Archaeology shows us that Neanderthals were intelligent, capable, and deeply human. They vanished, but not entirely—part of them lives on in us.

When we study Neanderthals, we are studying ourselves: our origins, our adaptability, our fragility. Their story is a reminder that humanity is not fixed but evolving, shaped by chance, climate, and connection. Neanderthals walked this Earth, hunted its animals, painted its caves, and dreamed its dreams. Though their voices are silent, the echoes remain, carried in bones, artifacts, and the very strands of our DNA.

Theirs is not a story of defeat, but of kinship—a chapter in the long, unfinished book of what it means to be human.