In the heart of Naples, beneath layers of history and geological shifts, stands the Temple of Venus—a monument that has endured the test of time, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and even the slow sinking of the land beneath it. Almost two millennia after its construction, the temple’s materials continue to defy the forces of nature in ways that modern engineers are still trying to understand. Researchers from the Universities of Naples and Chieti-Pescara were equally intrigued and decided to explore the mystery behind the enduring resilience of this ancient structure.

The Temple of Venus was built in the second century AD under the commission of Emperor Hadrian, during a time when the Romans were known for their advanced engineering skills. It was part of a grand thermal bath complex, an essential part of Roman culture for relaxation, cleanliness, and social interaction. These baths were so important that they even played a role in Emperor Hadrian’s life, as it is believed he constructed them while dealing with an illness. But as fascinating as its history is, what captured the attention of modern-day scientists was the longevity of the materials that made up this Roman marvel, especially considering the temple’s location in a region of constant geological turmoil.

The Temple’s Silent Battle with Nature

The Temple of Venus stands in the Phlegraean Fields, an area famous for its volcanic activity and bradyseism—the gradual rise and fall of Earth’s surface caused by volcanic forces. Over the centuries, this dynamic environment has taken its toll on the temple, sinking it approximately six meters below its original surface. The question remained: How had the materials used to build the temple stood strong, despite the land’s constant shifting beneath it?

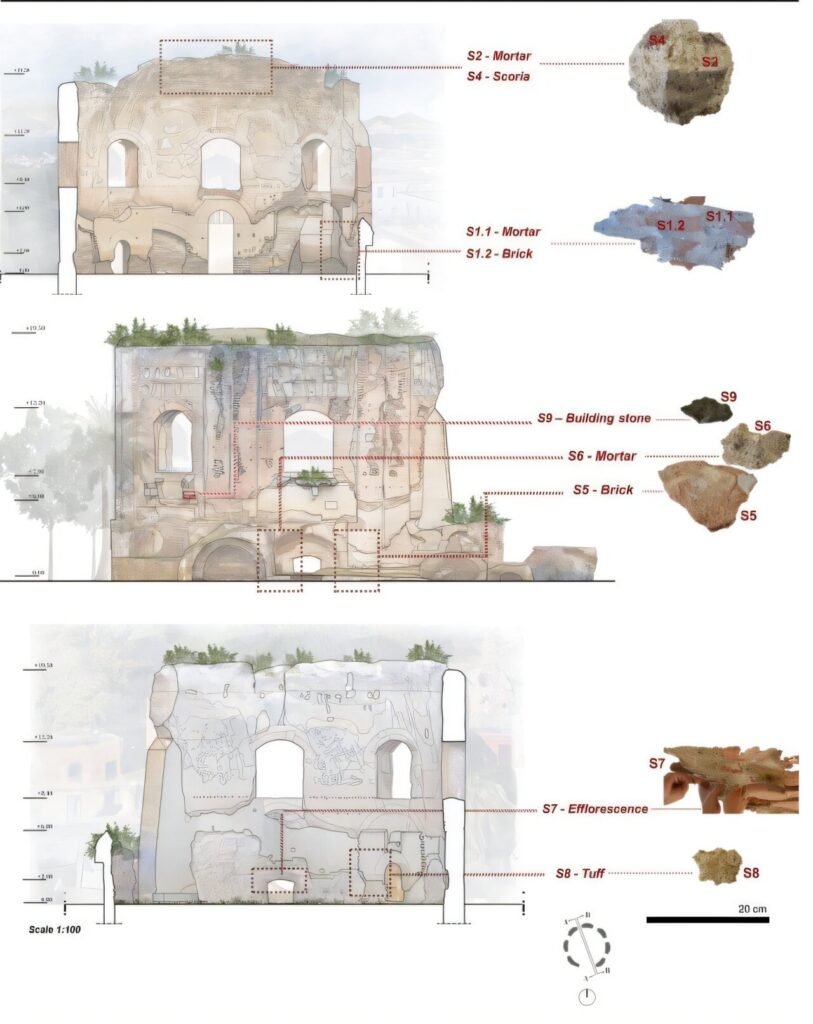

The answer was hidden deep within the very construction of the building. To uncover it, researchers collected samples from across the temple’s structure, including mortar, lava, bricks, and even a mysterious white wall coating known as efflorescence, which forms when salts migrate to the surface of porous materials. They then turned to powerful scientific tools, such as microscopes and X-ray diffraction, to examine the chemical ingredients and the ways these materials had performed over nearly 2,000 years of geologically charged activity.

What they discovered was nothing short of remarkable.

The Ancient Engineers’ Geologic Savvy

The team’s analysis revealed that the Romans were far more than just builders; they were astute engineers who had a deep understanding of the local geology. They had carefully chosen materials that could withstand the unpredictable behavior of the earth beneath them. The mortars, for instance, were lime-based and mixed with a substantial amount of volcanic particles. Volcanic materials were also present in the bricks, mixed with sand-like fragments. The researchers suggest this wasn’t a coincidence or a random choice—it was a deliberate design feature.

In fact, the presence of these volcanic elements was not just a matter of convenience, but a strategic decision. The use of scoria, a lightweight volcanic rock often seen in landscaping or construction today, was sourced from the Vesuvian region, an area known for its active volcanoes. Scoria’s porous structure would have provided strength without adding too much weight, making it an ideal choice for both stability and durability in an area prone to seismic activity.

Unlocking Ancient Secrets for Modern Use

For researchers, the fascination with the Temple of Venus doesn’t end with its historical significance—it extends into the potential lessons that can be applied to modern engineering and conservation efforts. The knowledge gained from examining the temple’s materials opens the door to creating new building materials that could draw on the techniques used by Roman engineers.

The study also offers fresh insight into how we can better preserve the temple itself. Understanding the exact chemical composition of the materials used to build the temple gives experts the tools they need to prevent further degradation and to safeguard other Roman monuments around the world.

“This research doesn’t just shed light on the past,” says one of the lead researchers. “It also opens up new possibilities for modern engineering and material science. The ancient Romans may have been on to something we can learn from today.”

Why This Research Matters

The significance of this research stretches far beyond the Temple of Venus itself. It has the potential to reshape how we think about materials and their ability to withstand geological forces, offering modern engineers new tools to confront the challenges of today’s world. In a time when natural disasters are becoming more frequent and intense, understanding how ancient civilizations built resilient structures could provide us with a sustainable blueprint for the future.

Moreover, the findings offer a glimpse into the ingenuity and foresight of Roman engineers. It’s easy to overlook the wisdom of ancient civilizations, but this research serves as a reminder that there are lessons to be learned from the past, especially when it comes to living in harmony with the forces of nature. The Romans, working without the sophisticated technology available to us today, built structures that have lasted for thousands of years. Their secret? An intimate knowledge of the land they built upon, and a careful selection of materials that would stand the test of time.

By preserving the Temple of Venus and other historical sites with the knowledge gained from this study, we not only protect our cultural heritage but also ensure that the insights from our ancestors continue to shape the world for generations to come. In this sense, the story of the Temple of Venus is not just a tale of a building that survived the forces of nature—it’s a story of human resilience, innovation, and the enduring quest for knowledge.

More information: Concetta Rispoli et al, Innovative Roman Building: Geomaterials, Construction Technology and Architecture of the Roman Temple of Venus (Phlegraean Fields, Italy), Geoheritage (2025). DOI: 10.1007/s12371-025-01208-z