Long before cities rose or empires sprawled, before the wheel turned or metal sang beneath hammer and fire, a vast and frozen wilderness connected continents. This wilderness, now submerged beneath the icy waters of the Bering Sea, once formed a bridge—Beringia—uniting Asia and North America during the last Ice Age. Through this corridor, waves of humans moved eastward into the Americas in one of the most significant migrations in human history.

But what if the story didn’t only flow one way?

For decades, the dominant narrative of early human migration has emphasized a one-directional journey: small bands of hunter-gatherers, driven by cold winds and dwindling game, crossed the Bering land bridge into an unpeopled New World. Yet this narrative left gaps—genetic silences—especially regarding the people who lived on the Asian side of the bridge, in regions like the Altai-Sayan, where the borders of Russia, China, Mongolia, and Kazakhstan now converge. These rugged highlands, where glaciers once groaned and woolly mammoths roamed, are emerging as one of the most important crossroads of early human evolution.

Now, in a landmark study published in Current Biology on January 12, 2024, researchers have decoded the ancient genomes of ten individuals dating back up to 7,500 years, shedding light on a mysterious chapter in human prehistory. Their findings upend previous assumptions, revealing not only who lived in North Asia during the early Holocene—but also uncovering unexpected gene flow from the Americas back into Asia. The direction of discovery has changed. The bridge carried footsteps both ways.

Unearthing Hidden Lineages in the Altai-Sayan

The Altai-Sayan region may be geographically remote today, but 10,000 years ago it was humming with life. Hunter-gatherers moved seasonally through its river valleys and mountain passes, their tools and bones buried beneath millennia of soil and silence. It is here that researchers, led by Cosimo Posth at the University of Tübingen and Ke Wang of Fudan University, retrieved the ancient DNA that now speaks across the centuries.

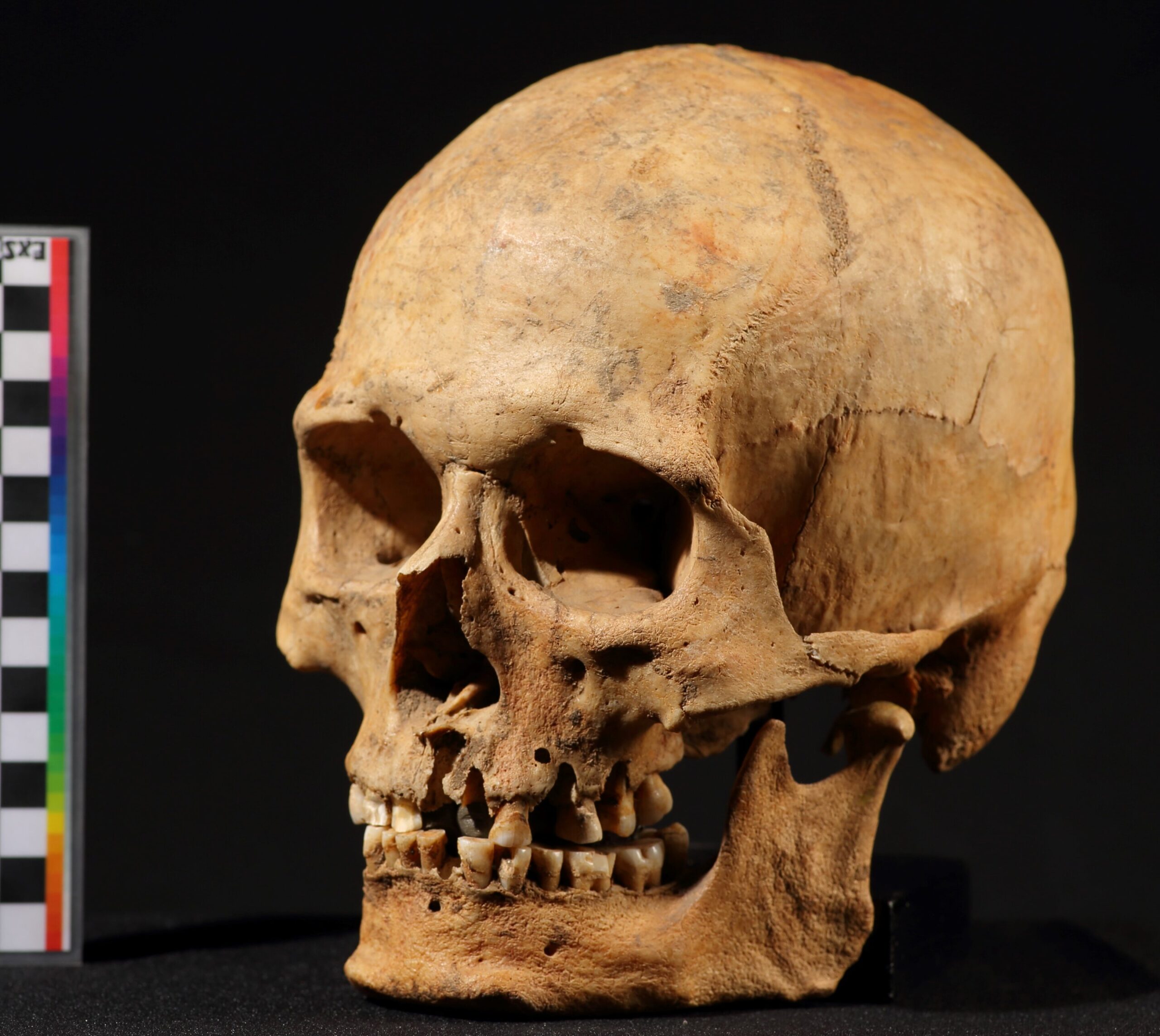

The individuals came from a cluster of archaeological sites rich in stone tools, pottery fragments, and strikingly elaborate burials—including one that may have belonged to a shaman. But it was the genetic tapestry woven into their bones that truly shocked the researchers.

Beneath the surface, the ancient Altaians were not a single homogeneous group. Instead, they were a blend of two Ice Age lineages: the Ancient North Eurasians (ANE)—a ghost population known mostly from the 24,000-year-old remains at Malta near Lake Baikal—and the paleo-Siberians, a group representing older Siberian hunter-gatherer ancestry stretching back into the last glacial period. The fusion of these lineages birthed a new and previously unknown Holocene population in the Altai around 7,500 years ago.

“This is one of the earliest known hybrid populations in Siberia,” Posth explains. “They were highly mobile foragers who not only survived in a harsh and dynamic climate—but helped seed new populations across North Asia.”

A Mirror to the Past: Echoes of American Ancestors in Asia

While the mixture of ANE and paleo-Siberian ancestry was intriguing, it was another twist that astonished the team even more: **genetic signals from ancient North Americans moving westward—**back across the Pacific corridor. These weren’t mere statistical blips. The researchers found clear markers of American ancestry reaching deep into northeastern Asia, especially along the Kamchatka Peninsula and into central Siberia, stretching back at least 5,000 years.

This revelation challenges the assumption that gene flow between continents ceased once the Ice Age ended and the Bering land bridge was submerged. Instead, it suggests that maritime or coastal routes remained active, and that early Arctic peoples—perhaps ancestors of Inuit and Chukchi—continued to travel between the Americas and Asia.

Genetic exchange flowed both ways, weaving a story not of separation, but of long-distance networks, of alliances and movement, of a prehistoric world more connected than previously imagined.

The Nizhnetytkesken Mystery: A Shaman’s Genetic Secret

Among the most enigmatic finds was an individual buried in a cave at Nizhnetytkesken, surrounded by ornate grave goods that appeared to hint at ritual or religious status. This burial was rich with symbolism: objects potentially representing shamanic practices, headdresses, and tools whose cultural motifs were entirely distinct from the surrounding burials.

Yet genetically, this individual didn’t match the Altai population around him. He was genetically closer to Ancient Northeast Asians (ANA)—a lineage previously identified only in Neolithic hunter-gatherers from the Russian Far East, over 1,500 kilometers away.

“This discovery was the biggest surprise,” says Ke Wang. “Here was a person buried with ceremony, who may have been a spiritual figure, and yet his DNA tells a completely different story. He was not local. Whether he came from far away or represented a group nearby with different roots is unclear—but his burial suggests that diverse peoples were interacting culturally and spiritually in the Altai.”

This find underscores how culture and genetics don’t always align. People with vastly different ancestries could share traditions, rituals, and perhaps even languages. In this context, shamanism may have acted as a social glue, transcending genetic boundaries and bringing disparate peoples together under shared beliefs.

The Roots of Bronze Age Societies and the Tarim Mummies

Beyond illuminating isolated individuals, the genetic data also help explain the origins of later, more complex societies across Inner Asia. The Altai hunter-gatherers identified in the study provided key genetic contributions to Bronze Age populations like the Okunevo pastoralists, Lake Baikal hunter-gatherers, and the enigmatic Tarim Basin mummies—famously well-preserved individuals found in China’s western deserts with European-looking features and undeciphered languages.

These connections suggest that the ANE and Altai-related genetic components were crucial in shaping the diverse human patchwork of Central Asia during the Bronze Age. The genetic echoes of Ice Age foragers rippled forward, becoming the ancestral substrate for emerging pastoralist and agrarian cultures as they spread across the steppe.

This refines our understanding of the “Ancient North Eurasian legacy”, long seen as a major contributor to both western Eurasians and Native Americans. With the Altai genomes, researchers now have a clearer picture of how this legacy persisted and recombined through time, helping to shape the genetic contours of modern Siberians, Central Asians, and Indigenous peoples across the Arctic and North America.

Bridging the Biological and the Mythic

The findings also bring new resonance to Indigenous oral histories across the Arctic and Pacific Rim. Many Native American and Siberian groups maintain traditions of migration, contact, and shared ancestry—stories that have often been dismissed as myth. The new data, however, offer a genetic mirror to these narratives, revealing that such migrations did happen, and that cross-continental contact was sustained long after the initial peopling of the Americas.

Even more compelling, the presence of Jomon-associated ancestry—linked to ancient hunter-gatherers of the Japanese Archipelago—in individuals from the Russian Far East shows that maritime mobility extended even into pre-Japanese island societies. Early Holocene humans were not merely land-bound nomads—they were skilled seafarers, with cultural and genetic ties spanning thousands of kilometers.

An Interconnected North Asia, Then and Now

The overarching message of the study is that North Asia was never a forgotten, static frontier. It was dynamic, connected, and peopled by diverse groups who moved, mixed, and reshaped their worlds with each passing millennium. These were not isolated bands clinging to survival—they were migrants, innovators, and storytellers, exchanging ideas as well as genes.

“This region was always a hub, not a backwater,” says Posth. “Even before the advent of agriculture or metallurgy, humans here were engaged in long-range interactions—biologically and culturally. These ancient foragers weren’t the exception. They were the norm.”

Rewriting the Human Story—One Genome at a Time

As ancient DNA technologies continue to evolve, researchers expect to find even more surprises buried in Siberia’s permafrost and steppes. The genomes of the past are opening new chapters in the story of humanity—chapters once believed to be lost.

What makes this study so profound is not just its technical achievements, but the human portrait it paints. The people of early Holocene North Asia were resilient, curious, and mobile, living lives of complexity in one of the world’s harshest environments. They carried with them not only stone tools and fire-making skills, but also languages, myths, and memories—many of which, though unrecorded, still resonate in the genes of their descendants today.

The Altai-Sayan region may lie at the margins of modern geopolitical maps, but for thousands of years it was a beating heart of human migration and interaction. And as we now know, from the swirling rivers of the Yenisei to the volcanic coasts of Kamchatka, from the icy barrens of Beringia to the islands of Japan, the people of ancient North Asia were far more connected than we ever imagined.

In the end, the story of how we became human is not one of isolated branches—but of braided streams, flowing together across time, place, and blood.

Reference: Ke Wang et al, Middle Holocene Siberian genomes reveal highly connected gene pool throughout North Asia, Current Biology (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2022.11.062. www.cell.com/current-biology/f … 0960-9822(22)01892-9