High on the northeastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau, amid the rolling grasslands and rugged hills of China’s Gansu Province, archaeologists have uncovered a story that bridges millennia—a story not of warriors or kings, but of brewers, ancestors, and rituals steeped in the art of fermentation.

At the Bronze Age site of Mogou, dated between 1700 and 1100 BC, scientists have found new evidence that the people who once lived there were master brewers who used an ancient fermentation method known as the qu technique. Their discovery, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports by Dr. Yinzhi Cui and his team, reveals how the Mogou people crafted complex alcoholic beverages long before written history recorded such practices.

This ancient tradition of brewing wasn’t merely for leisure—it was a profound cultural ritual, a bridge between the living and the dead.

The Lost Civilization of Mogou

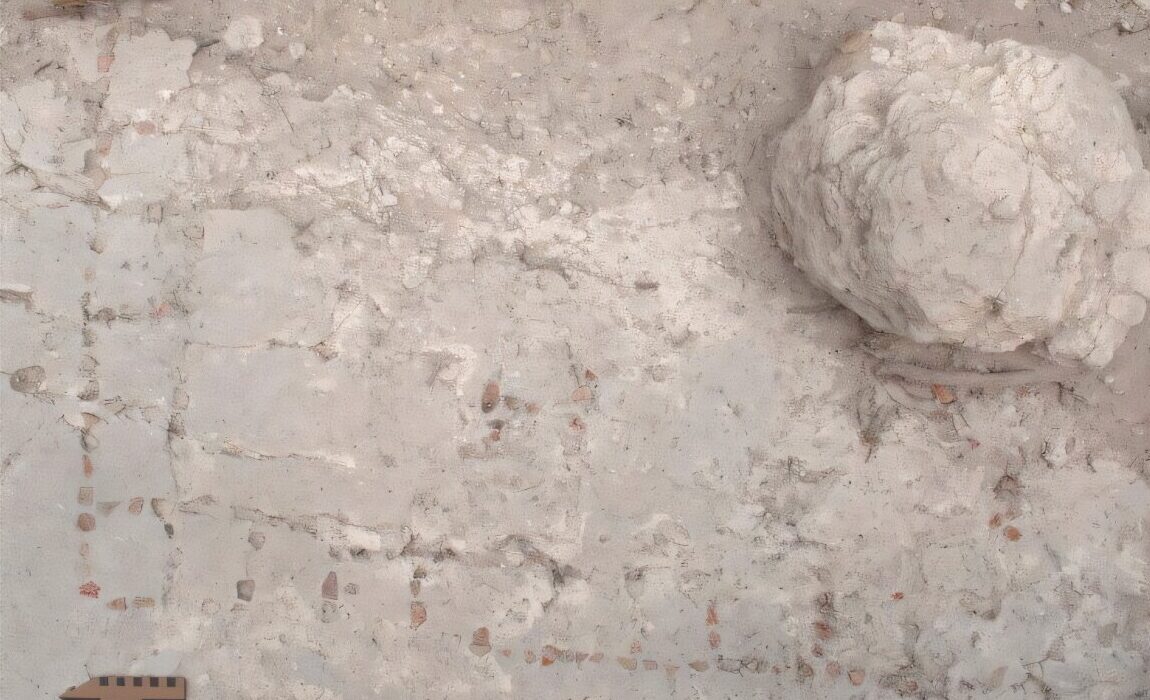

The Mogou site, located in Lintan County, is one of the most significant archaeological discoveries in northwestern China. Excavated between 2008 and 2012, it revealed more than 1,688 graves containing the remains of about 5,000 individuals. These graves spanned two important cultural periods: the Qijia culture (2300–1500 BC) and the Siwa culture (1400–1100 BC).

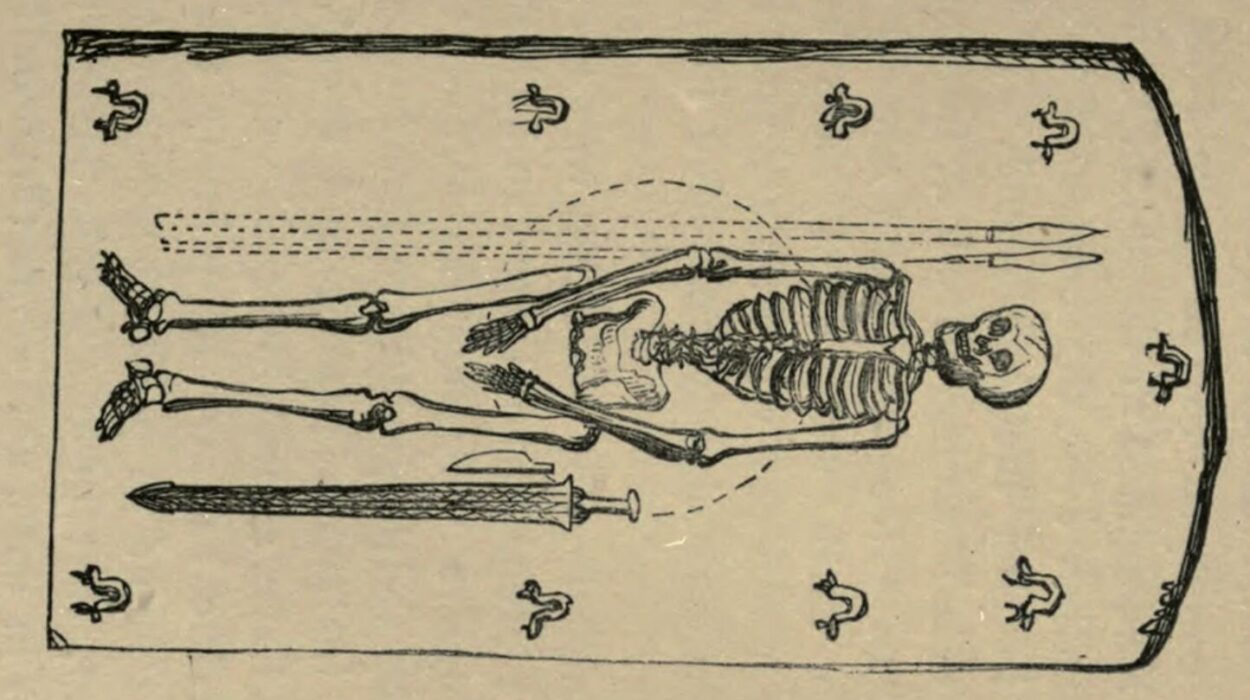

Most of the graves were elaborate catacomb-style burials, with multiple chambers and ceramic vessels placed above the heads of the deceased. These objects weren’t just decorative—they held symbolic, and perhaps even sacred, meaning.

The Mogou site stood at a crossroads of civilizations, where eastern Chinese traditions met the highland cultures of the plateau. It was here, in these burial chambers, that researchers began to find clues of an ancient practice linking daily life to ritual: the brewing and sharing of alcohol.

A Taste of the Past

Dr. Cui and his colleagues set out to analyze the contents of 42 pottery vessels unearthed from Mogou’s tombs. These vessels came from different cultural phases—some belonging to the earlier Qijia culture, others to the transitional period between Qijia and Siwa, and the rest to the later Siwa culture.

Using advanced chemical and microscopic analyses, the researchers examined residue samples from the inside of these vessels. What they found was remarkable. Traces of ancient plants—rice, millet, buckwheat, Job’s tears, barley, and wheat—revealed a diet that was rich and diverse. But among these starches, the scientists also discovered something more telling: microscopic evidence of fermentation.

Under the microscope, many starch granules showed signs of enzymatic digestion, a biological process that occurs during brewing. Even more astonishing, the team found remains of fungi and molds, including hyphae, yeast cells, and Monascus mold, all key indicators of fermentation.

The discovery of Monascus mold, in particular, was a breakthrough—it proved that the people of Mogou used the qu method to brew their alcohol, an ancient fermentation process that originated thousands of years earlier in eastern China.

The Qu Method: China’s Ancient Art of Brewing

To modern readers, “qu” might sound unfamiliar, but it is one of the oldest and most influential brewing methods in the world. Still used in parts of China today, the qu-based technique involves using a fermentation starter made from grains and naturally occurring molds and yeasts.

When mixed with cooked starches such as rice or barley, the qu breaks down complex carbohydrates into simple sugars, which yeast then transforms into alcohol. This process—known as saccharification followed by fermentation—was revolutionary. It allowed ancient brewers to produce consistent, potent alcoholic beverages that could be stored, shared, and used in ritual contexts.

The origins of this method trace back to the Shangshan culture of the Lower Yangtze River (8000–6000 BC) and the early Neolithic cultures of the Yellow River (6000–5000 BC). By the time it reached Mogou during the Bronze Age, the qu method had traveled hundreds of miles and evolved into a deeply symbolic practice.

Brewing and the Afterlife

The Mogou discovery isn’t just about the evolution of brewing—it’s about the meaning behind it. In the ancient world, fermented beverages weren’t simply consumed for enjoyment. They played a central role in rituals, offerings, and social gatherings, often tied to beliefs about life, death, and the afterlife.

At Mogou, the presence of alcohol-related artifacts in graves strongly suggests that brewing was part of mortuary traditions. Archaeologists believe that the Mogou people brewed and offered these drinks to honor their ancestors, seeking blessings or ensuring safe passage into the spirit world.

The act of brewing may have symbolized transformation—the same way raw grains are transformed into intoxicating drink, so too were the dead believed to transform into ancestral spirits. For more than six centuries, from the late Qijia to the Siwa period, this ritual practice remained a vital expression of community identity and remembrance.

A Bridge Between Cultures and Eras

The findings at Mogou also demonstrate how ideas and technologies spread across vast distances in ancient China. The qu brewing technique, first developed in Neolithic eastern China, made its way westward along trade and migration routes, eventually reaching the Tibetan Plateau’s edge.

This movement of knowledge mirrors the broader cultural exchanges that defined Bronze Age China. It was a time when people, goods, and ideas traveled between regions—when farmers, potters, and metalworkers shared innovations that shaped civilizations.

At Mogou, the adoption of the qu method wasn’t just a technological change—it was a cultural one. The people who lived there didn’t merely copy a recipe; they wove it into their spiritual and social fabric, adapting it to their own beliefs and customs.

A Glimpse into Ancient Daily Life

Beyond the grandeur of ritual, the discovery also reveals much about daily life in Bronze Age Mogou. The variety of plants found in the vessels—ranging from staple grains like millet to specialty crops like buckwheat and barley—suggests a sophisticated agricultural system and a nuanced understanding of their environment.

These people were skilled at harnessing nature’s resources, cultivating crops suited to the region’s climate, and experimenting with new methods of food processing. Brewing, in this context, was both a craft and a science—a product of curiosity, experience, and cultural continuity.

The Future of Ancient Fermentation Research

Dr. Yinzhi Cui and his colleagues emphasize that their study is a first step in understanding the social and ritual roles of alcohol in early Bronze Age China. “As we plan to incorporate the latest research in the future,” Dr. Cui noted, “it is premature to draw a conclusion now.”

Their cautious optimism reflects the complexity of archaeological science. Each vessel, each microscopic starch grain, tells only part of the story. But together, these fragments create a vivid picture of a civilization both advanced and deeply spiritual.

Future studies will likely expand on these findings, incorporating more samples from underexplored regions and applying new analytical methods. The hope is to uncover how brewing practices evolved alongside changes in culture, trade, and environment across ancient China.

The Legacy of the Mogou Brewers

The people of Mogou are long gone, their language forgotten, their rituals buried beneath layers of earth and time. Yet, through the residue left on pottery, their story still speaks. It tells of communities that honored their ancestors with song and drink, of hands that carefully brewed spirits to bridge the worlds of the living and the dead.

In rediscovering the art of their fermentation, we glimpse something profoundly human—the desire to remember, to celebrate, and to connect.

From the Bronze Age graves of Mogou to the modern glasses we raise today, the act of sharing a drink remains a symbol of togetherness, tradition, and memory. And somewhere in that ancient brew lies the spirit of those who first transformed grains into ritual, leaving behind not just traces of alcohol—but the essence of civilization itself.

More information: Yinzhi Cui et al, Alcoholic beverage offerings at the bronze age mogou cemetery in northwest China: insights from residue analysis, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2025.105455