More than six thousand years ago, long before the rise of cities or written language, people living in what is now Japan crafted intricate fishing nets from plant fibers. These nets were tools for survival, feeding families and sustaining communities. Over time, the nets themselves disappeared—organic materials like fiber rarely survive thousands of years underground. Yet in an extraordinary achievement, researchers from Kumamoto University have resurrected these long-lost artifacts by reading their ghostly traces preserved in clay.

By applying advanced X-ray computed tomography (CT) and clever replication techniques, the team brought into focus what once seemed irretrievably gone: the very structure of prehistoric nets from the Jomon period, which stretched from around 14,000 to 900 BCE. This groundbreaking work marks the first time in the world that such detailed reconstructions of nets from this era have been achieved, offering a rare glimpse into the ingenuity of ancient craftspeople.

Reading the Past Hidden in Clay

The breakthrough came from an unlikely source—fragments of pottery unearthed in Hokkaido, northern Japan, and Kyushu, in the south. During the Jomon period, nets were sometimes pressed into wet clay, leaving behind subtle impressions before the vessels were fired. For centuries, these faint patterns lay unnoticed or misunderstood.

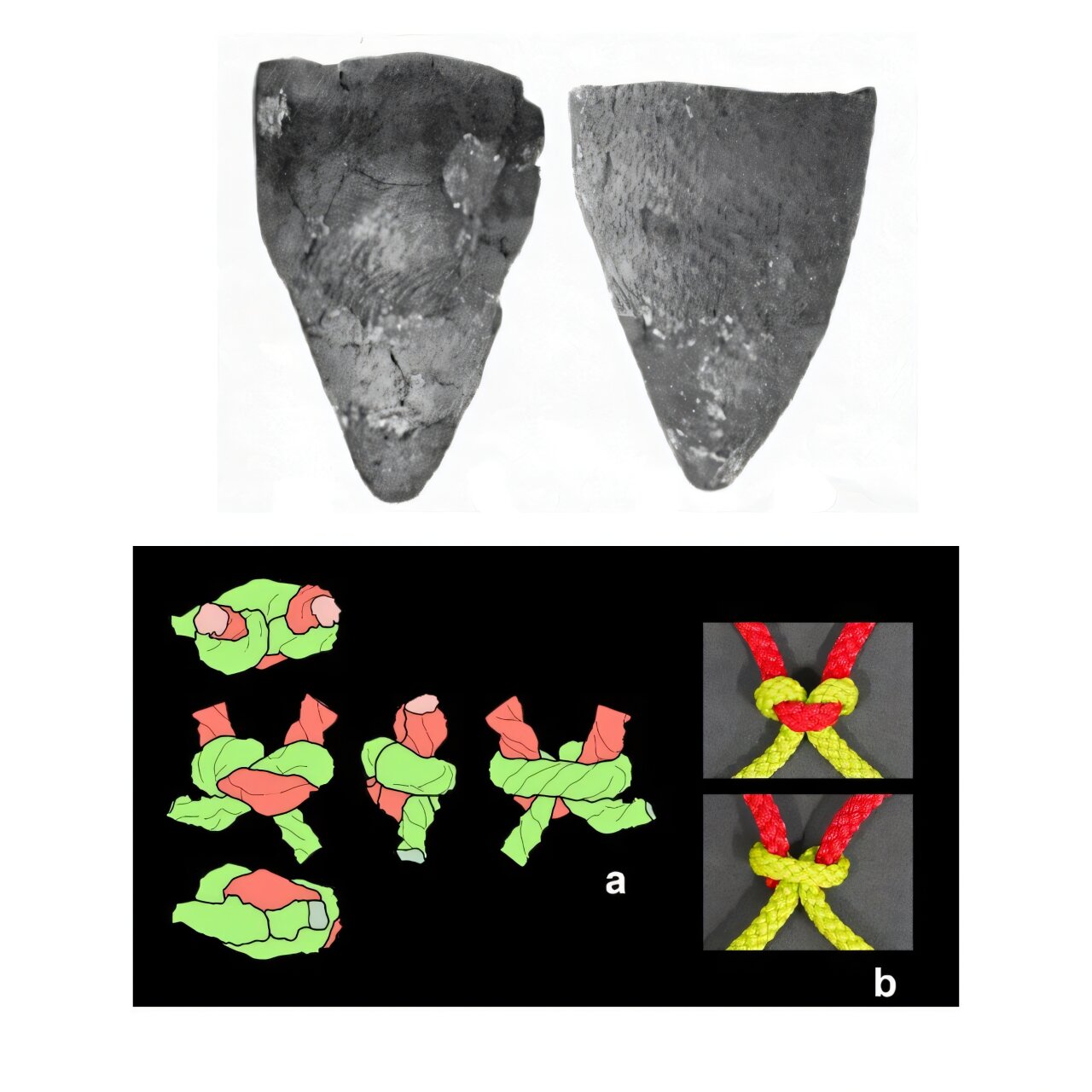

Led by Professor Emeritus Hiroki Obata of Kumamoto University’s Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, the team used high-resolution X-ray CT scanning to peer inside pottery fragments and map the hidden textures of net impressions. Alongside digital reconstructions, they made silicone casts that reproduced the threads, knots, and mesh with astonishing clarity. What emerged was more than an image—it was the revival of a vanished technology.

Two Regions, Two Traditions

The study revealed striking regional differences in net-making traditions. In Hokkaido, the nets impressed into Shizunai-Nakano style pottery displayed large mesh sizes, carefully tied with sturdy reef knots. Such nets were likely designed for fishing in coastal waters, catching larger marine species. But their story did not end in the ocean. Remarkably, these same nets appear to have been repurposed as structural cores for pottery, woven into the very fabric of ceramic vessels. In this, archaeologists see an early example of recycling, where tools gained new life in unexpected forms.

In contrast, pottery from southern Kyushu told a different story. Dating to the Final Jomon and early Yayoi periods, roughly 3,200 to 2,800 years ago, these vessels carried the impressions of fine-mesh nets tied with simpler overhand knots or employing a technique called knotted wrapping. These delicate patterns suggest nets that were used less for fishing and more for carrying—perhaps bags or flexible containers. When pressed into clay, they may have served as molds or release agents during the pottery-making process.

The Human Effort Behind the Nets

The research also shines light on the labor and skill required to make these nets. By analyzing the reconstructed structures, the team estimated that producing a single fishing net could take more than 85 hours of meticulous work. This investment of time underscores not only the practical value of nets but also their cultural importance. To the Jomon people, nets were not disposable objects but vital tools worthy of repair, reuse, and adaptation.

Professor Obata reflected on this aspect of the findings by linking it to contemporary values: “This reuse of materials reflects an early form of sustainability, akin to today’s Sustainable Development Goals.” In other words, long before modern societies began grappling with issues of waste and resource management, the Jomon people were already finding creative ways to extend the life of their tools.

Rethinking What Net Impressions Mean

For decades, archaeologists assumed that all net impressions found on pottery represented fishing equipment. This study challenges that assumption, showing that nets served multiple purposes and lived multiple lives. Some were certainly used in fishing, but others likely functioned as bags, wrappings, or even structural elements in ceramics. The impressions on pottery are not just evidence of tools but traces of a wider material culture—of reuse, innovation, and adaptation.

This insight opens new doors for interpreting similar archaeological finds. Not every net imprint is a relic of fishing; some may represent entirely different practices. By distinguishing between these uses, archaeologists gain a richer understanding of daily life in prehistoric Japan.

Weaving Technology, Past and Future

Perhaps the most extraordinary aspect of this achievement is how it bridges the gap between past and present. With digital reconstructions and physical casts, researchers have not only visualized the nets but also resurrected the knowledge of how they were made. The twists of the threads, the choice of knots, the scale of the mesh—all of these details illuminate the minds and hands of people who lived thousands of years ago.

It is a reminder that technology is not only modern; it is ancient. The Jomon people were engineers in their own right, weaving fibers into complex tools that sustained their communities. Their skill and creativity echo across the millennia, now made visible again by the tools of modern science.

Threads That Connect Us

The discovery of these nets is more than a technical triumph—it is a deeply human story. It tells us about resilience, ingenuity, and the timeless struggle to thrive in challenging environments. It reveals how people adapted to their surroundings, invested enormous effort in their tools, and found ways to reuse and repurpose what they had.

By reconstructing these fragile threads, we are reminded of the threads that connect us across time. The same hands that tied knots in nets six thousand years ago are not so different from ours today. They reveal a shared human impulse: to create, to adapt, and to leave behind traces of our lives in the materials we shape.

Through this study, the silent impressions left in clay have found their voice. They speak not only of fishing and pottery but of a worldview rooted in continuity and care. And in bringing them back to life, science has given us a rare chance to listen.

More information: Hiroki Obata et al, Nets hidden in pottery:Resurrected fishing nets in the Jomon period, Japan, Journal of Archaeological Science (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2025.106231