In the heart of León, Spain, archaeologists made a discovery that challenges long-standing assumptions about life and death in the Roman military. During emergency excavations at the sacristy of the Siervas de Jesús convent and on Francisco Regueral Street in 2006, a small burial emerged from beneath centuries of soil and human activity. Unlike typical military graves lined with armor or weapons, this burial held a fragile, perinatal infant, quietly resting under a tegula, a Roman roof tile.

The burial, located near a doorway within Sector 1 of the Legio VI Victrix castrum, is extraordinary. Roman funerary practices for infants often placed them in domestic spaces beneath floors or in cemeteries outside military zones. Yet here, the infant rested within a space associated with the daily activities of lower-ranking soldiers, a contubernium workshop. This unexpected context immediately raised questions: why was the infant there, and what does it tell us about the lives of those at the fringes of the Roman Empire?

Legio VI Victrix and the Roman Military Frontier

To understand the significance of this burial, we must first step into the world of Roman military expansion. Legio VI Victrix was founded by Augustus in 41 BCE and deployed to Hispania Tarraconensis in 29 BCE. The camp in León occupied a strategic location, controlling passes through the Asturian mountains and guarding the confluence of the Bernesga and Torío rivers. It was a site of military precision, discipline, and regulation, where soldiers were expected to dedicate themselves entirely to service and to leave domestic life behind.

Yet archaeology often reveals the human realities behind these rigid structures. Despite Augustus’s regulations forbidding soldiers from marrying during service, evidence across the Roman Empire—from Britannia to Germania—suggests that women and children often lived in and around military forts. The discovery of an infant burial within a contubernium, therefore, offers a rare glimpse into the lived experience of these frontier communities, where official policy and human necessity collided.

Examining the Life of an Infant Lost Too Soon

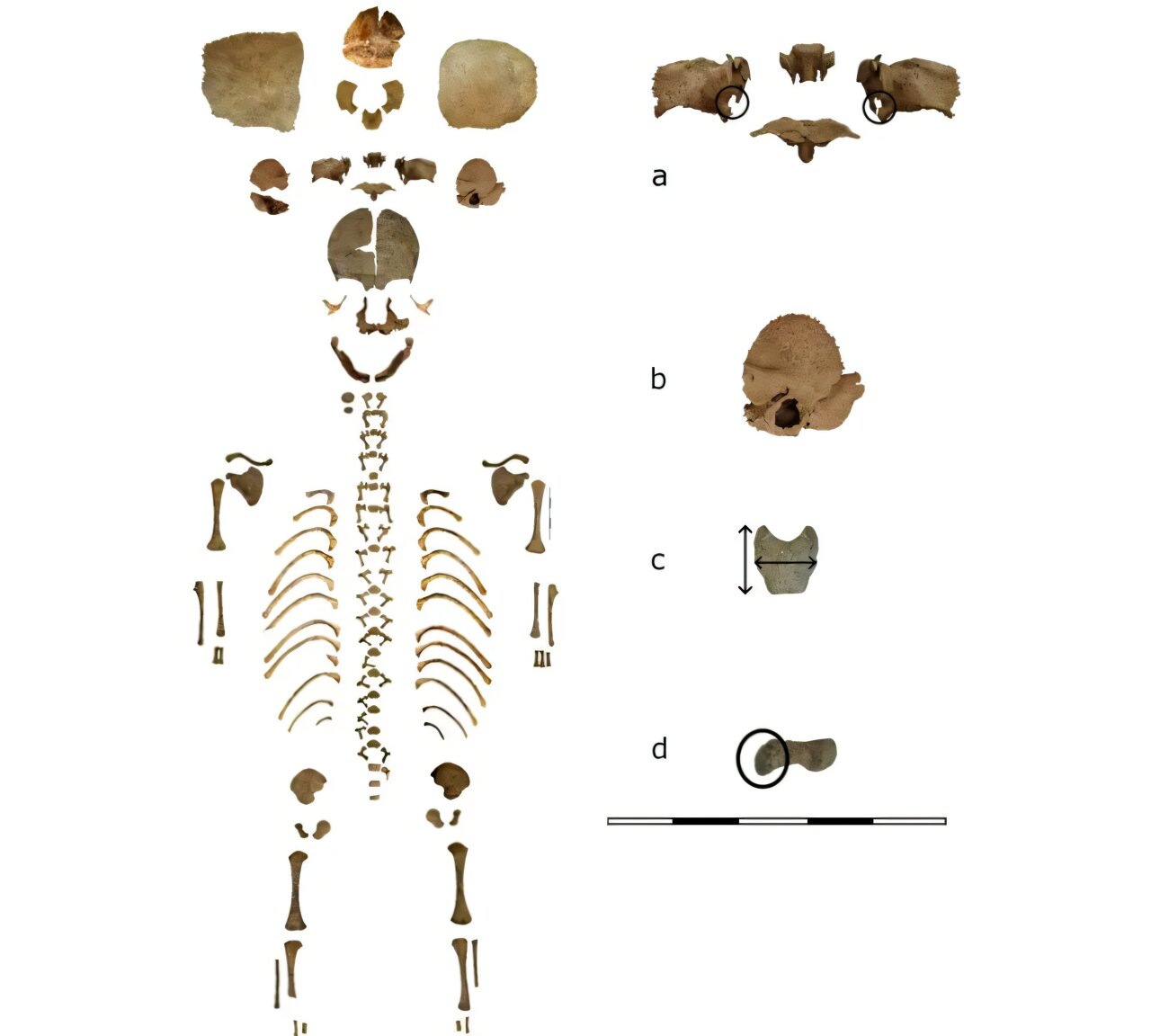

The infant buried at Legio VI Victrix has left silent yet telling traces of its brief life. Although no teeth survived, researchers estimated age through femoral length, suggesting the child was between 38 and 42 weeks gestational age—essentially at full term. Yet an analysis of the skull, hip bone, and base of the skull revealed incomplete development, indicating malnutrition, illness, or stress during gestation.

There were no signs of physical trauma on the bones, suggesting the death was not violent. Still, researchers caution that certain causes—such as smothering or exposure—would leave no skeletal evidence. Radiocarbon dating placed the burial between 47 BCE and 61 CE, a period overlapping with Augustan reforms that strictly regulated the presence of women and children within legionary camps. The child’s presence, therefore, reflects not only biological fragility but also the complex social dynamics at the frontiers of the empire.

Between Law and Life: The Augustan Regulations

Augustus’s legislation, including the Lex Julia and Papia, forbade soldiers from marrying during service, aiming to ensure military focus and discipline. Yet these laws were rarely absolute in frontier territories. Archaeological finds from forts like Vindolanda and Birdoswald in Britain reveal footwear, personal objects, and domestic artifacts associated with women and children within military confines.

The infant burial in León may represent a transitional period, when older customs allowing families within the camp persisted despite new imperial regulations. It may also reflect a pragmatic adaptation: frontier forts often operated on the margins of strict enforcement, where human needs and social bonds coexisted with the demands of military law. In this sense, the infant becomes more than a set of bones; it is a symbol of the tension between imperial authority and human reality.

Ritual, Belief, and the Power of the Perinatal

Beyond legal and social considerations, the burial reflects deeply held Roman beliefs about life, death, and the spirit world. Infants who died at or near birth were considered especially potent spirits, capable of influencing the living. Archaeologists Marta Fernández-Viejo and her colleagues suggest that the infant may have been interred near a doorway as part of a foundation burial, a ritual intended to protect the space and ensure prosperity.

In Roman practice, foundational deposits—whether animal, human, or symbolic—were placed at thresholds or entrances, marking the transition from the profane to the sacred. By situating the infant beneath the tegula in a workshop, the burial may have served to safeguard daily labor, protect the soldiers’ endeavors, and honor spiritual customs surrounding premature death. The small size of the infant does not diminish the significance of its role within these layered cultural practices; if anything, it magnifies the poignancy of the act.

Challenging Traditional Views of Military Life

This burial calls into question the strict separation of military, domestic, and religious spheres in Roman legionary camps. It suggests that, even under Augustus’s strictures, families and infants were present at least temporarily, and that ritual life intertwined with the functional spaces of the fort. The presence of the infant in a contubernium—a place associated with daily work, camaraderie, and subsistence—reveals that military life was never purely mechanical; it was infused with human experience, grief, and belief.

Moreover, the burial underscores the adaptability of Roman soldiers and communities at the empire’s edge. Military discipline coexisted with social practices, family presence, and spiritual rituals, reflecting the complex realities of life on the frontier. It is a reminder that archaeology often uncovers nuance that written law and policy cannot capture.

Insights into Roman Frontier Societies

The infant burial at Legio VI Victrix enriches our understanding of the Roman Empire in several ways. Biologically, it highlights the vulnerability of infants and the stresses of prenatal development in antiquity. Socially, it reveals the persistence of familial structures and domestic life within military spaces, even under legal constraints. Culturally, it illuminates the significance of ritual practice and belief in protecting both spaces and people, particularly the deceased.

At a larger scale, the discovery reminds us that the Roman Empire was not a monolith of rules and regulations but a tapestry of human interactions, customs, and adaptations. Each burial, artifact, or footprint offers a window into a life lived, a belief held, or a grief mourned—a testament to the humanity underlying imperial conquest.

A Story Written in Bones

Archaeology allows us to recover fragments of forgotten lives, and in the case of the infant at León, these fragments tell a story that resonates across millennia. This was a child whose brief presence touched the lives of soldiers and perhaps their families, whose death prompted rituals designed to protect and sanctify, and whose burial reflects a delicate balance between law, custom, and belief.

The Legio VI Victrix burial demonstrates that even the smallest and most fragile lives mattered in the grand machinery of the Roman world. It challenges assumptions about military discipline, family life, and ritual practice, while revealing the deeply human impulses that endure through time: the desire to care for the vulnerable, to honor the dead, and to seek protection from forces both seen and unseen.

More information: Fernández-Viejo Marta et al, Uncovering Childhood in the Roman Army: A Perinatal Burial from the Roman Castrum of the Legio VI in León, Childhood in the Past (2025). DOI: 10.1080/17585716.2025.2538923