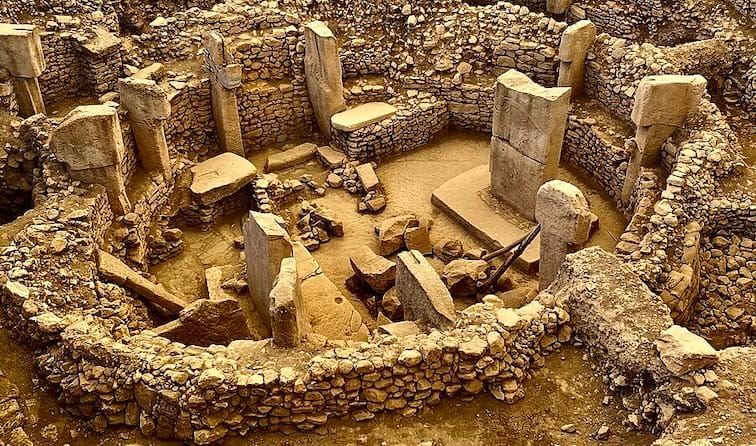

The story of human civilization is inseparable from the story of agriculture. Roughly 10,000 years ago, during the Neolithic period, humanity began its greatest experiment: the deliberate cultivation of plants. This transition from foraging to farming—what historians and archaeologists call the Neolithic Revolution—set the stage for settled communities, complex societies, and eventually the sprawling civilizations that would shape our modern world.

Traditionally, the Fertile Crescent, a crescent-shaped region spanning parts of modern-day Iraq, Syria, Israel, Lebanon, and Turkey, has been considered the cradle of agriculture. Archaeological evidence points to the Natufians, a foraging people of the Levant, as among the first to harvest wild grains like wheat and barley. From these early experiments, humanity began its slow but transformative journey toward domestication, setting the precedent for cultural and technological developments that would ripple across continents.

A Surprise from Central Asia

New research is now expanding our understanding of where and how these transformative behaviors emerged. An international team of scientists, led by Xinying Zhou of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing and guided locally by Farhad Maksudov of the Institute of Archaeology in Samarkand, has uncovered compelling evidence that people in southern Uzbekistan were harvesting wild barley over 9,200 years ago.

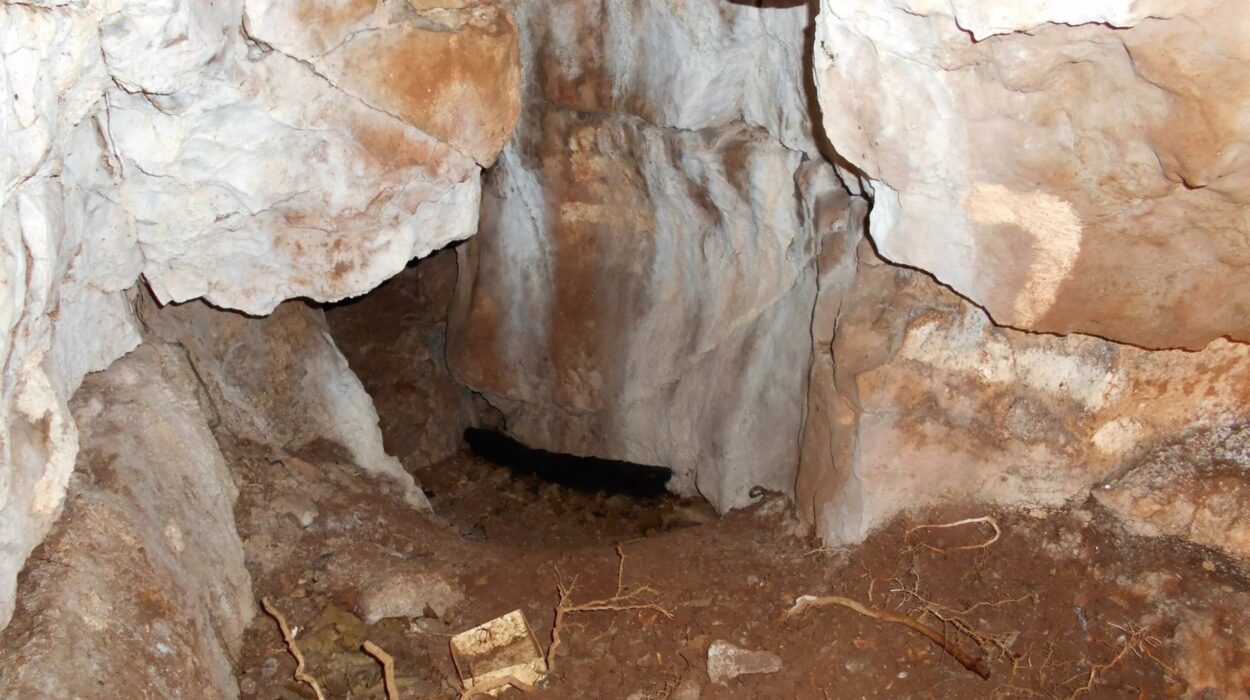

At Toda Cave, located in the Surkandarya Valley, the team discovered stone tools, plant remains, and charcoal from the cave’s oldest layers. Their findings suggest that these ancient foragers were engaged in practices remarkably similar to those that would eventually give rise to full-fledged agriculture. The significance of this discovery lies not merely in its age but in its geographic reach. It indicates that cultural behaviors preceding agriculture were far more widespread than previously understood, challenging the notion that farming arose solely as a local response to population pressures or climate change.

Tools, Plants, and Daily Life

Archaeobotanical analysis led by Robert Spengler of the Max Planck Institute for Geoanthropology revealed a diverse suite of plant remains. Wild barley dominated, but the cave also yielded pistachio shells and apple seeds, pointing to a sophisticated knowledge of local flora. Equally important were the stone tools recovered from the site. Made mostly from limestone, these blades and flakes bore wear patterns consistent with cutting grasses or other plant materials—similar to tools associated with early farming communities elsewhere.

These artifacts suggest that the inhabitants of Toda Cave were not merely opportunistic gatherers; they were engaged in purposeful, repeatable actions that formed the foundation of agricultural practices. The line between foraging and farming, once thought rigid, now appears far more fluid, with communities experimenting with plant collection, processing, and possibly even early cultivation.

Rethinking the Origins of Agriculture

“This discovery should change the way that scientists think about the transition from foraging to farming,” Zhou explains. The Toda Cave findings underscore the idea that the behaviors leading to agriculture were not isolated innovations but part of a broader, interconnected set of practices. Humans, it seems, were experimenting with the very elements of cultivation long before the fully domesticated plants we associate with early farming emerged.

Spengler adds, “These ancient hunters and foragers were already tied into the cultural practices that would lead to the origins of agriculture.” Growing evidence from around the world suggests that domestication may have occurred without deliberate intent. Instead, incremental experimentation and cultural practices over generations gradually transformed wild species into crops. Toda Cave now provides a compelling illustration of this gradual, emergent process.

The Broader Implications

The significance of the Toda Cave discovery extends beyond Uzbekistan. It raises fundamental questions about the spread and development of agriculture. Were these wild barleys being deliberately cultivated, representing an independent experiment in farming, or did knowledge of cultivation practices diffuse eastward from the Fertile Crescent earlier than previously recognized? Either scenario challenges long-held assumptions that agriculture was a single, localized invention.

The possibility of parallel experimentation suggests that humanity’s transition to farming was not a linear process but a mosaic of experiments, insights, and cultural adaptations occurring across vast landscapes. Understanding this complexity reshapes our perception of early human ingenuity and the universality of agricultural innovation.

Connecting Past and Present

Studying ancient plant use is not simply an academic exercise. These discoveries provide insight into the resilience and adaptability of human societies. The people of Toda Cave were responding to their environment with ingenuity and experimentation, laying the groundwork for techniques that would sustain human populations for millennia. By reconstructing these behaviors, scientists gain a window into the cognitive and cultural sophistication of early humans, revealing how our ancestors actively shaped the natural world rather than passively responding to it.

Furthermore, understanding the multiple pathways to agriculture has contemporary relevance. Modern challenges, from food security to sustainable farming, echo the questions faced by early societies: How do we harness nature’s resources without exhausting them? How do cultural practices intersect with ecological realities? The study of Neolithic innovations reminds us that these questions are ancient, universal, and deeply human.

Continuing the Search

The international team continues to explore Toda Cave and surrounding regions to better understand how widespread these behaviors were in Central Asia during the Neolithic. Future research will examine whether the grains found represent early cultivation attempts or reflect knowledge exchange across regions. Either outcome promises to illuminate the complexity of early human subsistence strategies, offering a richer narrative of the transition from foraging to farming.

What is clear is that humanity’s journey toward agriculture was not a singular invention but a collective, iterative process. The story of Toda Cave adds a new chapter to that narrative, demonstrating that human curiosity, creativity, and adaptability have always been at the heart of our species’ survival and success.

A New Perspective on the Origins of Civilization

Toda Cave reminds us that the birth of agriculture was not confined to a single valley or a single culture. It was a mosaic of experimentation, discovery, and cultural refinement occurring across continents. The ancient foragers of Central Asia, like the Natufians in the Fertile Crescent, were shaping the natural world, gradually laying the foundations for settled life, surplus food production, and ultimately, civilization itself.

In understanding these early steps, we gain more than historical knowledge. We glimpse the enduring human spirit: a spirit defined by curiosity, resourcefulness, and the ability to imagine new possibilities. The seeds of agriculture, scattered in caves and valleys thousands of years ago, represent not just the origins of food systems but the origins of human ambition, innovation, and hope.

More information: Zhou, Xinying et al, 9,000-year-old barley consumption in the foothills of central Asia, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2424093122. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2424093122