The story of ancient Egypt is written not only in the colossal pyramids and the hieroglyphic inscriptions etched upon temple walls but also in the invisible current of belief that flowed through every aspect of its civilization. Religion in ancient Egypt was not a separate institution but a living, breathing force woven into the rhythms of daily life, the rise and fall of the Nile, and the eternal march of the stars across the desert sky.

To understand ancient Egyptian religion is to step into a world where gods walked among mortals, where the sun was reborn each morning after a perilous journey through darkness, and where death was not an ending but a transformation into eternity. Their faith was a tapestry of myth, magic, ritual, and devotion—an intricate system that endured for over three thousand years and left behind some of the most iconic monuments on Earth.

The Divine Landscape of Egypt

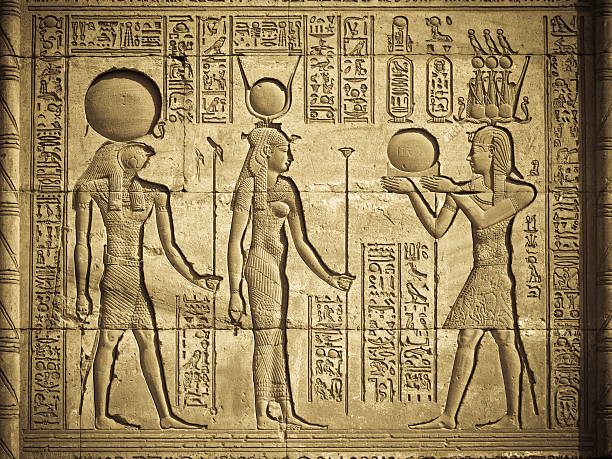

Egypt’s natural environment shaped its religion as much as its culture. The Nile River, the lifeblood of the land, was more than just water; it was a divine gift, flowing with the tears of the goddess Isis and controlled by gods like Hapy, the personification of the annual flood. The blazing sun was Ra, the supreme solar deity, riding across the heavens in his boat. The endless desert beyond the fertile valley represented chaos, danger, and the realm of hostile gods.

For the Egyptians, the landscape was alive with divine presence. Mountains were thrones of gods, the sky was the body of the goddess Nut, and the earth was the god Geb lying beneath her. Even time itself was divine, cycling endlessly in patterns of birth, death, and rebirth.

Gods of Infinite Forms

The Egyptian pantheon was vast and fluid, with gods often merging, evolving, or taking on multiple forms. At the heart of this divine hierarchy were some of the most enduring deities in human history.

Ra: The Sun God

Ra, depicted with a falcon’s head crowned by the solar disk, was the ruler of the heavens and the symbol of eternal light. Each day, he sailed his barque across the sky, bringing life and order. Each night, he descended into the underworld, where he battled the serpent Apophis, embodiment of chaos. His triumph ensured the dawn, and his daily cycle mirrored the eternal struggle between order (maat) and disorder (isfet).

Osiris: Lord of the Afterlife

Osiris was the god of resurrection and judge of the dead. His myth told of betrayal and triumph: murdered by his jealous brother Seth, reassembled and revived by his faithful wife Isis, and enthroned as king of the underworld. Osiris embodied hope—the assurance that life continued beyond death, and that justice awaited in the hall of judgment.

Isis: The Great Mother

Isis was more than Osiris’s consort; she was the goddess of magic, motherhood, and compassion. She was revered for her devotion, using her powers to resurrect Osiris and protect their son Horus. Her worship spread far beyond Egypt, into the Greco-Roman world, where she became one of the most beloved deities of antiquity.

Horus: The Sky and the Pharaoh

The falcon-headed Horus was the child of Isis and Osiris, and the divine symbol of kingship. His battles with Seth represented the triumph of rightful order over chaos. Every pharaoh was considered the living Horus, ruling as the earthly representative of divine authority.

Hathor: Lady of Joy and Love

Hathor, often depicted as a cow or as a woman crowned with horns and the solar disk, embodied love, music, beauty, and fertility. She was the protector of women and mothers, as well as a goddess of the afterlife who welcomed the dead with comfort.

Anubis: Guardian of the Dead

With the head of a jackal, Anubis presided over embalming and guided souls to the afterlife. He weighed the heart of the deceased against the feather of maat. If the heart was pure, the soul was admitted to the eternal fields; if not, it was devoured by Ammit, the monster with crocodile jaws and lion claws.

A Pantheon of Thousands

Beyond these central figures, countless other gods shaped Egyptian life. Thoth, the ibis-headed god of wisdom, was scribe of the gods. Sekhmet, the lion-headed goddess, embodied war and healing. Sobek, the crocodile god, protected the Nile’s waters. The Egyptians’ devotion was not rigid monotheism or polytheism as we know it but a dynamic faith where gods could overlap, fuse, and manifest in countless ways.

The Principle of Maat

At the core of Egyptian religion lay the concept of maat, a word that encompassed truth, justice, balance, and cosmic order. Maat was both a goddess and a principle, the foundation upon which the universe rested. Pharaohs ruled as guardians of maat, ensuring harmony between gods, people, and nature.

Every ritual, every prayer, every offering was an act of reaffirming maat against the constant threat of isfet, chaos. The daily rising of the sun, the regular flooding of the Nile, and the justice of rulers were all expressions of this eternal balance.

Temples: Houses of the Gods

Egyptian temples were not merely places of worship but the very homes of the gods on earth. Colossal in scale and rich in symbolism, they embodied the connection between heaven and earth.

The temple complex of Karnak, dedicated to Amun, was among the largest religious structures ever built, a sprawling city of stone filled with towering pylons, vast courtyards, and sacred lakes. Each temple was a microcosm of the universe: the outer walls symbolized the primordial waters of creation, the hypostyle hall represented the marshes of early earth, and the innermost sanctuary, the naos, housed the god’s statue—a physical embodiment of divine presence.

Temples were not open to the general population. They were sacred spaces where priests conducted daily rituals on behalf of the people. The god’s statue was awakened each morning, bathed, clothed, and offered food, drink, and incense. This ritual sustained the god, who in turn sustained the world.

Priests and Sacred Duties

Priests in ancient Egypt were intermediaries between humans and gods. Their primary responsibility was to maintain the gods’ favor through daily rituals. Unlike modern clergy, Egyptian priests were not lifelong servants of the temple; many rotated in and out of service, spending part of their time as priests and the rest as ordinary citizens.

Purity was central to their role. Priests shaved their bodies, bathed several times daily, and adhered to strict dietary restrictions. Ritual precision mattered above all; a mistake could disrupt maat and endanger cosmic balance.

High priests held immense political and religious authority. In some periods, especially during the New Kingdom, the High Priest of Amun wielded power rivaling that of the pharaoh himself.

Rituals of Life and Death

Religion touched every moment of Egyptian existence, from birth to death.

Daily Rituals

In homes, ordinary Egyptians left offerings to household gods and protective spirits. Amulets depicting deities were worn for health, fertility, or protection. Festivals, filled with music, dancing, and processions, brought the gods out of their temples and into the streets, allowing ordinary people to connect with the divine.

Funerary Beliefs

Death, far from being feared, was seen as a passage into a new phase of existence. The rituals surrounding death were elaborate, designed to ensure safe passage into the afterlife.

Mummification was central to this process. The body, carefully preserved, provided a home for the soul. The ka (life force) and the ba (individual personality) needed the body to recognize and reunite with it. The heart, believed to be the seat of thought and morality, was left in place, for it would be weighed in the judgment hall.

Tombs were decorated with spells, prayers, and scenes of daily life, providing the deceased with all they would need in eternity. The famous Book of the Dead contained instructions and magical incantations to guide the soul safely through the dangers of the underworld.

The Journey to the Afterlife

The soul’s journey was perilous. It traversed the Duat, the underworld, facing demons, gates, and trials. At last, it reached the Hall of Two Truths, where Anubis weighed the heart against the feather of maat. Thoth recorded the result, while Osiris presided over the judgment.

If successful, the soul entered the Field of Reeds, a paradise mirroring Egypt itself, where the blessed dead lived forever in abundance.

Festivals of the Gods

Festivals were moments when religion came alive in public celebration. They brought together priesthood and people, weaving community with divine presence.

One of the most famous was the Opet Festival in Thebes, where the statues of Amun, Mut, and Khonsu were carried in procession from Karnak to Luxor. These journeys symbolized renewal, fertility, and the reaffirmation of the pharaoh’s divine legitimacy.

The Beautiful Festival of the Valley honored the dead, as families gathered at tombs to feast and commune with their ancestors. These festivals blurred the boundaries between the living and the dead, the human and the divine.

Magic and Religion

In Egypt, religion and magic were inseparable. Known as heka, magic was not seen as superstition but as a natural force, a divine power used by gods and humans alike.

Spells, amulets, and charms protected individuals from illness, misfortune, and evil spirits. Physicians used magical incantations alongside medical treatments. Priests invoked heka during rituals to activate the power of offerings and prayers. Even the gods themselves were believed to use magic—Isis, in particular, was celebrated as mistress of magical arts.

Pharaoh: The Divine King

No figure embodied religion more fully than the pharaoh. The king was not just a political leader but a divine being, the living Horus and the son of Ra. His role was to maintain maat, protect Egypt from chaos, and ensure prosperity through ritual and governance.

Pharaohs built temples to honor gods and themselves. Mortuary temples like those of Hatshepsut or Ramses II were not only tomb complexes but also centers of ongoing worship, where the king’s divine essence continued to receive offerings.

Even in death, pharaohs remained divine. The pyramids of the Old Kingdom were not mere tombs but cosmic machines, designed to launch the king’s soul into the heavens to join the imperishable stars.

Continuity and Change in Egyptian Religion

For over three millennia, Egyptian religion displayed remarkable continuity. Yet it was not static. Local gods rose and fell in prominence, often merging with others. Amun of Thebes, once a minor deity, rose to supreme status during the New Kingdom, fused with Ra as Amun-Ra.

There were also radical moments of change, most famously under Akhenaten, who attempted to replace the traditional pantheon with worship of the Aten, the sun disk. This experiment in near-monotheism disrupted the religious order, but after his death, traditional worship returned with renewed vigor.

Legacy of Egyptian Religion

Though the temples fell silent with the rise of Christianity and Islam, the legacy of Egyptian religion endures. Its myths influenced Greek and Roman thought. The cult of Isis spread across the Mediterranean, rivaling Christianity in its early centuries. Even today, Egyptian gods inspire art, literature, and spiritual traditions worldwide.

More profoundly, Egyptian religion bequeathed to humanity a vision of eternity. Their meticulous rituals, grand temples, and timeless myths reveal a people who sought not only to honor the gods but also to make sense of existence itself. They asked the same questions we ask today: What happens after death? What is justice? How do we live in harmony with the universe?

Conclusion: A World Between Heaven and Earth

Ancient Egyptian religion was not a frozen relic of the past but a living, evolving force that shaped one of the greatest civilizations in human history. Its gods embodied nature’s powers, its temples mirrored the cosmos, its rituals sustained both divine and mortal worlds, and its myths offered meaning in the face of mortality.

To walk among the ruins of Karnak or gaze upon the golden mask of Tutankhamun is to feel the lingering presence of this faith. It is to glimpse a worldview where life and death, gods and humans, order and chaos, were bound together in eternal cycles.

The religion of ancient Egypt reminds us that faith is not only about worship but also about wonder—about seeing the universe as alive, meaningful, and filled with the possibility of eternity. It was, in the deepest sense, a religion of life.