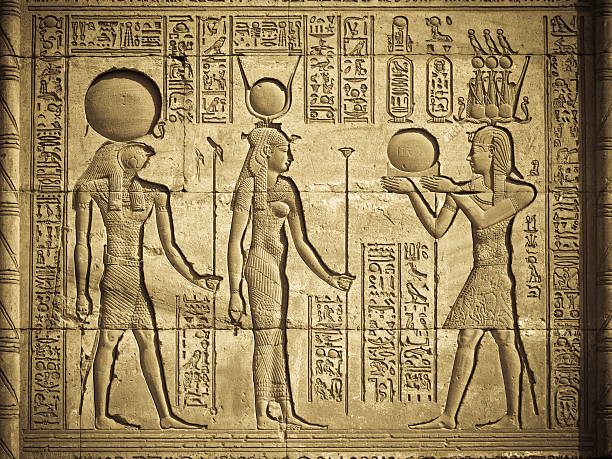

Few legacies from the ancient world ignite as much wonder and fascination as the Egyptian hieroglyphs. These symbols—delicate, intricate, and deeply mysterious—adorned the temples, tombs, and monuments of a civilization that flourished along the Nile for over three millennia. To gaze upon them is to stare into the heart of a culture that viewed writing not merely as a tool of communication, but as something sacred, powerful, and divine. The Egyptians themselves called hieroglyphs “mdw nṯr”—the “words of the gods.”

For centuries, the meaning of these beautiful signs remained an impenetrable riddle. They became silent witnesses to a lost world, admired for their artistry yet shrouded in mystery. It was not until the modern age that scholars, through perseverance and brilliance, managed to crack the code of hieroglyphs, reopening a gateway into the mind of ancient Egypt. To understand hieroglyphs is to listen again to voices silenced for thousands of years.

Origins of the Sacred Script

The story of Egyptian hieroglyphs begins around 3200 BCE, in the shadow of the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaohs. While writing systems developed independently in Mesopotamia, the Nile Valley produced its own unique form—hieroglyphs. Unlike the wedge-shaped cuneiform of Sumer, Egyptian writing favored imagery. A falcon, a reed, an eye, a scarab beetle—each symbol was drawn with exquisite precision, reflecting both the natural world and divine associations.

At first, writing was used for administration: recording taxes, trade, and offerings to temples. But very quickly, hieroglyphs transcended mere practicality. They became woven into Egypt’s worldview, where words were not passive symbols but active forces. To write a name was to ensure immortality. To inscribe prayers upon a tomb was to give voice to the deceased in the afterlife. Hieroglyphs were never simply “letters”; they were vessels of magic, religion, and eternity.

The Sacred Aesthetic

One of the most striking features of hieroglyphs is their beauty. The Egyptians did not see writing as a mechanical process but as an art form. Scribes trained for years to master the precise brush strokes needed to render each sign. The hieroglyphs were often carved into stone with stunning clarity or painted in vivid colors on papyrus and walls.

Hieroglyphic inscriptions could be read in rows or columns, running from left to right or right to left, depending on the direction in which the characters faced. This flexibility added a dynamic quality to the script, almost as though the signs themselves were alive, shifting their gaze. When inscribed in temples or tombs, hieroglyphs were often arranged with symmetry and balance, reflecting the Egyptian devotion to ma’at—the principle of order and harmony that governed the universe.

How Hieroglyphs Worked

To the untrained eye, hieroglyphs appear as pure pictograms—pictures representing ideas. In truth, the system was far more complex. Egyptian hieroglyphs combined three types of signs:

- Logograms, where a single sign represented a whole word. For example, an image of the sun could stand for the word “Ra” or “day.”

- Phonograms, where signs represented sounds, much like letters in an alphabet. A single picture might correspond to one consonant or a group of consonants.

- Determinatives, signs placed at the end of words to clarify meaning. A symbol of a man might follow words relating to humans, distinguishing them from similar words about animals or objects.

This mixture made the system richly expressive but also highly sophisticated. A single word might be written with a combination of phonetic signs and determinatives, giving both sound and meaning. Unlike alphabets, which tend toward simplicity, hieroglyphs remained deliberately layered, reflecting a worldview where words were multidimensional.

The Scribes: Keepers of Divine Knowledge

In ancient Egypt, literacy was rare, and the ability to write hieroglyphs was a mark of high status. Scribes formed an elite class, serving the pharaoh, temples, and government. They recorded taxes, kept chronicles of wars, inscribed religious texts, and preserved literature.

To be a scribe was not merely a job but a sacred calling. Training began in childhood, often in temple schools where students learned to copy signs endlessly on shards of pottery or pieces of limestone. The Satire of the Trades, an Egyptian text used to encourage young scribes, declared their profession far superior to any other—better than being a farmer, soldier, or artisan, for the scribe’s pen commanded respect without toil.

Scribes were also viewed as preservers of immortality. “Man decays, his corpse turns to dust,” one ancient text reads, “but the book makes him remembered.” Through writing, the scribe conquered death itself, ensuring that words would echo long after the body had vanished.

Hieroglyphs and Religion

Nowhere was the sacred power of hieroglyphs more evident than in religion. Temples were covered in inscriptions praising the gods and recounting rituals. Tombs bore spells from the Pyramid Texts, Coffin Texts, and later the Book of the Dead—guides for the deceased in navigating the perils of the afterlife.

The Egyptians believed that words carried magical force. To inscribe a prayer was not simply to record it but to activate it. Names were especially potent. To erase someone’s name from a monument was to deny them existence in eternity, a fate worse than death. Conversely, to write a god’s name was to invoke their presence.

This sacred dimension meant that hieroglyphs were not only tools of communication but instruments of divine power. They linked the earthly and the eternal, the human and the divine.

The Decline of Hieroglyphs

For thousands of years, hieroglyphs flourished. But with the conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great in 332 BCE and the rise of the Ptolemaic dynasty, Greek gradually became the language of administration. Later, under Roman rule and the spread of Christianity, hieroglyphs fell into disuse.

By the 4th century CE, the ability to read them had been lost entirely. The last known hieroglyphic inscription, carved in 394 CE at the Temple of Philae, marked the end of a script that had endured for over 3,000 years. Without scribes to interpret them, the sacred signs turned into enigmatic pictures, inspiring awe but concealing their meaning.

For centuries afterward, scholars speculated wildly about their nature. Some believed hieroglyphs were purely symbolic, containing secret mystical wisdom rather than linguistic content. This misunderstanding persisted through the Middle Ages and Renaissance, when hieroglyphs were admired as esoteric symbols but not truly understood.

The Rosetta Stone: A Key from the Past

The great breakthrough came unexpectedly in 1799, when French soldiers in Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign discovered a black basalt slab near the town of Rosetta. This stone bore an inscription in three scripts: Greek, Demotic (a later Egyptian script), and hieroglyphs.

Because Greek was known, scholars realized they held a parallel text. If the inscriptions matched, the Greek could provide a key to unlocking the hieroglyphs. The Rosetta Stone became the single most important artifact in the history of Egyptology.

For years, scholars across Europe attempted to decipher the script. Progress was slow, and rivalries fierce. But eventually, in the early 19th century, two men emerged at the center of the race: the English polymath Thomas Young and the French scholar Jean-François Champollion.

Champollion and the Decipherment

While Young made early advances, it was Champollion who ultimately cracked the code. Building on years of study, he realized that hieroglyphs were not purely symbolic, as many had thought, but a complex system combining phonetic and logographic signs.

In 1822, Champollion announced his breakthrough: by comparing Greek names like “Ptolemy” and “Cleopatra” with their hieroglyphic counterparts, he identified the phonetic values of certain signs. From there, he expanded the system, proving that hieroglyphs represented a full written language.

When he triumphantly shouted, “Je tiens l’affaire!” (“I’ve got it!”), he had not only solved a linguistic puzzle but opened an entire civilization to the modern world. For the first time in over a thousand years, the words of the pharaohs could be heard again.

Rediscovering Egyptian Voices

With the decipherment of hieroglyphs, ancient Egypt came alive in ways never before possible. Inscriptions on tombs revealed personal prayers, hymns to the gods, and tales of daily life. Administrative records described harvests, labor, and taxes. Royal decrees proclaimed victories in battle and acts of devotion to the gods.

Literature, too, emerged from the shadows: love poems, wisdom texts, fables, and epic tales. The Egyptians, once silent figures in stone, now spoke with warmth, wit, and humanity. They joked, they lamented, they dreamed of eternity. Hieroglyphs allowed modern readers to meet them not as distant idols but as real people.

Hieroglyphs in Modern Culture

Today, Egyptian hieroglyphs are instantly recognizable around the world. They appear in films, video games, jewelry, tattoos, and fashion. They symbolize mystery, ancient wisdom, and a timeless connection to humanity’s past.

Yet this fascination sometimes leads to misunderstandings. Pop culture often portrays hieroglyphs as magical codes or alien messages. In reality, they were a living language, used daily by scribes, priests, and officials. Their true power lies not in fantasy but in their authenticity—an ancient people’s effort to preserve memory, identity, and belief.

The Legacy of the Gods’ Language

Egyptian hieroglyphs are more than relics of a dead language. They are a bridge across time, linking us to one of the most extraordinary civilizations in human history. They remind us that writing is not merely a practical invention but a cultural achievement, one that can embody art, religion, and philosophy.

By decoding hieroglyphs, we did not merely solve a puzzle; we restored voices that had been silenced for centuries. We rediscovered the prayers of kings, the wisdom of scribes, the hopes of farmers, and the love songs of ordinary men and women.

Hieroglyphs endure as testimony to the human drive for expression, memory, and immortality. They are proof that words can outlast empires, that symbols carved in stone can echo across millennia, and that the language of the gods still speaks to us, if we take the time to listen.