To imagine daily life in ancient Egypt is to step into a world where the rhythms of existence pulsed with the flooding of the Nile, where gods were believed to walk beside men, and where the weight of eternity shaped even the most ordinary tasks. For thousands of years, Egypt flourished as one of the most enduring civilizations in human history. Yet the story of its people—their meals, their laughter, their work, and their dreams—comes not from written chronicles alone but from what they left behind in their tombs, villages, and discarded fragments of daily use.

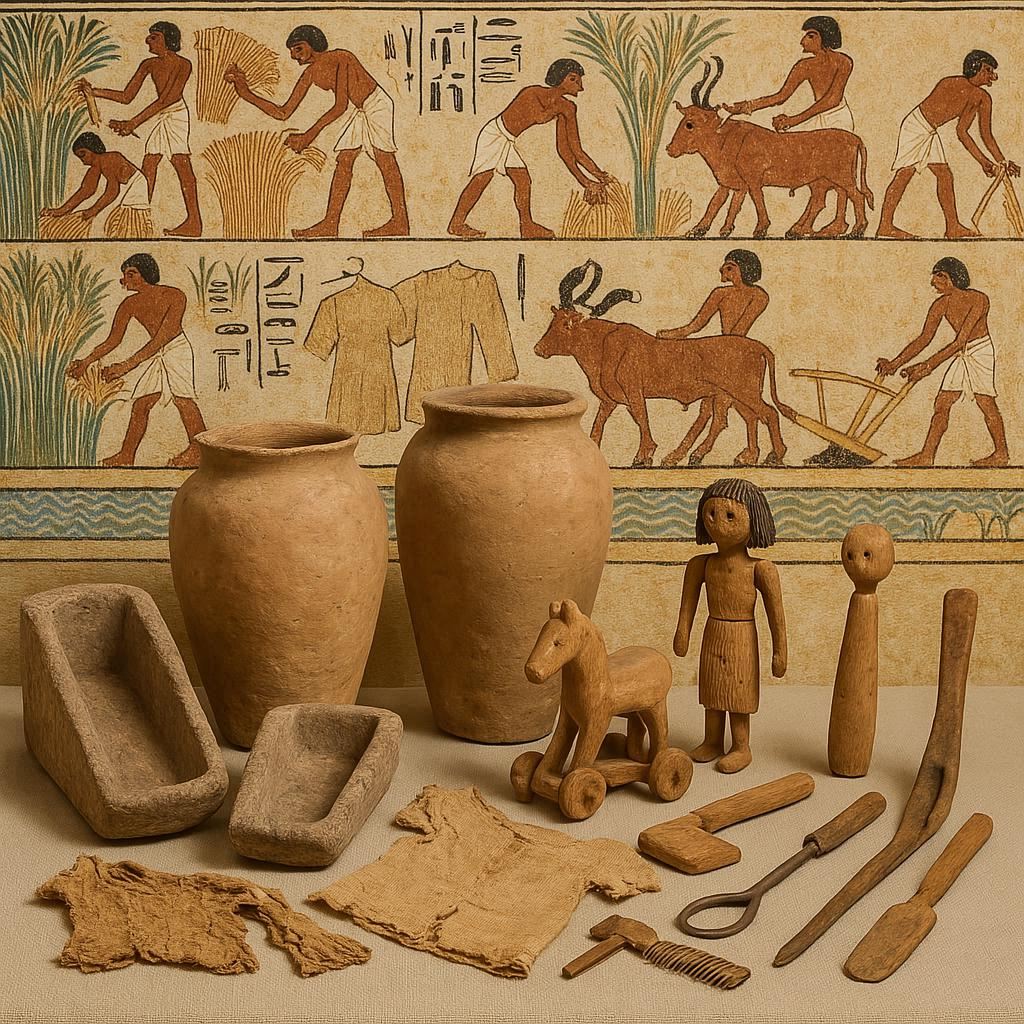

Archaeological finds—pottery, tools, graffiti, bread molds, children’s toys, even desiccated remains of food—paint a vivid portrait of how ordinary Egyptians lived. From the bustling markets of Memphis to the quiet village of Deir el-Medina, from the grandeur of palaces to the humbler mudbrick homes, archaeology allows us to reconstruct not only the grandeur of kings but the pulse of everyday life. These discoveries remind us that the people of ancient Egypt were not merely shadowy figures of myth and monument, but living, breathing individuals who loved, labored, feasted, quarreled, and hoped much as we do today.

The Landscape That Shaped Life

Daily life in ancient Egypt cannot be separated from its geography. The Nile was the country’s lifeblood, flooding annually to deposit rich silt along its banks. This dependable rhythm dictated agricultural cycles, work schedules, and even festivals. Farmers sowed when the waters receded, reaped when the crops matured, and stored grain against the uncertainties of the next year. Archaeological remains of granaries, silos, and irrigation canals illustrate how central farming was to survival.

Villages were often constructed close to fertile land, built with mudbrick that has long since eroded yet left traces in foundations and collapsed walls. Excavations reveal that homes were modest: small rooms with flat roofs, often used as storage or sleeping areas during hot nights. The contrast between the simple architecture of peasants and the monumental stone temples or tombs of the elite underscores the divide between ordinary and extraordinary, but both were bound together by the same Nile and the same cycles of time.

Food on the Table

Archaeological evidence reveals much about Egyptian cuisine, which was simple yet nourishing. Bread and beer formed the staples, so omnipresent that they became symbols of life itself. Archaeologists at Amarna and other sites have uncovered thousands of bread molds, beer jars, and grinding stones. Bread was coarse, often mixed with sand or grit from grinding, which left telltale wear on the teeth of mummies. Beer was thick, porridge-like, and consumed daily by rich and poor alike.

Beyond these staples, vegetables such as onions, garlic, leeks, and lentils were common, as shown by preserved remains found in tombs. Fruits like dates, figs, and pomegranates sweetened the diet, while honey, highly prized, was the main sweetener. Meat was less common for peasants, though wealthier households enjoyed beef, duck, or goose, while fish from the Nile filled in the gap for many.

In the tomb of Kha and Merit at Deir el-Medina, archaeologists found preserved loaves of bread, jars of honey, and even cuts of meat, left as offerings for the afterlife. These finds offer direct glimpses into the meals Egyptians hoped to enjoy eternally, echoing the dishes they ate in daily life.

Clothing and Adornment

What did Egyptians wear as they went about their days? Linen, spun from flax, was the fabric of choice, as revealed by countless textile fragments and depictions on tomb walls. For ordinary people, garments were simple tunics or kilts, often plain and practical for the heat. Wealthier Egyptians wore more elaborate, finely woven linen, sometimes bleached white or pleated for style.

Jewelry, however, transcended social classes. Excavations have uncovered beads made of faience—a bright blue-green glazed ceramic—as well as amulets worn for both beauty and protection. Gold and semi-precious stones adorned the wealthy, while humbler materials sufficed for common folk. These artifacts reveal that Egyptians, like us, took pride in appearance and believed adornment could influence fate.

Homes and Domestic Life

Archaeological sites such as Deir el-Medina provide a rare window into the domestic life of artisans and laborers. Their homes, preserved in part by desert sands, were small but functional, with rooms for sleeping, storage, and cooking. Hearths, ovens, and grinding stones discovered in these houses show how meals were prepared.

Wall graffiti and ostraca (pottery shards with writing) found in the village tell us that family life was lively, filled with both affection and tension. Some ostraca preserve school exercises or household accounts, while others contain personal notes, complaints, or even jokes. This everyday writing gives us voices of the ordinary people of Egypt—voices that often slip through the cracks of history.

Children’s toys found in excavations—dolls, carved animals, and gaming boards—remind us that even in a land of gods and pharaohs, childhood was marked by play and imagination. These finds humanize the past, showing us not just how people worked but how they found joy.

Work and Occupations

Daily life in Egypt was structured by labor. The majority of people were farmers, tied to the rhythms of planting and harvest. Tools such as sickles with flint blades, hoes, and plows, preserved in graves and settlements, illustrate the toil of the fields.

Craftsmen formed another crucial part of society. Excavations have yielded pottery kilns, weaving looms, carpentry tools, and evidence of metalworking. These artisans produced not only practical goods but also objects of beauty for temples, tombs, and homes.

The workers at Deir el-Medina—tasked with constructing the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings—leave us some of the richest records of labor life. Ostraca and papyri from the site document strikes over unpaid wages, quarrels between neighbors, and meticulous accounts of work shifts. This evidence paints a vivid picture: even in ancient Egypt, workers sought fairness and community.

Women also played vital roles. Though the public sphere was dominated by men, archaeological finds show women as bakers, weavers, priestesses, and even business owners. Grave goods and inscriptions suggest women held more legal and social rights than in many other ancient societies.

Religion and Ritual in Daily Life

Religion permeated every corner of Egyptian existence. Archaeological finds—amulets, household shrines, ritual figurines—demonstrate that devotion was not limited to grand temples. Ordinary families prayed to household gods like Bes, protector of children, or Taweret, goddess of childbirth.

Offerings of food, incense, and figurines found in domestic contexts show how spirituality was woven into daily routines. Tomb paintings depict not only grand rituals but also humble acts of devotion, underscoring the belief that divine forces shaped both the mundane and the eternal.

The sheer number of religious artifacts unearthed—scarabs, statues, inscribed stelae—speaks to a worldview where the sacred and the everyday were inseparable.

Education and Writing

Archaeology has also illuminated education in Egypt. Ostraca and papyri found in village dumps and tombs preserve school exercises—lists of words, moral lessons, or copies of classic texts. These finds show how literacy was passed on, primarily to boys training as scribes.

Scribes held high status, for writing was power. They recorded harvests, wrote letters, drafted contracts, and preserved sacred hymns. The discovery of personal letters, written on papyrus or pottery shards, gives us glimpses of daily communication—requests for supplies, notes of gratitude, even complaints to officials.

Writing in Egypt was not merely practical; it was an art, a sacred gift of Thoth, the god of wisdom. Every hieroglyph carved in stone or written on papyrus reflects both functional and spiritual dimensions of literacy.

Leisure and Entertainment

Despite the labor and ritual, Egyptians also found time for leisure. Archaeological finds reveal gaming boards for senet and mehen, played by rich and poor alike. Senet boards, discovered in both humble homes and royal tombs, were thought to be not only entertainment but also symbolic of the journey to the afterlife.

Music and dance were also part of daily life. Instruments—harps, flutes, tambourines—have been found in tombs and settlements, suggesting that music accompanied both work and celebration. Figurines depicting dancers and musicians highlight how deeply performance was woven into culture.

Banquets, depicted in tomb art and confirmed by remains of pottery, beer jars, and food offerings, show that Egyptians celebrated with feasts, music, and wine. These moments of joy balanced the hardships of life, just as they do for us.

Health, Medicine, and Healing

Archaeological finds provide evidence of both disease and healing. Mummified remains show signs of arthritis, dental decay, and parasitic infections. Yet they also reveal medical interventions: splints for broken bones, trepanned skulls, and evidence of surgical attempts.

Papyri such as the Ebers Papyrus, supported by finds of medical tools, show a blend of practical medicine and magical incantations. Healing involved both herbs and prayers, with physicians seen as mediators between human suffering and divine intervention.

The remains of cosmetics—kohl eyeliner, scented oils—were not only for beauty but also had protective and medicinal purposes, shielding eyes from infection and skin from the sun. These artifacts remind us that health was pursued with both science and spirit.

Death and the Afterlife in Daily Context

Perhaps the most famous archaeological finds from Egypt are tombs, mummies, and funerary goods. These reveal not only beliefs about death but also reflections of daily life. Tombs were stocked with food, furniture, tools, clothing, and even board games—the necessities of life, intended to be used forever.

The discovery of household items in burials underscores how the boundary between daily existence and eternity was blurred. Death was not an end but a continuation, and the goods of the living world were carried into the next.

Even the humblest graves, with simple pottery or bread offerings, reflect a belief in continuity of daily life beyond death. This emphasis makes Egypt’s archaeology uniquely rich in its depiction of the ordinary as eternal.

Archaeology as Storytelling

Every pot shard, every bead, every scrap of papyrus is a fragment of a larger story. Archaeologists, piecing together these fragments, reconstruct the tapestry of ancient Egyptian life. Excavations at Amarna reveal urban planning, household layouts, and even discarded fish bones, offering a slice of city life. The tombs of Deir el-Medina artisans preserve not only tools and art but also the emotions of those who created the resting places of kings.

Through these finds, we are reminded that history is not abstract—it is human. The daily lives of ancient Egyptians were filled with the same mixture of labor and laughter, hardship and joy, that characterize our own.

Conclusion: Eternal Echoes of Ordinary Lives

Daily life in ancient Egypt, revealed through archaeology, is not only a tale of monuments and mummies but of people. Farmers bent over fields, mothers tending children, scribes carefully copying texts, children playing with dolls—these scenes, recovered from the dust, speak across millennia.

The artifacts whisper of a people deeply rooted in their land and faith, yet also practical, playful, and profoundly human. Archaeology transforms the distant and monumental into the intimate and relatable.

In the worn grinding stones, we hear the sound of bread being prepared. In the faded graffiti, we sense the humor of workers. In the preserved loaves of bread and jars of beer, we see hopes for eternity that mirror daily reality. Ancient Egypt, in all its grandeur, was also a place of kitchens and workshops, of lullabies and laughter, of human lives lived in full.

The ruins and relics are not silent; they are voices of the past, reminding us that the story of Egypt is not just about kings and gods but about the eternal dignity of ordinary life.