In a remarkable blend of archaeology and forensic science, a recent study led by Ph.D. candidate Leonie Hoff of the University of Oxford has peeled back the layers of time to reveal intimate details about the artisans behind ancient Egyptian terracotta figurines. Published in the Oxford Journal of Archaeology, Hoff’s research showcases how fingerprints—some over two thousand years old—can divulge the age and sex of those who shaped clay into divine and domestic forms.

The study draws from figurines excavated at the submerged city of Thonis-Heracleion, an ancient Egyptian port now submerged beneath the Mediterranean Sea. By harnessing cutting-edge Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI), Hoff analyzed the preserved fingerprints on these figurines and unearthed the subtle but telling ridge patterns left behind by their creators. The results are both intriguing and revolutionary, offering a vivid glimpse into the labor and lives of ordinary artisans in the ancient world.

Rediscovering Thonis-Heracleion

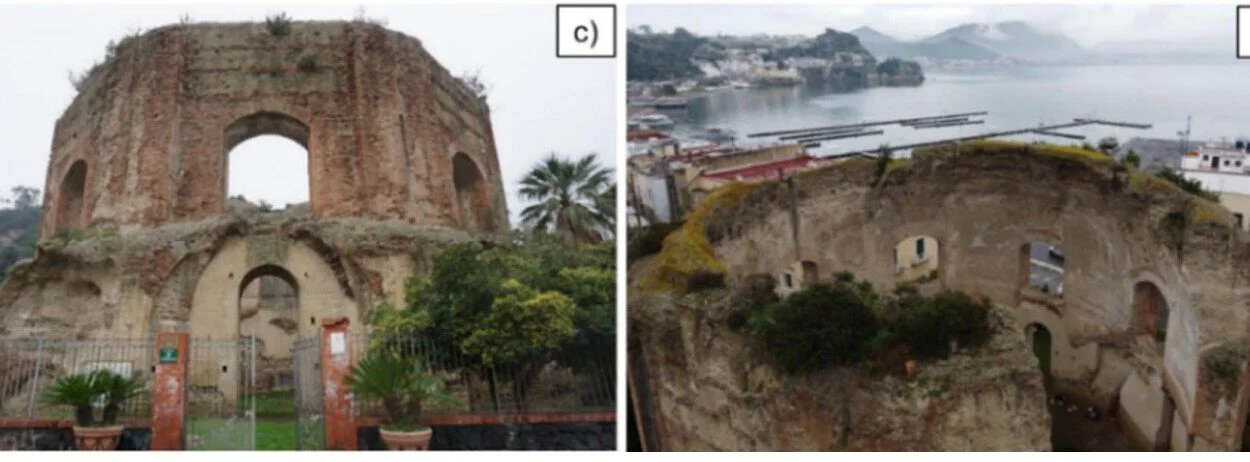

Founded in the eighth century BC and flourishing during Egypt’s Saite and Ptolemaic periods, Thonis-Heracleion once stood as a bustling hub of commerce and culture. Strategically situated at the Canopic mouth of the Nile, the city was a gateway to the Mediterranean, overseeing trade, immigration, and diplomacy—especially between Egypt and Greece.

For centuries, it thrived until the rise of Alexandria, founded by Alexander the Great, which gradually usurped its role as Egypt’s primary harbor. The city sank beneath the sea sometime in the second century BC, where it remained a watery myth until dramatic underwater excavations in the 1990s brought it back to light. Among the many artifacts recovered were 60 terracotta figurines—nine of which bore clear fingerprint impressions.

Figurines and the Mystery of Their Makers

Terracotta figurines were everyday objects in the ancient world, used for religious rituals, household decoration, and as toys. But despite their ubiquity, little has been known about the people who made them. Traditionally, Egyptian figurines were crafted from Nile silt—a coarse, muddy material that limited fine detail. However, as techniques evolved and Hellenistic influence spread, craftsmen began using refined clays to produce more intricate and stylistically Greek forms.

One clue about these artisans comes from language. In ancient Greek, the word koroplathos—meaning “doll or boy molder”—was a masculine term. This led many scholars to presume figurine-making was an exclusively male profession, at least in the Greek world. But the gender of artisans in Egypt remained an open question, and written records offer few answers. Hoff’s study, however, now provides fresh, physical evidence.

Fingerprints as Ancient Signatures

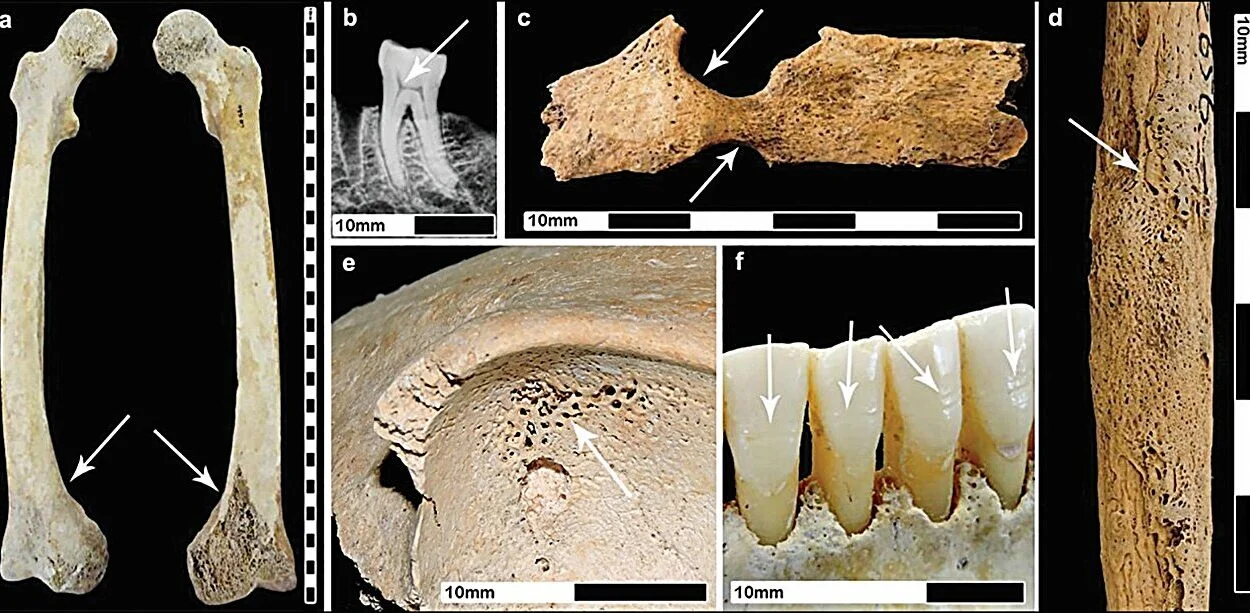

The figurine-making process left behind subtle but persistent clues. Wet clay was pressed into molds, dried partially, and then the halves were joined to form a complete figure. In doing so, artisans often left their fingerprints, invisible to the eye but recoverable with modern technology.

Hoff applied RTI imaging—a technique that uses angled light to reveal surface topography in high detail—and performed a forensic analysis known as ridge density analysis. This method measures how many epidermal ridges appear within a given area. Statistically, female fingerprints have higher ridge density, while male prints are less dense. She compared these ancient fingerprints to modern Egyptian population data to draw her conclusions.

To determine age, she measured ridge breadth. Children have narrower ridges, while adults’ ridges are wider. From this, she was able to identify whether a fingerprint belonged to a child, adolescent, or adult, and—where applicable—assign a probable sex.

The Artisans Behind the Clay

The results were striking. At least 14 different individuals had worked on the figurines—both males and females. Contrary to the long-held assumption that figurine-making was a male-only trade, the fingerprints revealed a nearly equal distribution of men and women involved in the process. Interestingly, female participation was slightly higher in the creation of local Egyptian figurines compared to those influenced by Greek imports.

Even more fascinating was the evidence of children involved in production. Their fingerprints—smaller, with thinner ridge breadths—appeared only on the interior surfaces of figurines, suggesting their involvement in pressing clay into molds. Adult fingerprints, in contrast, were found both inside and outside the figurines, especially near the bases, where the mold halves were joined.

This pattern implies a production chain: children performed preparatory work, likely under the watchful eye of an adult supervisor who finalized the piece. Hoff noted that children’s fingerprints never appeared alone, indicating they did not work independently. This collaborative process mirrors cross-cultural ethnographic patterns observed in traditional potteries, where children are gradually introduced to craft under adult mentorship.

Cultural Differences in Apprenticeship

Beyond the demographic revelations, Hoff’s study unveiled subtle differences in figurine production practices between Egyptian and Greek traditions. Egyptian figurines tended to pair children with slightly older adolescents or young adults—a relatively small age gap that suggests a peer-to-peer learning structure or familial apprenticeship model.

In contrast, Greek figurines often showed signs of adult-child pairs with a much wider age gap, implying a more formalized master-apprentice relationship. These variations hint at differing philosophies of vocational training between the two cultures—one informal and perhaps community- or family-based, the other more hierarchical and structured.

A Silent Archive Comes to Life

What makes this study especially engaging is how it humanizes a class of artisans often lost to history. Hoff has brought ancient fingerprints to life, turning what was once a silent archive of clay into a story of collaboration, gender inclusion, and intergenerational learning.

“For my material, identifying specific individuals is currently not possible,” Hoff explains, “due to the mostly fragmentary state and the fact that the figurines are not from exactly the same date.” But she cites studies on Roman lamps from the Levant where repeated fingerprints have successfully been linked to specific individuals, suggesting that with a more extensive dataset, similar insights might be gleaned from Egyptian material.

Implications for Future Research

The broader implications of this research are profound. Hoff’s work underscores how modern forensic tools can enrich archaeological interpretation. Ancient fingerprints—once regarded as random blemishes—are now understood as critical data points that reveal the identities and relationships of those behind the scenes.

It also challenges assumptions about labor, gender roles, and childhood in the ancient world. Children, far from being passive observers, were active participants in economic life. Women, despite a lack of textual acknowledgment, played a significant role in material production. And craft training was not a monolithic institution but varied by culture and context.

Hoff hopes to continue expanding the research. “For the site I’m working on, the terracotta material is currently quite limited. I’m hoping that we find more terracottas to be able to add more data to the study,” she said. Additional finds could illuminate not only the fingerprints but also the social fingerprints—the networks of family, labor, and training—that sustained ancient Egypt’s artisanal traditions.

A Clay Chronicle of Human Touch

In the end, Hoff’s work is a testament to the enduring power of human touch—literally. Those long-forgotten fingers that pressed, shaped, and sealed humble figurines have reemerged as voices from the past, whispering tales of apprentices and masters, mothers and sons, artists and children.

In a world obsessed with monumental kings and towering pyramids, it is refreshing to see attention paid to the clay-stained hands of everyday life. These fingerprints are more than just impressions in clay—they are impressions in history.

Reference: Leonie Hoff, Fingerprints on figurines from Thonis‐Heracleion, Oxford Journal of Archaeology (2024). DOI: 10.1111/ojoa.12308