For centuries, the ruins of Caracol lay quiet beneath the dense green canopy of Belize’s Maya Mountains. Trees burst through collapsed temples, and vines coiled around broken stones once etched with glory. Time had stolen the voices of this ancient city — until now.

Beneath a royal shrine, archaeologists have unearthed something extraordinary: the tomb of Te K’ab Chaak, the first known ruler of Caracol and the founding father of its royal dynasty — a man who lived and ruled over 1,700 years ago. With this discovery, an ancient silence has been broken, and the soul of a forgotten king has stirred again in the humid heart of Central America.

It is the first identifiable royal burial ever found at Caracol in more than four decades of excavation — a discovery not just of bones and jade, but of origins, ambition, and mystery stretching far beyond Belize’s borders.

A Sleeping King Beneath Stone and Time

The tomb, sealed for nearly two millennia, was discovered at the base of a family shrine in Caracol’s Northeast Acropolis, a ceremonial heart of a city that once pulsed with power, trade, and ritual. Inside, archaeologists found the aged remains of a man estimated to be about 5 feet 7 inches tall, interred without teeth, his body surrounded by riches once meant to accompany him to the afterlife.

Eleven finely crafted pottery vessels lay in the chamber, whispering stories through their painted scenes — one depicting a Maya ruler receiving offerings from divine supplicants, another bearing the fearsome image of Ek Chuah, god of commerce and trade. Four of the vessels bore images of bound captives, a chilling yet customary display of power and dominance. Two others featured modeled coatimundi heads, the animal known as tz’uutz’ in Maya, a symbol later adopted into royal names like a family crest.

Beside him lay carved bone tubes, mosaic jadeite jewelry, Pacific spondylus shells, and traces of organic material — now perished, but once sacred. Most striking of all was a jadeite death mask, still being reconstructed, its pieces once set lovingly over the face of a man whose identity now pulses through stone like heartbeat through bone.

“It’s the tomb of a founder,” said Dr. Arlen F. Chase, who has excavated Caracol with his wife Dr. Diane Z. Chase for more than forty years. “And founders are rare. They often disappear beneath the layers of history. But here he is — still speaking to us.”

A City’s Beginning, A Continent’s Network

Caracol, now a ruin swallowed by rainforest, was once a Maya superpower. From 560 to 680 AD, it was a political and military juggernaut, shaping the fate of the southern Yucatán Peninsula with cunning, conquest, and sheer grandeur. But long before that golden age, its roots were already sinking deep into Mesoamerican soil.

Te K’ab Chaak, who acceded the throne in 331 AD, was not merely the founder of a dynasty — he was a bridge between worlds.

What researchers have uncovered suggests a far more complex story than previously imagined: that Caracol was already engaged in far-reaching cultural and political exchanges with civilizations over 1,200 kilometers away, including the mighty metropolis of Teotihuacan in central Mexico.

A cremation burial, unearthed just meters from Te K’ab Chaak’s tomb and dated to 350 AD, strengthens this astonishing connection.

Flames, Blades, and Foreign Gods

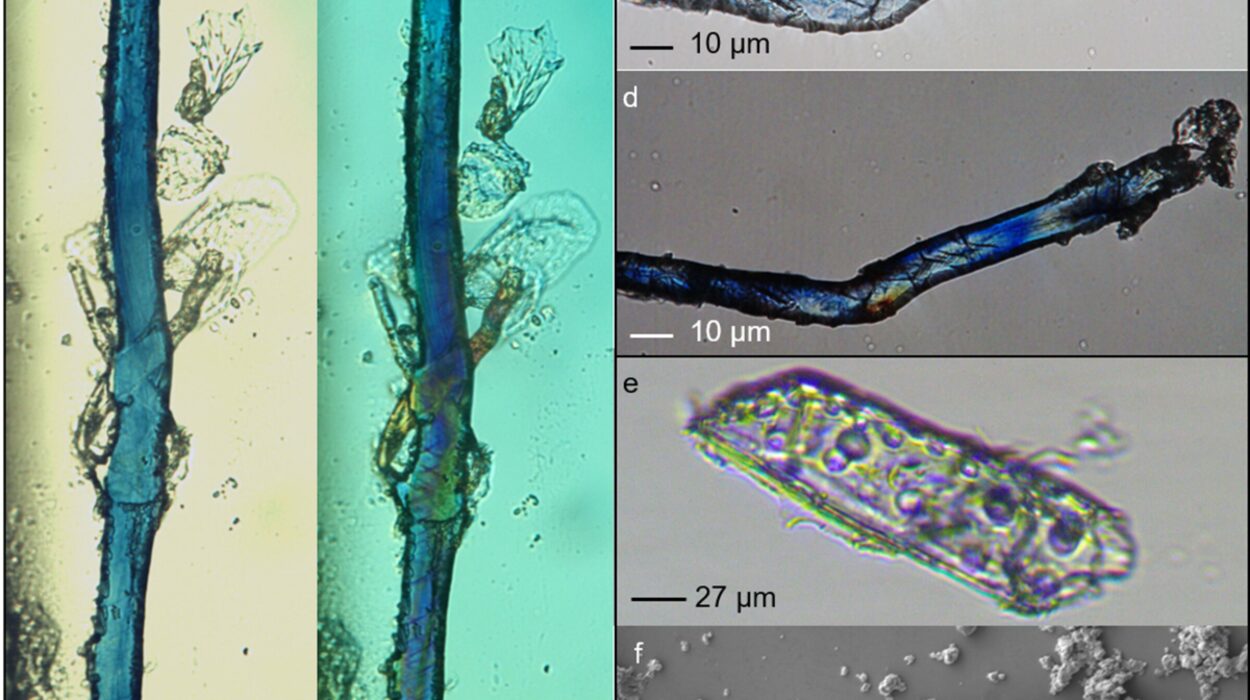

In 2010, archaeologists uncovered a cremation pit at the very center of the Northeast Acropolis plaza. This wasn’t a simple offering or a common grave — it was a ritual cremation of three individuals, most likely elites. Alongside their burned remains were objects that didn’t belong to Maya tradition: two large knives, six atlatl (spear-thrower) points, and fifteen obsidian blades, their brilliant green color betraying their origin — Pachuca, north of Teotihuacan.

Also found was a carved projectile tip, a type of weapon used by Teotihuacan warriors — but alien to the Maya.

The entire cremation and its public plaza location were foreign too. Cremation was rare among the Maya, particularly for royalty. In contrast, Teotihuacan honored its elite dead with fire. The burial’s placement in a residential plaza, the array of imported artifacts, and the fusion of styles suggest this was no ordinary noble: it may have been a Maya elite who lived in Teotihuacan, a royal envoy, or a cultural hybrid raised between worlds.

“These remains show us that rituals from Teotihuacan were already present at Caracol before the historical ‘entrada’ event of 378 AD,” said Dr. Diane Chase. “It rewrites the timeline. The Maya were not isolated. They were part of a Mesoamerican web.”

Before the Entrada, There Was Caracol

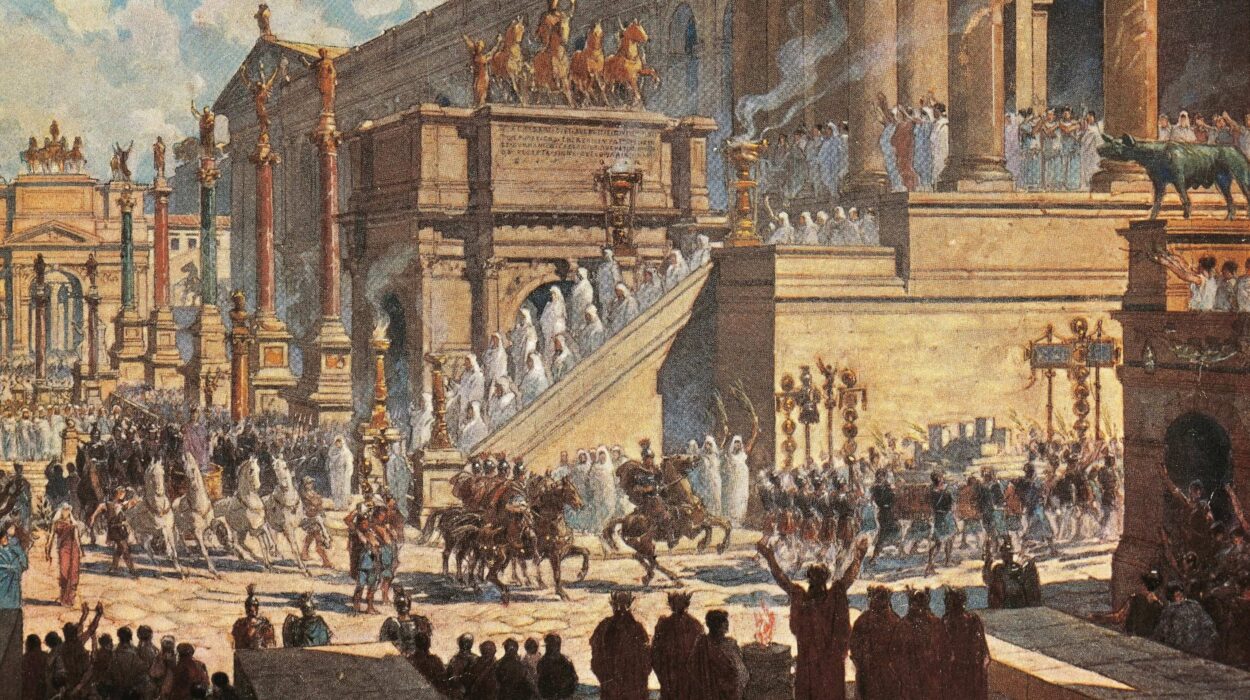

For decades, archaeologists have puzzled over the event known as the “entrada” — a turning point in 378 AD when Teotihuacan’s influence exploded into the Maya lowlands. Monuments and glyphs from cities like Tikal depict the sudden arrival of foreign lords and warriors, reshaping dynasties and culture.

But Caracol’s Northeast Acropolis tells a deeper story — one that pushes back the clock on interregional contact and shatters the myth of Maya isolation.

Alongside Te K’ab Chaak’s tomb and the cremation pit lies a third burial — a woman’s grave uncovered in 2009, rich with hematite, spondylus shells, a mirror, and pottery, all echoing both Maya and central Mexican symbolism. Dated again to around 350 AD, she was part of this triad of power — royal, cosmopolitan, and complex.

“These three tombs form a cluster that predates the entrada by a generation,” said Dr. Arlen Chase. “What we’re seeing is evidence of formal diplomatic relationships, of elite exchange, of ritual knowledge flowing between regions.”

In short: the Maya weren’t simply invaded or influenced. They were participants in a continental dialogue.

Travelers of the Ancient World

Modern maps can deceive us. Today, the journey from Teotihuacan to Caracol takes more than 23 hours by car, through highways, borders, and borders of civilization. In 350 AD, it would have taken over 150 days on foot, across mountains, rivers, and forests.

And yet, these journeys happened. Goods moved. Ideas moved. People moved.

Jade from Guatemala glistened on altars in Tikal. Obsidian from Pachuca spilled across royal tombs in Caracol. Deities, masks, weapons, and names traveled like wind through the tree canopy — unseen but powerful.

Te K’ab Chaak’s tomb — with its fusion of Maya and Teotihuacan symbols — tells us that the New World was not a set of isolated kingdoms, but a living, breathing network of ancient cities connected by ambition, religion, and human drive.

A Legacy Rekindled

Te K’ab Chaak’s dynasty ruled Caracol for more than 460 years, shaping one of the largest and most enduring Maya city-states. Yet until now, his voice was lost to history. This discovery doesn’t just reintroduce us to a man — it opens the curtain on an entire epoch.

Work continues in the chamber where his body was found. Specialists are reconstructing the jade death mask, which may soon reveal the first image of this lost king’s face. DNA analysis, stable isotope studies, and artifact examination will further unravel who he was, where he came from, and how he lived.

The Chases, now in their fifth decade of excavation at Caracol, will present their findings next year at the Santa Fe Institute, at a conference dedicated to Maya–Teotihuacan interaction.

But already, Te K’ab Chaak has done what few kings manage after death — he has returned to the world stage, not with weapons or monuments, but with mystery, wonder, and questions still burning bright.