High in the Himalayas, where oxygen is thin and the cold bites to the bone, humans carved out life long before we ever imagined. Now, a groundbreaking genomic study reveals just how early—and how extraordinary—the story of Himalayan survival truly is.

In the windswept corridors of the Himalayas, survival is not just a daily battle—it is an evolutionary triumph. Towering over the world, these ancient peaks have long been seen as a near-insurmountable barrier. Yet, for thousands of years, people have not only lived but thrived in these punishing altitudes. A new international study now reveals how, using nothing less than the blueprint of life itself.

Published in Current Biology, the research offers the most comprehensive genetic portrait ever assembled of Himalayan peoples—an intricate tapestry woven from ancient migration, natural selection, and stunning adaptations that challenge everything we thought we knew about human endurance.

Led by Dr. Marc Haber of the University of Birmingham Dubai, the team sequenced the whole genomes of multiple ethnic groups across the Himalayan region, many of which had never before been studied at such depth. The result? A revelation that the genetic structure of Himalayan populations began forming over 10,000 years ago—long before archaeologists have found signs of permanent human settlement at these high elevations.

“This study offers an unprecedented window into the genetic legacy of Himalayan populations and their extraordinary adaptations to high-altitude life,” said Dr. Haber. “It reveals how migration, isolation, and natural selection came together to shape human survival in one of the world’s most challenging environments.”

Life on the Edge of Breath: The Genetics of Hypoxia

At altitudes above 4,000 meters, every breath is a struggle. Oxygen levels can drop to nearly half of what they are at sea level, placing immense stress on the body. For most of us, prolonged exposure at such heights leads to altitude sickness. But for many Himalayan peoples, this is simply where life begins.

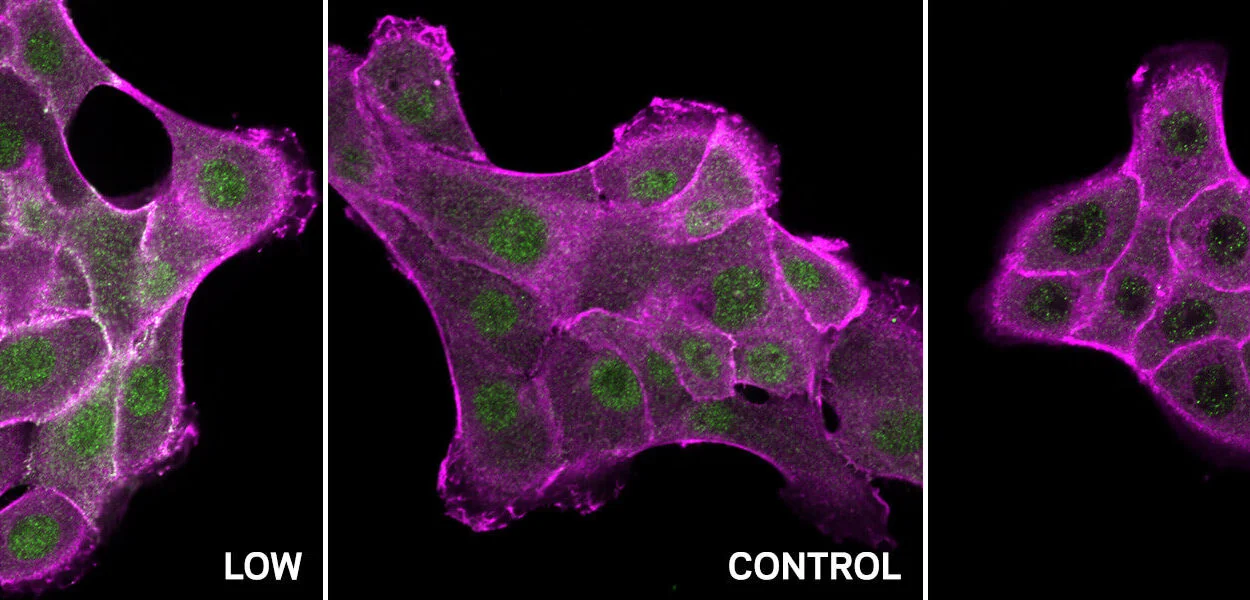

The new study identified novel gene variants associated with the body’s ability to handle low-oxygen environments, also known as hypoxia. Among them is a genetic superstar: EPAS1, a gene originally inherited from Denisovans—an extinct, mysterious cousin of modern humans who interbred with our ancestors tens of thousands of years ago.

This gene, often called the “super athlete gene,” regulates hemoglobin production and oxygen processing. It enables Tibetan and other Himalayan populations to maintain normal oxygen levels in their blood without thickening it—a key factor in long-term high-altitude survival.

“EPAS1 has been studied before in Tibetan populations,” explained Dr. Mohamad Almarri, co-first author from Mohammed Bin Rashid University of Medicine and Health Sciences in Dubai. “But what’s remarkable is how widespread this and other Denisovan-derived variants are across diverse Himalayan groups.”

Even more surprisingly, the study found that certain genetic variants—previously associated with the incredible breath-hold diving abilities of Southeast Asian Bajau people—were also present in some lowland Himalayan populations. This suggests an unexpected evolutionary link between groups separated by geography, but perhaps united by shared physiological challenges.

Islands in the Sky: Isolation and Migration Intertwined

Despite the towering, rugged geography that isolates many Himalayan communities, the researchers discovered evidence of bidirectional gene flow—genetic mixing both into and out of the region—with Central and South Asia as well as East Asia.

These migrations were not random. They corresponded with the rise and expansion of major historical powers like the Tibetan Empire and Gupta Empire, when trade, conquest, and cultural exchange brought distant peoples together. Even so, many Himalayan populations remained relatively genetically distinct—like islands in the sky, evolving unique adaptations over thousands of years.

“The Himalayas are often seen as a barrier to movement,” said Dr. Almarri, “but our genetic data reveal a dynamic history of both isolation and migration. By sequencing these diverse populations, many for the first time, we uncovered how people in this region are related to one another and to their neighbors.”

Genes of Strength, Stories of Survival

The study did not stop at altitude adaptation. Researchers also identified genetic variants linked to metabolism, immune response, and physical activity—traits that could have played critical roles in surviving not only thin air, but freezing temperatures, nutritional scarcity, and rugged terrain.

These adaptations were found across populations living at different altitudes, hinting at an intertwined web of genetic inheritance, cultural resilience, and environmental shaping that has unfolded over millennia.

From a scientific standpoint, this fills a glaring gap in the global genetic map.

“This work fills a major gap in our understanding of human genetic diversity,” said co-author Yali Xue from the Wellcome Sanger Institute. “It highlights the importance of inclusive research that reflects the full range of global populations.”

The significance of this cannot be overstated. For too long, genetic research has focused disproportionately on populations of European descent. By studying underrepresented and often isolated groups like those in the Himalayas, researchers can uncover biological insights that would be impossible to glean from studying urban, lowland populations alone.

A Legacy Written in DNA—and in Stone

Long before modern climbers planted flags atop Everest or photographers captured the majestic spires of the Annapurna range, human footprints pressed into Himalayan soil. This new study suggests that these were not fleeting visits. They were the first steps of lasting survival—proof that long before we built cities or wrote history, we were adapting, evolving, and enduring in places thought inhospitable to human life.

The fact that population divergence began more than 10,000 years ago, well before the archaeological record suggests permanent habitation, opens a new window into prehistoric human behavior. It suggests that our ancestors may have been exploring, seasonally migrating, or even settling in high-altitude regions far earlier than anyone suspected.

The mountains, it seems, have always called to us—and we have answered with resilience written in our DNA.

What’s Next: Genes and Health in a Changing World

The research team now plans to deepen their exploration, not just of the past, but of what these genetic adaptations mean for the present and future.

Could these unique genetic traits influence disease susceptibility, endurance, or metabolism in modern Himalayan communities? Could understanding these ancient adaptations unlock new treatments for conditions like hypoxia, cardiovascular disease, or even certain immune disorders?

As climate change reshapes ecosystems and exposes communities to new environmental stressors, the resilience encoded in Himalayan DNA could offer valuable lessons for human health and survival worldwide.

This is more than a study of ancient migrations—it is a story of human adaptability, a chronicle of genetic endurance, and a celebration of the hidden strength carried quietly through generations.

In the end, the Himalayas are not just a geological marvel or a spiritual refuge. They are a living archive of human evolution—etched in stone, sung in story, and now, decoded in our very genes.

Reference: Whole-genome sequences provide insights into the formation and adaptation of human populations in the Himalayas, Current Biology (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.06.048. www.cell.com/current-biology/f … 0960-9822(25)00808-5