In the arid heartlands where the Nile sweeps through northern Sudan, lies the once-proud city of Dongola—a capital of lost kingdoms and the silent witness to centuries of civilizational change. For centuries, the story of this ancient metropolis rested in the sands of time, buried beneath layers of conquest, cultural transformation, and neglect. But now, thanks to a remarkable reexamination of a forgotten manuscript, a long-lost voice has emerged—clear, eloquent, and resonant.

This voice belongs to Takla ‘Alfā, a 16th-century Ethiopian monk, whose journey to Dongola and spiritual reflections offer a stunning first-hand account of a medieval African city on the cusp of irreversible transformation. His words, preserved in a colophon once locked away in the vaults of the Vatican Library, are not merely devotional utterances. They are historical gold. And now, thanks to the groundbreaking work of researchers Dr. Dorota Dzierzbicka and Dr. Daria Elagina, this rare document is casting new light on a pivotal moment in African history.

Published in the journal Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa, their study is part revelation, part detective story, and wholly revolutionary.

A Manuscript Hidden in Plain Sight

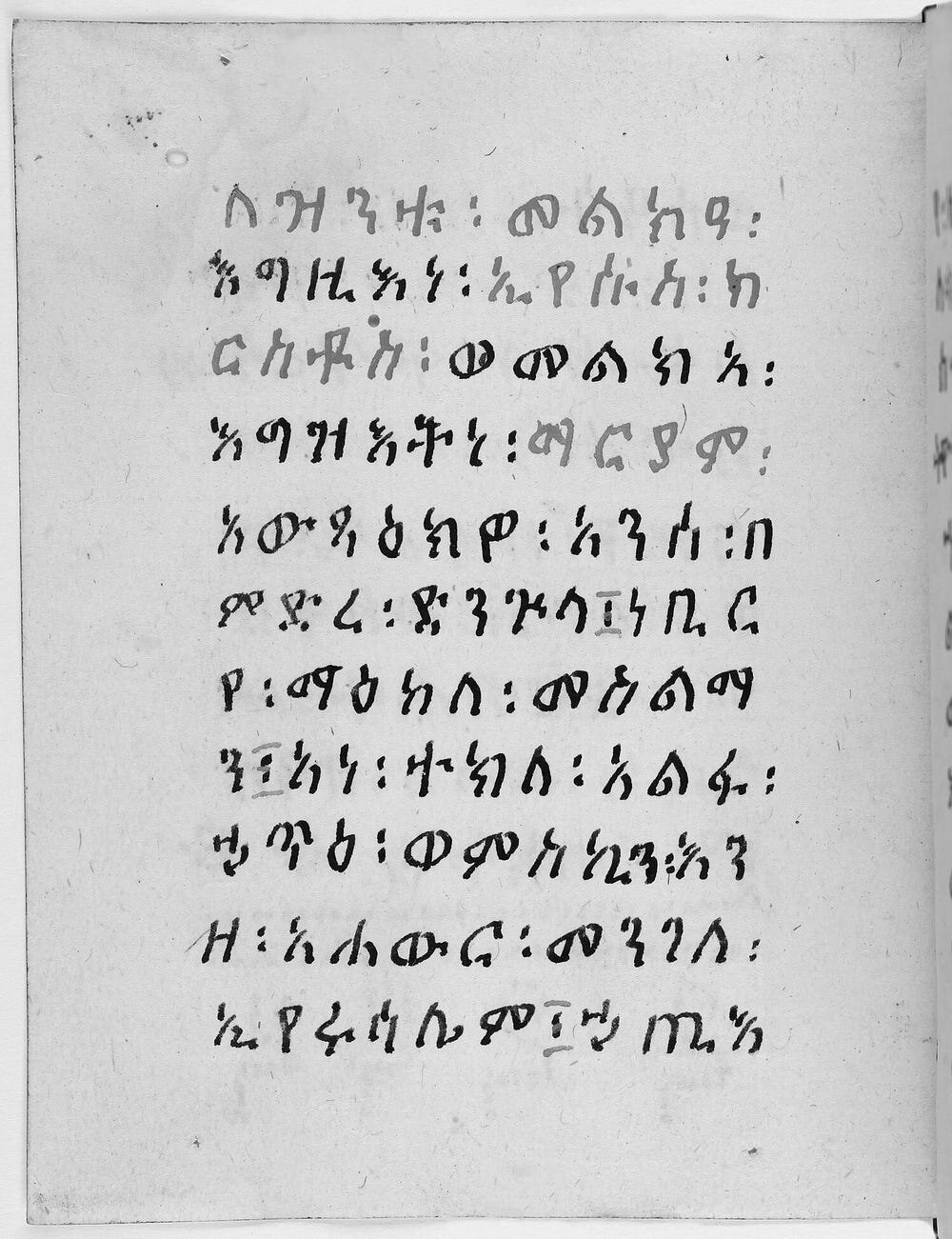

Takla ‘Alfā’s account, nestled at the end of a collection of hymns in the ancient Ethiopic script of Ge’ez, had long been misunderstood. Transcribed and translated into Latin in the 1930s, the manuscript was academic fodder for a few niche scholars—linguists, mostly—who saw it as little more than a liturgical curiosity. But in truth, it was a lantern cast into the murky depths of 16th-century Nubia.

It wasn’t until the 1990s that Ceccarelli-Morolli flagged the document’s importance to Nubian studies, noting its unique references to the Islamization of Dongola. Even then, the full richness of the text lay buried beneath centuries of scholarly compartmentalization. Nubian historians, trained in Greek, Coptic, Old Nubian, or Arabic, often overlooked texts in Ge’ez, while Ethiopianists dismissed a narrative set far outside the Ethiopian Highlands.

“It’s no surprise the colophon’s significance for economic and social history has largely gone unnoticed,” explain Dr. Dzierzbicka and Dr. Elagina. “It fell between disciplinary cracks—too Nubian for Ethiopianists and too Ethiopian for Nubianists.”

But they saw what others had missed: a remarkable travelogue, a cross-cultural memoir, and a social commentary all bound into one slim passage at the end of a religious manuscript. Takla ‘Alfā was no mere pilgrim; he was a chronicler of a vanishing world.

Faith and Observation: Takla ‘Alfā’s Hymns and Testimony

At first glance, the colophon appears unremarkable—just a modest closing note following a series of devotional poems, or malkǝ’, addressed to Christ and the Virgin Mary. But nestled in this closing flourish are Takla ‘Alfā’s observations during his stay in Dongola, dated to 1596.

He records that the city was already fully Islamized—a claim that contradicts earlier academic assumptions that Islam gradually took hold in Dongola over the 17th century. According to the monk, by the late 16th century, Christian practices had vanished. Pigs, once common in the Christian Makurian diet, had disappeared. Arabic was the dominant script. And all signs pointed to a society ruled and reshaped by Islam.

In his brief but poignant notes, Takla ‘Alfā does not describe persecution or violence. Instead, he paints a picture of a city that had already been enveloped by Islamic culture, while retaining its importance as a bustling urban hub. His journey—from Ethiopia, through Dongola, and onward toward Jerusalem—follows ancient trade arteries that reveal the city’s persistent strategic and economic relevance.

Archaeology Meets Ancient Testimony

For decades, the story of Dongola’s Islamization was constructed largely from material remains—artifacts, architecture, and burial customs. Much of that story is being reinterpreted by the ERC-funded UMMA project (Urban Metamorphosis of the community of a Medieval African capital city), led by Artur Obłuski and conducted between 2018 and 2024 by the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw.

The UMMA team excavated layers of domestic life that hint at significant social shifts. They found humble domestic assemblages—pottery, tools, and ordinary household items—suggesting a broadly egalitarian society. Yet one structure loomed large: the House of the Mekk, or king, stood out as a residence of clear elite privilege. Within its walls, archaeologists discovered a treasure trove: silk fabrics, coins, musket balls, and documents written in Arabic.

One particularly tantalizing document bore the name of a king of Dongola—Qashqash or Qushqush—attesting to the extent to which Islamic identity and Arabic literacy had been woven into the political fabric of the elite. Takla ‘Alfā’s written reflections dovetail precisely with these findings. Where the archaeologists unearthed traces of transition, the monk recorded its lived reality.

The “Gelaba” Merchants: Forgotten Pioneers of Trade

Perhaps the most electrifying discovery in Takla ‘Alfā’s text is the earliest known reference to the “gelaba”—a class of long-distance traders who would later dominate trans-Saharan and trans-Nilotic commerce.

The word gelaba, borrowed from Arabic, refers to traveling merchants whose camel caravans stitched together the distant lands of Egypt, Sudan, and Chad. Their appearance in the monk’s 1596 account pushes the recorded history of this group back by over a hundred years, revealing that their commercial networks were already active, sophisticated, and vital to regional economies.

“These traders were often thought to have emerged prominently in the 17th and 18th centuries,” explain the researchers. “But Takla ‘Alfā’s mention proves that they were not only present but socially significant in the 16th century.”

Their role as agents of exchange helps explain the foreign goods found in Dongola—from Egyptian ceramics to Levantine glassware. The city’s markets, enriched by gelaba trade routes, were vibrant with the echoes of far-off lands.

From Ethiopia to Jerusalem: A Continental Pilgrimage

Takla ‘Alfā’s journey was not random. It followed ancient rhythms of pilgrimage and commerce that connected Christian Ethiopia with the Holy Land through Nubia and Egypt. His colophon testifies not only to his personal piety but to the enduring geographic and spiritual ties that knit together African Christianities with broader transcontinental routes.

Even as Dongola itself shifted from Christian Makuria to an Islamic city, it remained a vital artery in this sacred geography. Pilgrims like Takla ‘Alfā continued to pass through its gates—travelers, yes, but also witnesses.

What makes Takla ‘Alfā’s account so profound is that it does not mourn the loss of Christianity in Dongola. Instead, it quietly acknowledges change, resilience, and continuity. Though the city’s cathedrals had become mosques, its roads still hummed with life, its houses still hosted strangers, and its markets still carried whispers from across the desert sands.

A City Remembered, A History Rewritten

The recovery of Takla ‘Alfā’s narrative is more than an academic footnote. It is a reclamation of voice and perspective, a shift in the center of gravity of how we understand African history.

It shows us that Dongola did not vanish with the decline of Makuria. Instead, it metamorphosed—religiously, economically, socially. And it did so not in a vacuum, but in concert with broader transregional currents that connected the Christian highlands of Ethiopia to the Islamic north and beyond.

Through the combined efforts of historians, archaeologists, and linguists, the story of Dongola is being rewritten in vibrant, human detail. In this rewriting, Takla ‘Alfā takes his rightful place—not just as a monk and pilgrim, but as a chronicler of his time, bridging the worlds of faith, commerce, and empire.

Echoes Through Time

The final lines of Takla ‘Alfā’s colophon might be liturgical, but their true power lies in what they reveal beyond the hymn. They speak to us across centuries—not as dogma or doctrine, but as observation and memory.

Thanks to the efforts of Dr. Dzierzbicka and Dr. Elagina, this remarkable text no longer languishes in obscurity. It now stands as a beacon, illuminating a shadowy corner of African history with clarity and warmth.

In the interplay of archaeology and ancient testimony, Dongola is not merely unearthed—it is reawakened.

Reference: Dorota Dzierzbicka et al, “I resided in Dongola, amongst the Nubians and Muslims, on my own.” The sixteenth-century account of Ethiopian monk Takla ‘Alfā in context, Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa (2025). DOI: 10.1080/0067270X.2025.2477380